European Community law in Denmark, 1973-1993

When Denmark became a member of the European Community in 1973, European law was not high on its domestic agenda. It was first and foremost the potential economic benefits of membership that occupied the public consciousness. However, European Community law went on to have explicit consequences for Denmark, but it was not until the late 1980s that it was first clear what it would mean; Law emanating from the European Community’s key institutions constituted rules and regulations of major importance to the member states, including Denmark. It gave member states, private companies and citizens rights and obligations, and these rules and regulations became part of the member states’ legal systems. After 1st November 1993, it became EU law.

European law’s development

It was not clear from the outset that the legal framework of the European Community would play such an important role in cooperation as it went on to do. In the 1957 Treaty of Rome regarding the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the European Court of Justice was actually weak. However, the extended scope of areas of cooperation within the community led to a greater role for the European Court of Justice, and it was given sole authority to interpret community law. It was these changes that made it possible for the European Court of Justice to take on a more central role. The argument for this was that, if an actual common market was what was wanted, legal security for economic actors was absolutely necessary. With this focus on the treaty’s key aim of establishing a common market, the Court was secured a more central position. In the first half of 1960s, the European Court of Justice with two essential rulings was successful in establishing the core principles of 'direct effect' and precedence of community law over national law. The European legal system continued to be dependent on cooperation with the national courts, but, from a European law perspective, clear lines had been established on who had the final authority.

In spite of the member countries accepting the principles of direct effect and European law’s precedence, the national courts and legal systems in a number of cases have opposed the European rules. In particular, there has been a number of countries that have made reservations from these principles with respect to their constitutions, and the national administrations have in many cases tried to work around - or even been in direct opposition - to decisions of the European Court of Justice.

