American Attempts at Northern Expansion in the 19th Century

Revisiting imperialist incursions in Canada in the light of America’s renewed interest in Arctic resources and territories

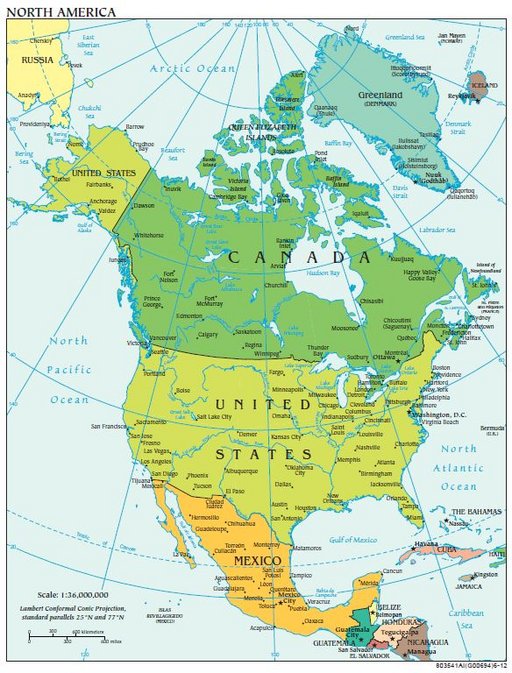

Summary: In the 19th century, the United States’ expansionist appetite turned north as well as west, although less successfully. With the exception of the purchase of Alaska, the young United States was met with internal and external opposition and attempts at northern expansion failed. Politically, these forays fitted less neatly into the ideological mold of a nation built on revolution and anti-colonial struggle. They involved dealing with other empires through either war, treaty, or purchases, and give food for thought today given America’s current posturing over Canada and Greenland.

American westward and northward expansion viewed differently

Westward expansion is widely mythologized in American culture. Spanning the 19th century, this period marks the gradual incorporation of the western part of the North American continent into the political structures of the American republic. 19th century politicians, popular culture entertainers like Buffalo Bill, and even scholars, like Frederick Jackson Turner, presented the American West as empty of human occupation and therefore a resource handed by Providence to the U.S., an ideological sleight of hand which symbolically erased the presence of Indigenous populations from the story, and avoided parallels with colonialism and imperialism. Framed by the rhetoric of American Exceptionalism, the American national ideology which presents the US as fundamentally different from, and superior to, Europe, the settling of the American West became a ‘natural’ process. In the American interpretation, Europe created empires and subjugated Native populations; the U.S. simply ‘grew.’

The story of the country’s expansionist attempts to the north is less present in the American imaginary, presumably because, with the exception of the purchase of Alaska, they were met with internal and external opposition and failed. They also fit less neatly the ideological mold of a nation built on revolution and anti-colonial struggle. These forays involved dealing with other empires through either war, treaty, or purchases, but they had the same goal of acquiring more territories and resources as the romanticized winning of the West.

America’s early imperialist attempts to the north

Canada was the first target for America’s expansionist attempts to the north, due to proximity and relative demographic similarity. At the time of the American Revolution (1775-1783), British loyalists in the thirteen colonies had trekked north to the Canadian colonies, in order to remain in the British Empire. The existence of this British imperial outpost in North America was viewed by many in Washington as a threat to national security and interests. The War of 1812 saw the young republic again at war with Great Britain over maritime disputes linked to the ongoing Napoleonic wars in Europe. In 1812, Thomas Jefferson boasted to a Philadelphia newspaper that “the acquisition of Canada this year will be merely a matter of marching.” Yet, Canadians preferred their membership in the British Empire, successfully repelled the American invasion, and the war ended as a stalemate. To this day American history textbooks and popular culture discuss it as a second war of independence between the US and Britain, while Canadians remember it as a national victory against an expansionist US coveting their territory.

Between the end of the War of 1812 and the creation of the Dominion of Canada in 1867, colonial politicians occasionally toyed with the idea of joining the US, but the idea did not gain any significant popular support for many reasons. First was the allegiance to the British Crown, which was strong. Additionally, given the chaos and recurrent violence of US politics, American-style democracy and federalism were viewed with profound skepticism by Canadians who preferred the order and stability of the British system. And lastly, because of the military power of the British Empire, the US was cautious not to start a war it might not win.

