The Nordic Countries and Humanitarianism

How the development of overseas aid led to the Nordic countries perceiving themselves as humanitarian “great powers”

Summary: Humanitarianism has been a defining feature of Nordic international engagement since the beginning of the 20th century. Its evolution from individual initiatives to a state-led, institutionalised, and globally recognised tradition reflects both continuity and strategic adaptation. After the end of the Cold War, Nordic humanitarianism adjusted to new geopolitical conditions, while ‘humanitarian interventions’ in places like Somalia and Kosovo challenged traditional Nordic principles of peace and neutrality. Nordic humanitarianism in the 21st century is confronted with challenges such as protracted conflicts, politicisation of aid and increasingly extreme weather events. The Nordic countries continue to uphold their reputation as humanitarian leaders, both through national policies and civil society organisations although not without critique.

Unlike cultures that prioritise self-promotion and grandiosity, Nordic societies tend to emphasise a low-key, results-oriented approach. Internationally, they are recognised as humble and efficient team players who contribute constructively to politically viable solutions. However, there is one striking exception: humanitarianism. In this field, the Nordics do not merely participate in collective efforts in a pragmatic small state manner – they assert a leadership role and even describe themselves as “great powers”. What underpins this self-image?

Humanitarianism and the Nordic self-perception as a ‘humanitarian great power’

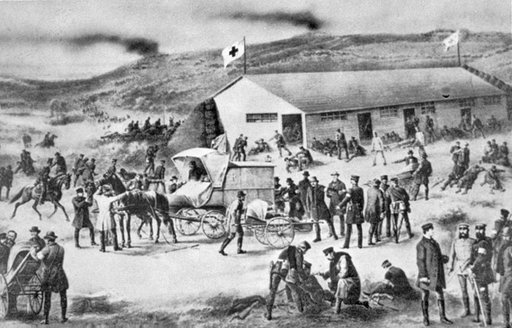

There is no universally accepted definition of humanitarianism, but as my colleagues and I concluded in our book on humanitarianism, voluntary emergency aid lies at its core (Götz, Brewis, and Werther 2020). Broader interpretations may also encompass government action, development assistance, and human rights advocacy. State involvement includes multilateral initiatives, contributions to UN missions and ‘humanitarian interventions’ that use military force to protect vulnerable populations. Armed conflict is regulated by international humanitarian law, which is in turn rooted in the Geneva Conventions that were adopted in 1864 in connection with the establishment of the International Committee of the Red Cross. In the Nordic countries, governments are seen as constituting the centre of the national humanitarian system, coordinating and collaborating with a cluster of voluntary organisations and corporatist bodies that specialize in the field. This contrasts with other Western countries, where humanitarian efforts are more independently driven by civil society.

The Nordic self-perception as a ‘humanitarian great power’ illustrates the significant role that governments play in shaping and directing Nordic humanitarianism. Denmark was one of the twelve signatories of the 1864 Geneva Convention, and Sweden and Norway ratified it in the same year. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, these countries increasingly acquired a profile of constructive engagement for international conflict settlement.

The evolution of Nordic humanitarianism in the early 20th century

Pivotal figures in shaping the Nordic countries’ reputation as key humanitarian proponents were the Swedish missionary Alma Johansson (1881–1974), the Swedish nurse Elsa Brändström (1888–1948) and the Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen (1861–1930). During the First World War, Johansson witnessed the mass deportations and massacres of Armenians. She played a crucial role in documenting the Ottoman genocide on the Armenians as well as in fostering Nordic fundraising and relief efforts for survivors. Similarly, Brändström’s relief work on behalf of the Swedish Red Cross for prisoners of war held in Siberian camps was followed by a publication that helped fund further humanitarian work. As an explorer, Nansen was already a celebrity before his high profile in Soviet famine relief and refugee work in the 1920s. He became the League of Nations’ first High Commissioner for Refugees and developed the so-called Nansen Passport, which provided stateless refugees – especially displaced Russians after the 1917 revolution – with legal identity and travel rights. Not only Nansen, who was significantly backed by the Norwegian government and awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922, but also figures like Johansson and Brändström became symbols of national pride in their home countries and had a major share in establishing an internationally acknowledged tradition of Nordic humanitarianism.

At the same time, institutional developments, such as the evolution of the Red Cross as a strong popular movement in the Nordic countries or the major role of Nordic branches in the transnational Save the Children network, laid the foundation for Nordic humanitarian identities. Sweden, Norway, and Denmark took active roles in the League of Nations’ humanitarian work, and their Red Cross societies and labour movements expanded their activities to assist refugees and displaced populations in Europe.

The effects of the Second World War on Nordic humanitarianism

The Second World War marked a further step in the development of Nordic humanitarianism. Neutral Sweden became a key hub for aid efforts, providing refuge to those fleeing war and Nazi persecution, including Finnish children and thousands of Jews from Denmark and Norway. The diplomat Raoul Wallenberg saved large numbers of Jews in Budapest by distributing protective passports, while Folke Bernadotte of the Swedish Red Cross orchestrated the renowned ‘White Buses’ operation, rescuing concentration camp prisoners in the final weeks of the war. In German-occupied Denmark and Norway, underground resistance networks engaged in humanitarian activities ranging from smuggling refugees to providing medical care.

