The emergence of Norwegian civil society in the 19th century

Voluntary organisations were a new and important phenomenon in Norway in the nineteenth century and included many different types of associations, unions and clubs. Among other things, they functioned as places to learn about democracy for the wider population.

What kind of organisations were there?

In Norway, there was an upsurge of people organising themselves into associations of different types in and around 1840. This is referred to now as ‘Assosiationsaanden’ (the spirit of associations – or an eagerness to form associations). Some groups had existed earlier in the shape of parish societies, reading associations and private clubs. After 1840, the number of associations grew from very few to several thousand within a few generations. Many of them started out as local associations which eventually grew into nationwide phenomena. Ten national associations in 1850 had by 1900 grown to 154, most of these with headquarters in the capital. The associations came in many different variations:

- Political organisations, like the Thrane-movement, the farmer associations, and eventually political parties.

- Organisations centred on particular professions, including artisan associations. From the 1870s, more explicit interest organisations emerged, including trade unions, organisations for many of the different professions and eventually employers’ organisations as well.

- Economic organisations, like savings banks, aid funds, production cooperatives (dairies, for example) and consumer cooperatives.

- Cultural and educational societies, such as reading associations. Examples include Selskabet til Folkeoplysningens Fremme (Society for the Promotion of Public Knowledge), Den Norske Turistforening (The Norwegian Trekking Association) and Fortidsminneforeningen (Society for the Preservation of Ancient Norwegian Monuments).

- Missionary associations, which were in fact among some of the first of the movement. These were initially concerned with missionary activities abroad, but they later turned their focus towards domestic missionary activities as well.

- Philanthropic associations, which aimed to combat poverty, lack of housing and immorality.

- Social associations, which included clubs exclusively dedicated to social activities.

Many organisations belonged to more than one of these categories, and they could have political, economic and cultural aims at the same time.

PICTURE: As industrial conflict escalated in the 1890s, separate marches were organised to celebrate May 17th, Norway’s Constitution Day. Pictured here is the ‘Apolitical Associations May 17th March’ at Hamar in 1895. Numerous associations including the Temperance Society, the Artisan Associations, Hamar’s Trading Association, the Gymnastics Association and Hamar’s Youth Society all participated. Two years later in Lillehammer, a similarly ‘apolitical’ march took place: the ‘apolitical Højre-march’. There was also a Venstre-march, with the workers’ union, tailors and typographers marching alongside each other. Photo: Domkirkeoddens Photo Archive.

Why did all these organisations emerge at the same time?

All the organisations that were founded had one or more specific objective, such as furthering the interests of one specific group (unions), contributing to society’s greater good (cultural or temperance), or bringing people together in a social context (all organisations). The Norwegian state had a limited reach and could not fulfill all these ambitions. Many of the associations also functioned as pressure groups towards the state.

The great social upheavals of the 19th century meant that traditional ties between family, neighbour and professional were weakened and had to be replaced by others. The organisations became important social arenas for many Norwegians. The general improvement in writing and reading skills among the wider population also contributed to the growing ‘organisational society’.

The Norwegian Constitution’s emphasis on freedom of the press was another important factor which gradually evolved into both organisational freedom and freedom of speech, especially after the middle of the century.

Who were the members of these societies?

The members of these organisations and societies were diverse. In the first phase, state officials were often both initiators and leaders, but later on, farmers and the city-based middle class, in some cases also workers, took the lead. Missionary associations, temperance associations, trade unions and many professional associations were dominated by common people, whereas cultural and philanthropic associations were more bourgeois.

The involvement of women, and in some cases even female leadership, was an important element in many of the associations. This was especially the case in terms of temperance and missionary activities, but also within culture, philanthropy and some professional associations.

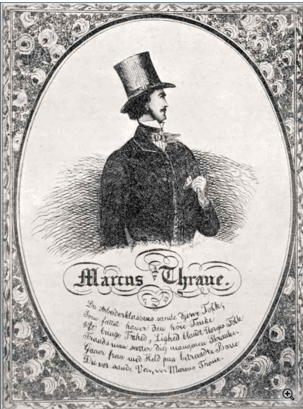

PICTURE: Around 1850, Marcus Thrane led the so-called 'Thrane movement' which was the first political mass movement in Norway. He is regarded as the first Norwegan socialist. Photo: Norsk Biografisk Leksikon.

The importance of the civil society movement in Norway

The blossoming of these organisations - civil society as it would later be called - was of vital importance to the development of Norwegian society in the nineteenth century.

The organisations constituted an important link between the authorities and residents, as people managed to organise and express their economic and political interests at a time of limited public involvement.

The organisations also became important schools for democracy. They were usually built on democratic principles, with elections to the board and equality for all participants, while at the same time helping to further reading and writing skills. Helped along by the development of the press, these organisations managed to expand the Norwegian public sphere as well as freedom of speech. At the same time, the national organisations connected people from different regions together, uniting them over common causes.

Further reading:

- Inger Furseth, People, Faith, and Transition. A Comparative Study of Social and Religious Movements in Norway, 1780s-1905 (Oslo: University of Oslo, 1999).

- Johan Raaum, 'De frivillige organisasjonenes framvekst og utvikling i Norge' [The emergence and development of voluntary organizations in Norway], Frivillige organisasjoner NOU 1988, 17 (Oslo, 1988) pp.239-355.

Links:

- Thanks go to norgeshistorie.no for allowing us to translate this article. The original article can be read in Norwegian here.