Looming threat of war throughout much of the 19th century

Yet the threat of war was always there. On the East coast, debates over the border between Maine and the US were resolved by negotiation with Britain; but in the Pacific Northwest, during the 1844 US presidential elections, the Democratic Party proposed to annex the entire disputed territory stretching from the Mexican border north to the 54th parallel. Slogans like “Fifty-four Forty or Fight!” helped propelled the Democrat James Polk (1845-1849) to the presidency, who then strong-armed the British government to accept an offer which the Crown had previously rejected; the border was drawn along the 49th parallel, a decision which left many Canadians feeling betrayed by London. Polk turned his energies south and the 1846-1848 Mexican-American war marked the greatest territorial expansion in US history to date.

During the Civil War (1861-1865), territorial expansion was on hold but after the war ended, the US started to look north again. The secretary of state William Seward (1801-1872) and Senator Charles Sumner (1811-1874) claimed hundreds of millions of dollars in compensation for British support to the Confederates during the Civil War, and asked for British North America in repayment. In 1866, as the Canadian colonies deliberated their future in the British Empire, an Annexation Bill was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives which called for the admission of the colonies into the Union, should their governments want to join. The bill did not make it out of committee, but it reflected the enduring American appetite for northern expansion. A year later, Seward started negotiations with Russia, which ended with the purchase of Alaska, despite initial opposition in the US Congress and among the public, who ridiculed the project as ‘Seward’s folly.’

Limited territorial growth of the United States

One of the most enthusiastic supporters of Seward’s Alaska idea was Mississippi senator Robert J. Walker (1801-1869), another ardent imperialist. In the summer of 1867, while Seward was negotiating with Denmark over the acquisition of the Caribbean islands of St. Thomas and St. John, Walker suggested to Seward to try to acquire Greenland and Iceland as well, and ordered the United States Coast Survey to draft a report on the conditions and resources of both. Walker’s political reasons were directly related to his plan for Canada; hemmed on both sides by US-controlled territories, he argued, the absorption of British North America into the American union would have been just a matter of time, creating an American empire stretching from the Arctic to the Caribbean. The plan was poorly received by Congress, and abandoned at the time, although the purchase of the two Danish Carribbean islands was completed under a different set of circumstances decades later in 1917.

In 1869, the American President Ulysses Grant (1822-1885) suggested that Canada hold a referendum on independence from Great Britain, as a first step towards joining the United States. If nothing came of this suggestion it was mostly due to the negotiating talents of the Canadian Prime Minister John MacDonald (1815-1891). The resulting Treaty of Washington signed in 1871 settled the various disputes between Britain and the US and, crucially, it recognized the Canadian Dominion as a sovereign and legitimate political entity.

Afterwards Canada largely fell off the American radar. By contrast, Greenland’s strategic location made the island still appealing to US politicians throughout the 20th century and beyond, even as American appetite for territorial expansion was gradually replaced by a push for global military and economic supremacy. In 1947, the Truman administration secretly offered to purchase Greenland for the price of $100 million in gold. In 1960 President Eisenhower again discussed the possibility with King Frederik IX of Denmark. Each time, Denmark refused.

The narratives used to justify the territorial expansion of the United States in the 19th century – both in a westward and northward direction - are arguably very different from those used by the Trump administration, despite the continuing populist success of evoking the pioneer spirit. However, expansionist posturing with respect to Greenland in 2019 and 2024/5, and now Canada as well, evokes older 19th-century geopolitical considerations on the part of the US.

Further reading:

- Oana Godeanu-Kenworthy, Between Empire and Republic: America in the Colonial Canadian Imagination (Lexington Books, 2022).

Links:

- C. Michel, ‘Russia’s First Secret Influence Campaign: Convincing the U.S. to Buy Alaska’, in Politico on September 8, 2024.

- Oana Godeanu-Kenworthy, ‘Canada has long feared the chaos of US politics’, in The Conversation on March 8, 2022.