French Settlers in the North Atlantic

The development of the Subarctic islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon reflects Nordic history

Summary: The islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon south of Newfoundland officially became a colonial outpost of France in the early 17th century. Their extensive fishing banks led to numerous disputes between France and England over the territory, and they were a key part of the international fishing and shipping industry for much of the 19th and 20th centuries. The massive exploitation of fish reserves eventually led to a total collapse of cod stocks in 1980 and 12 years later a moratorium on fishing by Canada. While the history of the islands is not precisely the same as the Nordic north Atlantic region, there are similarities.

The islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon are found south of Newfoundland, which is south west across the Labrador Sea from Greenland. They were first occupied in the 17th century by fishermen and hunters from various provinces in France. The area amounts to 240 square kilometres in the Subarctic region. It is a two-island archipelago and has 6000 inhabitants.

While it is not so significant today, Saint-Pierre and Miquelon were in fact a key part of the international fishing industry for over 400 years until the 1990s. During much of that time, France’s maritime and polar activities all contributed to the emergence of a French-style “nordicité” (nordicity). This was largely rooted in a colonial vision, but also had a scientific and educational element; the French also learnt more about the Arctic and Subarctic, its natural and cultural ‘mysteries’ and ressources. The “North” ultimately became just as exoticized as France’s southern colonies, and in a similar way to the Arctic.

Abundant fish resources attracted early North American visitors and European settlers

Prior to the islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon first being discovered by Europeans, Northern American indigenous populations took advantage of the abundant food resources the islands offered. In the 15th or 16th century, either 1497 or 1520 depending on which sources you prefer, European settlers came to the islands, some of whom settled permanently. European ships initially visited only sporadically during the fishing season, but the archipelago very quickly became a hub for the regional fishing trade.

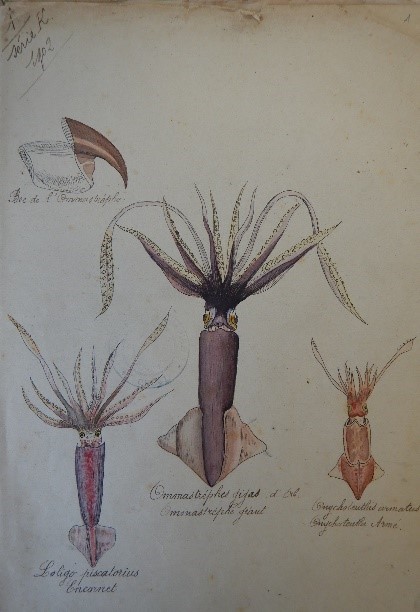

The fishing industry gradually became entirely dedicated to supplying Europe, making the coasts of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon and their bordering seas an extractive industry of incomparable scale. The large so-called ‘fishing banks’ of the region were used for cod fishing as well as numerous other types of catch: Waterfowl were hunted on the islets; salmon were caught in the estuaries; seals were killed on the pack ice; whales were hunted in the open sea; capelin and squid were caught on the coast; and, even up until today, scallops, sea cucumbers and snow crab are fished from the shallows.

French and other settlers

Early expeditions by imperial French vessels to the North Atlantic region had the dual purpose of discovery and appropriation, leading to France claiming large tracts of land including the northern coast of eastern Canada. Initially populated by French peoples coming from Normandy, Brittany and the Basque Country from around 1604, the archipelago found itself frequently the subject of dispute between France and England, as both countries were intent on monopolizing the rich fishery resources. Eventually, the ‘French shore’ became known as the coasts of Newfoundland which were allotted to the French for fishing, according to various treaties with the English and in particular the Treaty of Utrecht from 1713. Saint-Pierre and Miquelon along with Newfoundland became definitively French in 1816 at a time when France was actually losing many of its outposts, particularly around Newfoundland.

Little by little, the French adapted their management of the area to the socio-environmental context of the Arctic and Subarctic, including dealing with ice, icebergs, storms, and cold-water resources. Social aspects included the presence of indigenous populations, as well as the organisation of the particular French fleets that fished and hunted in these waters. Although distances across the sea were vast, it still proved useful to work with neighboring countries. For example, among other naval divisions, there was a joint Newfoundland and Iceland Naval Division that existed from 1765 until 1920.

Saint-Pierre and Miquelon was ultimately led by a governor from 1887, like other colonial territories. Inhabitants were dedicated to the mono-activity of fishing, the men at sea, the women and children ashore, with administrative, civil, military, and religious infrastructures organized in such a way as to fully support this lucrative industry. The gradual urbanization of the two islands, particularly in their port districts, reflected this and included factories, refrigeration facilities, saltworks on the shore, and boat builders. Each cove was occupied by French families or metropolitan national fishing companies, and organized according to local production (whaling, lobster, salmon etc).