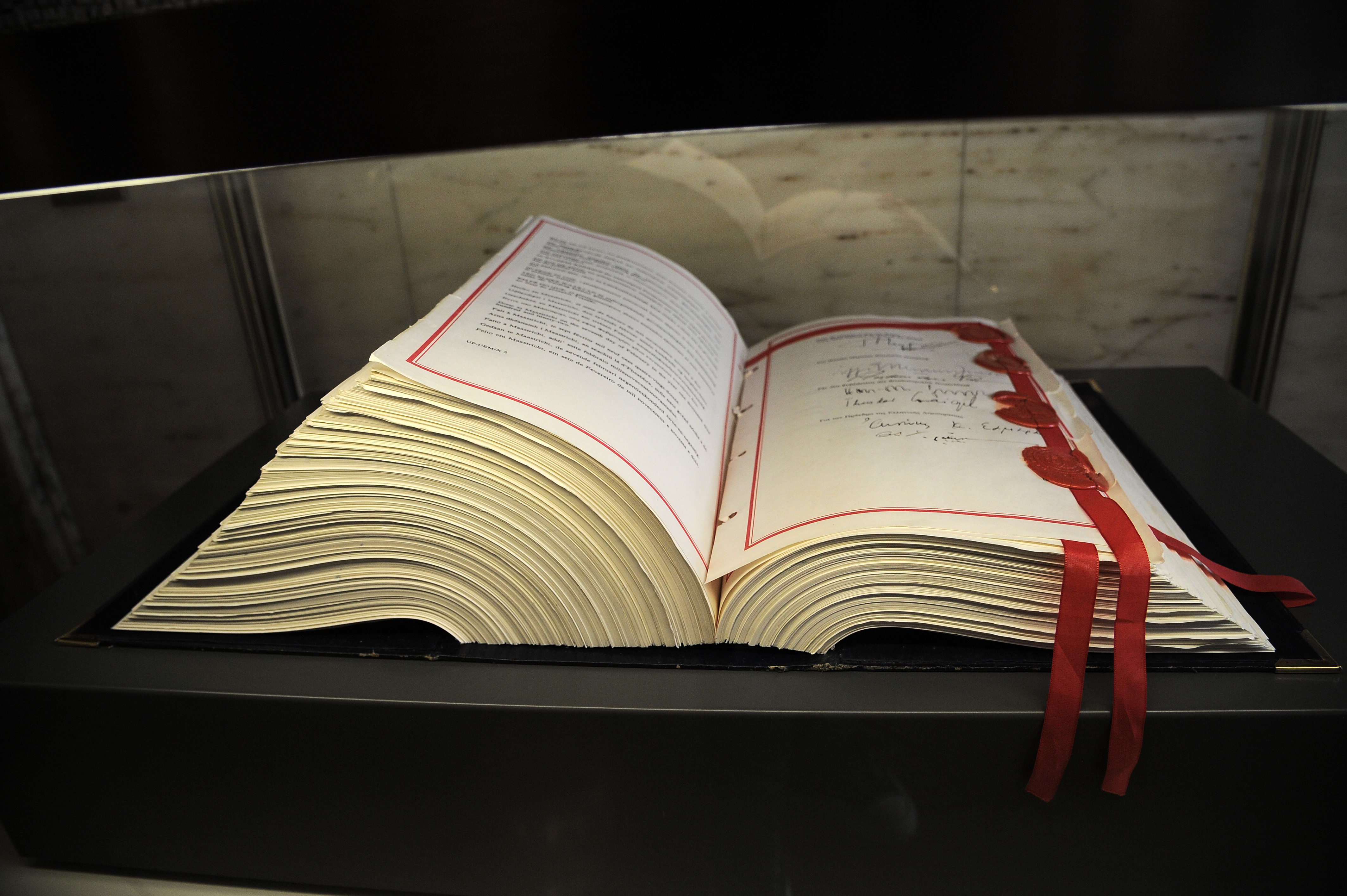

PICTURE: The signing of what is often referred to as the ‘Treaty of Rome’ which established the European Economic Community on 25th March 1957 in Palazzo der Convervatori in Rome. Seated from left to right are: French Foreign Undersecretary Maurice Faure, German Chancellor Konrad adenauer, German Foreign Affairs Underseretary Walter Hallstein, Italian Premier Antonio Segni and Italian Foreign Minister Gaetano Martino. Photo: EC - Audiovisual Service.

The legal basis for Denmark’s membership of the European Community in 1973

From the Danish side, becoming a member state demanded a great deal of adaptation. One significant challenge was to create a legal construction that ensured that the Danish membership did not conflict with the Danish constitution. Already in the 1960s, there had been a discussion among prominent law professors about whether Section 20 of the Danish constitution provided a sufficient legal basis for Denmark to accede to the EEC without a constitutional amendment. The section was written into the Danish constitution in 1953 and was intended to create a legal basis for the Danish state to delegate sovereignty to supranational institutions such as the EEC. The result of the debate was that the Ministry of Justice prepared a report that dealt with the potential legal problems that could arise if Denmark became a member of the European Community. The fundamental premise in the Ministry of Justice’s argument was that European Community law did not differ significantly from traditional international law. With regard to the primacy of community law, the Ministry of Justice argued that it was not necessary to safeguard this principle in the Danish constitution. They said that the legal system in Denmark allowed the parliament, the administrative authorities and the courts to respect the principle in all cases where the parliament did not legislate with the specific intention of violating community law. The consequence of that argument was that Denmark negotiated a reservation to community law by preserving ultimate judicial authority over the Danish system.

The Luxembourg Compromise 1966

Another central aspect of the Danish understanding of European Community law’s consequences was based on the Luxembourg Compromise. On 28th January 1966, the six original European Community countries (Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Italy, Luxembourg and West Germany) reached an agreement regarding how they would be able to continue cooperation. Prior to this, there had been a dramatic build-up where France had boycotted the European Community’s institutions for half a year. France had demanded that the principle of unanimity in the Council of Ministers be strengthened, while the other countries were more open to making it weaker. The compromise was that, when vital national interests were at play, the Council of Ministers would endeavour to reach a agreement that would be agreeable to all member states. France insisted, however, that when such interests were at play, the negotiations should continue until a unanimous agreement was reached. This meant that what in reality was a veto was introduced which the member states were able to use at the Council of Ministers. The compromise led Danish legal experts to conclude that, when Danish sovereignty or vital interests required it, Denmark would be able to block new initiatives at the Council of Ministers. In this way, legal experts in the Danish ministries were able to construct an argument which meant that the principles of primacy and direct effect of European law in Denmark did not formally threaten Danish sovereignty.

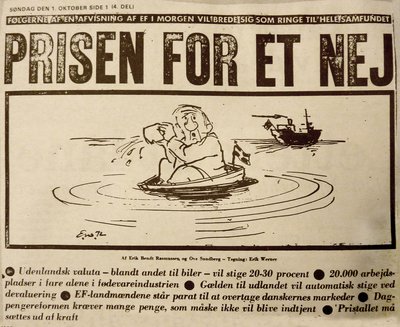

PICTURE: 'The price for a no' - A cartoon from the newspaper Berlingske Tidende from 1st October 1972. The picture was a part of the election campaign in connection with the European Community referendum on 2nd October 1972.

Three phases in Denmark adapting to European Community law

When Denmark on 1st January 1973 became a member of the European Community, an overwhelming task awaited Danish civil servants. It was a condition of membership that Denmark implemented all European Community legislation. At the same time, the European Community was a dynamic cooperation that continually developed and new laws were being produced all the time - judgments and rules that Denmark was supposed to adapt to. The implementation of European Community law was in fact relatively unproblematic, but it was in relation to the subsequent interpretation and development of European Community law where problematic issues would occur.