After the Second World War, the establishment of the United Nations provided a new arena for engagement, with Nordic diplomats playing leading roles in shaping humanitarian frameworks. Sweden, Denmark, and Norway were among the six countries providing medical support to UN forces during the Korean War. Later the Nordic countries, including Finland, emerged as some of the most prominent contributors to UN peacekeeping missions. From the mid-1960s, the Nordic countries were also strong proponents of international development assistance. Sweden, Norway, and Denmark became the most generous donors of official development assistance, consistently surpassing the UN target of 0.7 per cent of GDP for development aid (Ekengren and Götz, 2013).

State-driven Nordic humanitarianism in the post-war era

In the post-war decades, Nordic humanitarianism became increasingly state-driven. Building on earlier civil society networks, governments institutionalised their commitment to foreign aid by establishing development agencies such as SIDA (Sweden, 1965) and NORAD (Norway, 1968). While voluntary humanitarian organisations remained significant, they increasingly operated within state-sponsored frameworks, receiving funding and mandates from national governments.

A notable exception to state dominance in the Nordic humanitarian sector was the Biafran War (1967-1970), when church aid organisations and the Red Cross played a pivotal advocacy role alongside the mass media. Their lobbying efforts pushed Nordic governments toward a more pro-Biafran stance than diplomatic caution toward a secessionist regime would have ordinarily suggested (Götz and Marklund, 2024). Despite Biafra’s defeat, the crisis became a watershed moment for modern humanitarian advocacy and fundraising in the Nordic region and across the Global North. It marked a breakthrough of human rights frameworks in humanitarian discourse. In the Nordic countries, the Biafran War led to comprehensive cooperation between national church aid organisations, who established the collaborative platform NordChurchAid with a secretariat in Copenhagen. The conflict also reinforced a humanitarian approach rooted in neutrality and solidarity, and it consolidated the comprehensive civil society cooperation and public–private partnership that mirrored the corporatist structures of the welfare state (Marklund, 2016).

Challenges to Nordic principles of peace and neutrality since the end of the Cold War

With the end of the Cold War, Nordic humanitarianism adapted to new geopolitical conditions. The wars in the Balkans in the 1990s saw significant Nordic engagement, including peacekeeping missions, humanitarian aid, and diplomatic mediation efforts. At the same time, ‘humanitarian interventions’ in places like Somalia and Kosovo challenged traditional Nordic principles of peace and neutrality, as military force became increasingly integrated into humanitarian efforts.

In the twenty-first century, Nordic humanitarianism is confronted with new and evolving challenges. Protracted conflicts, rising migration pressures, and the increasing globalisation and politicisation of aid have complicated the traditional Nordic approach. Additionally, climate change and the growing number of extreme weather events have made environmental crises a central humanitarian concern, with Nordic countries taking a leading role in linking humanitarian aid with climate adaptation efforts.

Facing such challenges, the Nordic countries continue to uphold their reputation as humanitarian leaders through national policies and civil society organisations alike. However, the self-proclaimed status of ‘humanitarian great powers’, as some Nordic politicians have described their countries, is not without critique. Some argue that Nordic humanitarianism primarily is a tool for national identity-building and soft power projection, rather than an expression of altruism. Others point to contradictions, such as restrictive asylum policies that seem at odds with professed humanitarian values. Meanwhile, populist political movements call for radical cuts in aid budgets and the dismantling of the close public–private partnerships that underpin the Nordic humanitarian sector.

Nonetheless, humanitarianism remains a defining feature of Nordic international engagement. Its evolution from individual initiatives in the nineteenth and early twentieth century to become a state-led, institutionalised, and globally recognised tradition reflects both continuity and strategic adaptation. However, although the legacy of Nordic humanitarianism is firmly established, its future path in a rapidly changing global landscape is difficult to predict.

Historical reputation can inform political decisions in the present.

This article was published in response to readers' interest in the Nordics role in humanitarian aid.

Further reading:

Ann-Marie Ekengren and Norbert Götz, ‘The One Per Cent Country: Sweden's Internalisation of the Aid Norm’, in Saints and Sinners: Official Development Aid and its Dynamics in a Historical and Comparative Perspective, ed. Thorsten Borring Olesen, Helge Ø. Pharo, and Kristian Paaskesen (Oslo: Akademika, 2013), 21–49.

Carl Marklund, Neutrality and Solidarity in Nordic Humanitarian Action (London: Overseas Development Institute, 2016).

Norbert Götz, Georgina Brewis, and Steffen Werther, Humanitarianism in the Modern World: The Moral Economy of Famine Relief (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Norbert Götz and Carl Marklund, eds., Biafra and the Nordic Media: Witness Seminar with Uno Grönkvist, Lasse Jensen, Pierre Mens, and Pekka Peltola (Huddinge: Södertörn University, 2024).