Smaller scale artisanal fishing was also practiced by European settlers, notably through summer fishing counters established by "petits pêcheurs saint-pierrais et miquelonnais" on the French Shore. France relinquished its rights to these fishing territories in 1904 when the Entente Cordiale agreements were signed, which marked a reconciliation between France and England, although some artisanal fishermen remained on both Newfoundland as well as on Saint-Pierre and Miquelon.

Saint-Pierre and Miquelon in the 20th century

Even during the first half of the 20th century, questions about the state of exploited stocks in the area started to arise. The famous French oceanographer and ethnographer Anita Conti wrote in the 1930s that she noted an “impoverishment of fishing grounds” after a mission on the fishing banks. French fisheries research took advantage of the territory to develop and evaluate stocks, through the French Research Institute for Exploitation of the Sea (the ‘Ifremer’ station) for example. In the 1960s, tests of new wide-mouth bottom trawlers aimed at increasing tonnage were carried out at the centre.

By the end of the Second World War (1945), the tonnages landed had increased considerably through the arrival of new gigantic factory trawlers. Ships later started to come from Asia and the USSR to exploit the large fishing banks, and the archipelago was frequented by a significant number of ships flying an incredible number of flags. The last French territory in North America to this day, the archipelago was an obligatory stopover point for the ships of many French companies as well as those from Spain and Portugal. Seafarers would find a hospital, places to worship, a post office, support according to their nationality, as well as logistical infrastructure dedicated to ships and fish processing. The crews could have a well-deserved break from the harsh conditions at sea.

There is an irony in the fact that the area, its resources and its fishing practices have enabled researchers to carry out a great deal of scientific work, initially aimed at maximizing and qualifying the fishing effort, and then, little by little, warning of the overexploitation of resources, the risks of collapse, and the exploitation of fishermen and coastal communities. The archipelago was one of the first fields of research for French maritime ethnology as well as for deep-sea oceanography and fishing science. Within all three of these areas, concomitant overexploitation of both fish and men in their marine, coastal and Subarctic environments have been recognized.

It was not until the 1970s that the first serious warnings about cod appeared, and then, in 1980, the cod stock finally collapsed, eventually resulting in the Canadian Cod Moratorium of 1992. This halted all fishing activities in the northwestern Canadian coastline and sea waters including around the French deep-sea fishing as well as fishing research in the region could no longer be supported.

The continuing importance of the story of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon

The collapse of cod stocks also had a major impact on the artisanal fishing sector. Small-scale fishing continued in a much-reduced state even after the moratorium (less than 20 fishing vessels in good years). Since 2020, however, a number of new vessels in the fleet have started up, skippered by young local fishermen, and in 2024, the style of carpentry used in the traditional fishingboats (called Doris) has been recognized as intangible cultural heritage by the French Ministry of Culture.

The similarities between the history Saint-Pierre and Miquelon and the rest of the north Atlantic region seem obvious and include different types of exploitative enterprises throughout history. The archipelago is just one of many points across this region and the world affected by the unreasonable exploitation of resources by European settlers. Scientists doubt whether the cod stocks will ever recover and activities on the islands are now largely reduced to a few centred around relict outposts. This serves as a poignant reminder of overuse and exploitation of the rich Arctic and Subarctic areas so important not only to the Nordic countries but also to the environment generally.

Anthropological research can shed light on environmental changes.

This article has been published due to readers' interest in the Arctic and climate change.

Further reading:

- Aliette Geistdoerfer, ‘Ethnologie d'une culture maritime qui disparaît : Saint-Pierre et Miquelon (France).’ [Ethnology of a disappearing maritime culture: Saint-Pierre and Miquelon] Ethnologies. Identités maritimes. 12, 2 (1990), pp. 123-141.

- Barry Gaulton and Catherine Losier, ‘Recasting mobility and movement in Eastern North America: A fisheries perspective’, The Routledge Handbook of Global Historical Archaeology (2020), pp. 828-850.

- Catherine Losier, Zhe Min Liew, Mallory Champagne, and Meghann Livingston. ‘Le grand métier et la petite pêche: Archéologie des XIX e et XX e siècles à l’anse à Bertrand, Saint-Pierre et Miquelon.‘ [The big trade and small fishing: Archeology of the 19th and 20th centuries at Anse à Bertrand, Saint-Pierre and Miquelon] Revue d'Archéologie contemporaine 1 (2021), pp. 59-80.

- Florence Levert, ‚Au bonheur de l’ethnographe, à Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon.‘ [To the happiness of the ethnographer, in Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon.] Ethnologie francaise 37, 2 (2006), pp. 495-496.

- Nicolas Landry, ‘Étude du risque dans la vie maritime autour de Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon 1817–1948.’ [Study of risk in maritime life around Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon 1817–1948.] Newfoundland and Labrador studies 34, 2 (2019), pp. 231-270.

- Ronald Rompkey,. Terre-Neuve : Anthologie des voyageurs français, 1814-1914 [Newfoundland: Anthology of French travelers 1814-1914]. (Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2018).