The German Minority in Southern Denmark

The historical duchy of Schleswig was divided following two plebiscites in 1920. Ever since, South Schleswig has formed the northern section of the German federal state of Schleswig-Holstein, whereas North Schleswig forms the Danish border region of South Jutland. National minorities were left behind on both sides of the border. Thus, a minority of people who live in southern Denmark identify as German, and a minority of German nationals south of the border identify as Danish. History helps to explain how identity transgresses national boundaries in the region.

The Duchy of Schleswig: A link between two cultural spheres

For many centuries, the duchy of Schleswig connected the German and Scandinavian worlds. The duchy originated within the Danish realm. Yet by the late Middle Ages, it had become closely intertwined with the neighbouring German principality of Holstein. In 1460, the Danish king assumed power over both territories, but recognised their special constitutional status and interconnection. In subsequent centuries, they were substantively treated as the German duchies of the Danish conglomerate state.

This dual affiliation also expressed itself on a cultural level. The rural majority spoke Frisian along the southwestern coast, German in a growing segment of the southeast, and Danish in the northern half of the duchy. Language use in the urban centers of the north showed greater bilingualism, since German was the predominant language of education and administration.

Prior to the ascent of nationalism, this cultural diversity did not cause many tensions. In the nineteenth century, however, Schleswig became the center of a drawn-out conflict. The Schleswig-Holstein movement saw the duchies as a coherent, German-dominated whole, which was to be treated as a self-governing entity on equal footing with and with limited ties to the Danish kingdom. For the Eiderdane movement, in contrast, Schleswig formed a natural constituent of the Danish kingdom, in which it was also to be included constitutionally.

A German uprising in Schleswig and Holstein was defeated in the middle of the century (1848-1850), but fundamental disagreements about the duchies' political future remained. When Denmark attempted to implement Eiderdane conceptions, the German powers intervened militarily and won a decisive victory in 1864. The duchies were detached from the Danish crown. Between 1867 and 1920, Schleswig-Holstein was a province of Prussia and thus, from 1871, also of the newly founded German Empire.

The origins of a German minority in North Schleswig

In the early 1800s, nationalism primarily reached Holstein and southern Schleswig in the form of a German-oriented Schleswig-Holsteinism. Most Danish-speakers in northern Schleswig, in contrast, gradually expanded their localised cultural attachment into a more encompassing Danish national identity. This transformation was not shared by all segments of the population. Towns and cities had long contained a substantial German element. Some of its members hailed from the southern half of the duchies or the German heartland. Others had been born in Danish-speaking regions but had been drawn into the German cultural sphere through higher education and professional advancement.

Not even in the more uniformly Danish-speaking rural districts did everyone share the goals and aspirations of the Danish national movement. The special legal and social conditions in the duchies formed central markers of identity. Thus, the origins of German identity in North Schleswig were typically rooted in a Schleswig regional identity. This identity upheld the traditional order, in which the two duchies of Schleswig and Holstein formed an independent entity that coexisted with the kingdom, albeit under the common roof of the composite monarchy. Both the new German Schleswig-Holsteinism in the south and the new Danish national movement in the north strove to supplant this traditional order. Those who remained attached to it found themselves in opposition to the locally prevailing faction. In Flensburg, many German speakers were loyal to the monarchy and supported the Danish cause. In some regions of northern Schleswig, Danish speakers upheld the duchy's autonomy and self-sufficiency and became the foundation of a German community.