PICTURE: Max Sørensen – the first Danish judge for the European Community court where he sat from 1973 to 1979. Photo: Nationaal Archieef, Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0

The establishment of the Special Legal Committee in Denmark

The first years of Danish membership were to a large extent characterised by a transition process. In the administrative system, a practice was established where the individual ministries were responsible for dealing with EC law in their respective areas. Already during the course of 1973 it became clear that there was a need for a central body that was able to assist the ministries in understanding and interpreting community law issues. The Special Legal Committee was therefore established in June 1973. The committee brought together the European legal expertise within the Danish civil service in one and the same body. The committee came to play a particularly defining role in how the Danish state handled EC law administratively, legally and politically.

The Danish courts did not immediately begin to use European law and make use of the possibility of sending questions on particular points of law to the European Court of Justice; it was the duty of Danish courts to refer cases to the European court when a question of interpretation of EEC law arose. The Danish court ignored this process, and it was not until the end of 1970s that the first Danish cases were in fact referred to the court.

Denmark’s first case at the European Court of Justice

In 1977, the first case came before the European Court of Justice where the Danish state was the defendant. The case concerned two goldsmiths who complained about the relevant public authority’s control over precious metals. The Danish civil service had not been aware of the case and were therefore surprised when the complaint arrived from the European Court. Even though the European Court recognised local Danish practice and did not support the two goldsmiths, the decision itself was potentially problematic for Denmark as it contained an extended understanding of European treaties.

The case meant that the Special Legal Committee began to adopt a far more controlling approach. By involving individual ministers, the public prosecutor, government lawyers and judges, the committee established a system where it was informed at an earlier stage about potential cases that could end up at the European Court. At the same time, a screening process was established which involved the committee evaluating which cases were suitable to be sent to the European Court of Justice and how the questions should be formulated to the court.

It was generally characteristic of the period that civil servants played a dominant role in how the European Court of Justice was seen and dealt with in Denmark. The politicians, on the other hand, kept their distance from the legal aspects of European Community cooperation. Danish civil servants had successfully created a system that shielded the politicians from being involved.

European law in Denmark in 1980s

After 1980, the system which Danish civil servants had established to control the European Court gradually broke down. This led to politicians being confronted with the consequences of European law to a larger degree and meant that they had to formulate concrete policies in the area. The European Court of Justice was especially politicised in Denmark because the European Commission had started to take an increasing number of cases against the country. Additionally, there was a rising dissatisfaction with the court’s activist practice among the member states, a feeling which was also reflected in the Danish debate.

In the Danish administrative system, there was significant dissatisfaction with the European Court. It was accused of being activist, unpredictable and its actions unacceptable. Despite this, Danish civil servants and politicians were not prepared to join the backlash against the European Court that began around 1980. Consideration for securing a firm foundation for European Community cooperation based on law and rules that were strong enough to control even the larger members states still held more weight.

The Single European Act in 1986 and the agreement to expand the single market meant that more and more European legislation became relevant to Denmark. These developments meant also that ordinary citizens in the European Community, including Denmark, began to experience concrete advantages in their daily lives. The removal of barriers to trade meant that restrictions at borders were phased out, so private individuals could, for example, import more alcohol without having to pay extra duty. It was also easier to look for work in other European Community countries.

In addition to this, at the end of 1980s, there was a large focus on the rights and opportunities that European cooperation gave people as well as firms. Despite this, the Danish state supported a practice where it attempted to bypass European Community obligations where possible. This practice was a continuation of how European law had first been understood and used in Denmark in the initial 15 years of membership. Denmark wanted, first and foremost, a legal community which was obligatory and that enforced and respected the common rules, but, when it came to Danish economic and political interests in particular, Danish officials and politicians were very creative in circumventing the consequences of community law.

Further reading:

- Bill Davies, Resisting the European Court of Justice (Cambridge University Press; 2012).

- Claus Gulmann, ‘The Position of International Law Within The Danish Legal Order’, The Nordic Journal of International Law, 52, 3-4 1983.

- Henrik Zahle, EU og Dansk Statsforfatningsret [EU and Danish Constitutional Law] (2002).

- Jonas Langeland Pedersen, Constructive Defiance? Denmark and the Effects of European Law, 1973-1993 (2016).

- Morten Rasmussen, ‘Constructing and Deconstructing “Constitutional” European Law, in Henning Koch, Karsten Hagel-Sørensen, Ulrich Haltern, Joseph H. H. Weiler, The New Legal Realism: Essays in Honour of Hjalte Rasmussen. (Djøf Forlag, 2010) pp. 639-660.

Thanks go to danmarkshistorien.dk for allowing us to translate this article. Read the article in Danish here