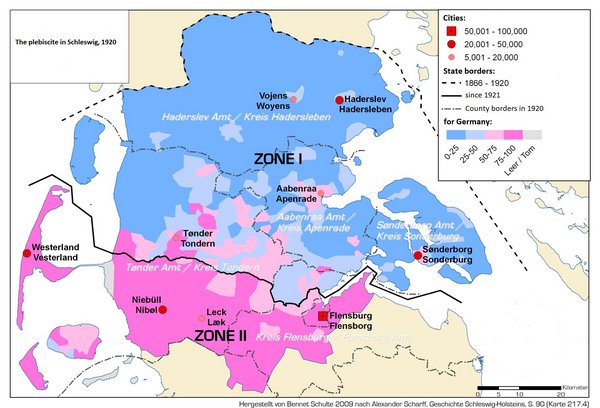

During the Prussian period between 1867 and 1920, the German-minded population throughout the duchies enjoyed the benefits of majority affiliation. The German defeat in World War I, however, put the Schleswig question back on the table of European politics. Articles 109-114 of the Treaty of Versailles provided for separate plebiscites in northern and central Schleswig. On 10 February 1920, almost 75% of the voters in the northern zone supported incorporation into Denmark. Since the whole northern zone was treated as one, substantial German minorities in select border districts had no effect. After approximately 80% of the voters in zone 2 subsequently had opted for Germany, the international powers divided Schleswig along the line of demarcation between the two zones.

Following the peace settlement of World War I, the unified history of Schleswig had come to an end. After many centuries as a multiethnic link between different cultural spheres, the old duchy had been torn asunder by modern concepts of nationalism. Nonetheless, the ties were not completely broken. Schleswig history was also henceforth not just ordinary German and Danish history, because there were people on both sides of the border whose self-identification transgressed the political divide.

Map showing distribution of the German vote in the plebiscites of 1920. Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

The German minority in Denmark since 1920

Since the current political border was established in 1920, both the German minority in Denmark and the Danish minority in Germany have experienced substantial fluctuations in numbers. These fluctuations have often mirrored the political and economic fortunes of the respective nation-states and are rooted in the specific character of both minorities as subjective or identificational minorities. Membership is not based primarily on cultural markers such as language, but on self-identification with the minority. Most minority members do not use a minority language as their foremost medium of communication. Combined with the lack of official ethnic censuses, this specific character of minority affiliation makes it difficult to establish its exact size. Estimates are based on election results and on the participation in the social, cultural, and political infrastructure of the minority.

While Germany garnered a quarter of the votes in the plebiscite, approximately 15% of the North Schleswig population identified with the German minority in the interwar period, and only six to eight percent do now. Thus, the German minority in Denmark is noticeably weaker today than it was in 1920. After an initial reduction in number, caused especially by the movement of former German civil servants to the Weimar republic, the minority managed to consolidate and to build up a sound cultural and political infrastructure. The far-spread cooperation with the German occupation authorities between 1940 and 1945, which partially echoed the Danish government’s ambivalent policy but also reflected the minority’s political orientation toward Germany, isolated and subsequently endangered the minority. Many of its members were sentenced for collaboration after the war, and most of the minority’s schools were confiscated. Although these measures weakened the minority numerically and impacted its educational resources, they also reinforced the national divide and thus the separate identity of the minority’s core membership.

The Crown Prince and Princess of Denmark on an official visit to the German minority in North Schleswig, 2008. Photo: Courtesy of nordschleswig.dk.

The gradual reduction in border activism and wartime antagonism, which expressed itself not least in the Bonn-Copenhagen Declarations of 1955 that provided for minority protections on both sides of the border, led to a gradual reintegration of the German minority into the region’s public life. With the assistance of both the Danish and German governments, the minority was able to rebuild its organisational structure. This normalisation of ethnic relations has not been without problems for the minority, however, as younger generations of German North Schleswigers are increasingly defining their German identity as only one element of a wider South Jutland (sønderjysk) identity. Thus, the German minority in Denmark, which derives its origins predominantly from a sense of self and not from visible cultural markers, faces the continuous challenge of imparting this sense of self to new generations that are widely integrated into the larger Danish society.

Further reading:

- Jürgen Zeh, Die deutsche Sprachgemeinschaft in Nordschleswig: Ein soziales Gebilde im Wandel [The German Language Community in North Schleswig: A Social Entity under Transformation] (Stuttgart: Ferdinand Enke Verlag, 1982).

- Jørgen Kühl, ed., En europæisk model? Nationale mindretal i det dansk-tyske grænseland 1945-2000 [A European Model? National Minorities in the Danish-German Borderlands 1945-2000]. (Aabenraa: Institut for grænseregionsforskning, 2002).

- Peter Thaler, Of Mind and Matter: The Duality of National Identity in the German-Danish Borderlands (West Lafayette, Ind.: Purdue University Press, 2009).