The Nordic Countries at the Start of the Cold War

Divergent experiences during the Second World War set the stage for the Nordic countries’ different approaches to Marshall Plan aid and NATO.

Summary: Each of the five Nordic states experienced the Second World War very differently, and this had a large impact on their future development. Iceland, Norway and Denmark opted for further cooperation within NATO, and Sweden and Finland opted for neutrality. In all five cases, it was their experiences during the Second World war and the different geopolitical positions of each country that determined the choices they made during the Cold War.

The Nordic countries after the Second World War

The Second World War completely changed the picture of security policy in Europe. The Nordic countries came out of the war having had very different experiences, and relating to the rest of the world in very different ways. They emerged into a geopolitical picture that had completely changed. Germany was beaten and split into two. The Soviet Union and the United States were the world's most powerful military and economic powers, but now on each its own side in the dispute over ideology and security policy that we know as the Cold War.

Iceland

Iceland became independent in 1918, but was in a personal union with Denmark and thus had Christian X as king. Located in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, the country immediately acquired strategic importance with the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. Iceland had been declared neutral, but otherwise had no military with which to assert its neutrality. While Germany quickly gained the upper hand militarily on the European continent during 1940-41, Britain aspired to dominate the oceans with its Royal Navy. However, British domination of the seas was not a given as Germany also had a powerful navy, not least with its much-feared submarines. Britain occupied Iceland in May 1940 without any shot being fired, but the Icelandic government protested against the violation of its neutrality.

In July 1941, by agreement with Great Britain, the United States took over the occupation of Iceland without consulting the Icelandic government. The United States then built up the Keflavík base on the western side of the island. Iceland declared itself a republic in 1944, severing the last ties to Denmark and Danish royal power. Iceland joined the United Nations in 1946 and joined NATO in 1949, still without having a military. The country, however, was protected by US forces, who only left the island in 2006. The more than 60 years of American presence continued to be contentious in Icelandic domestic politics throughout the Cold War.

Norway

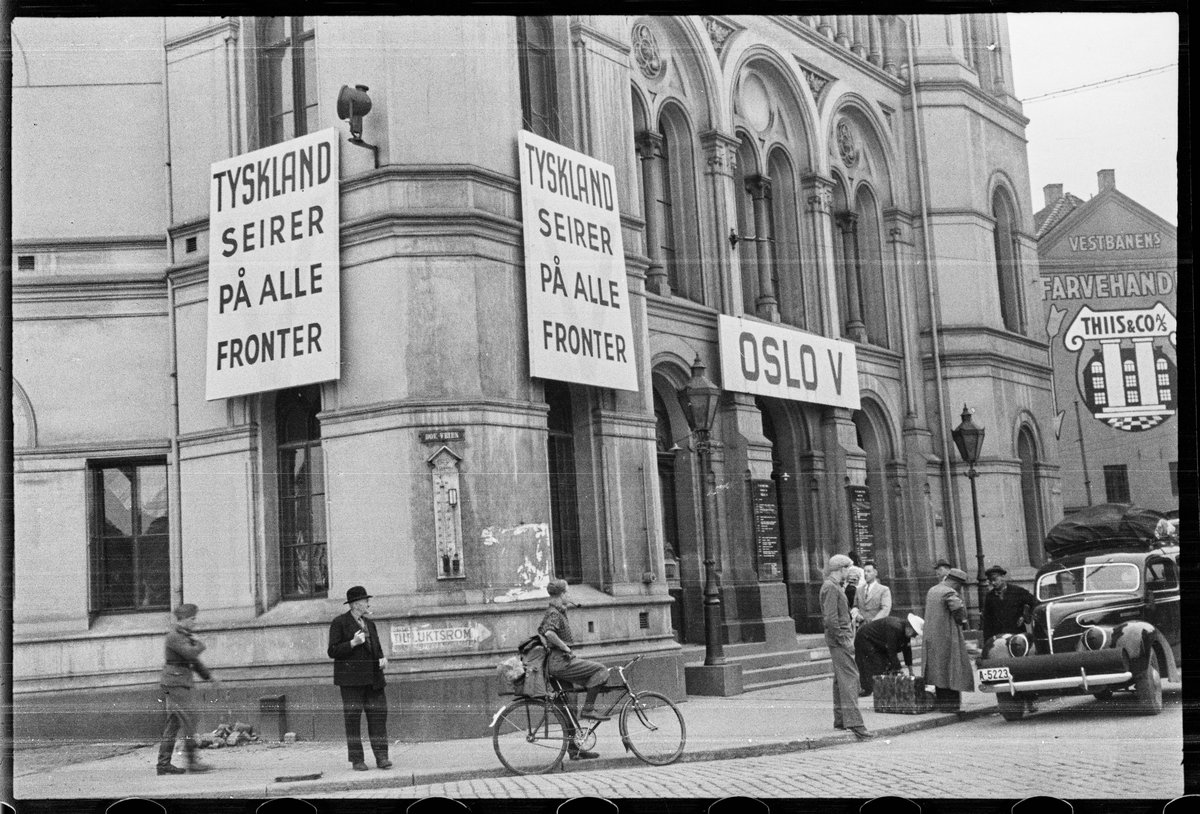

When Norway was occupied by Germany on 9th April 1940, Oslo was immediately lost to the German forces, at the same time as a Norwegian Nazi government seized power in the capital and took control over the entire country. The legally elected government, the royal family and the armed forces withdrew north while military combat against the invading forces continued until it was decided to give up the fight in June 1940. The government and the king then fled to London where a government-in-exile was established. After that, there was no significant military activity in southern Norway, which was occupied by Germany. A Norwegian resistance movement also emerged, but it never acquired the same military strength as the Danish. Northern Norway was also occupied by Germany, but throughout the war was frequently troubled by Soviet bombardment. The German troops in Norway surrendered without battle on 8th May 1945. After this, the government-in-exile from London returned to take over legitimate control of Norway, becoming a member of the United Nations in 1945.

Denmark

Denmark's fate during the Second World War was significantly different from Norway's. The country was invaded by Germany on 9th April 1940, but capitulated the same day, after which Germany became the occupying power in the country. The government and authorities then entered into ongoing negotiations with the occupying power in order to allow the occupation to proceed with the least inconvenience to the Danish population, while at the same time meeting Germany’s security requirements. While Denmark retained much of its domestic independence, it was in reality subject to Germany's military will. A resistance movement emerged in 1942, which grew larger towards the end of the war. This aggravated the conditions under occupation, especially from 29th August 1943 when the Danish government resigned, thus breaking off cooperation with the occupying power. Denmark was liberated by British troops on 5th May 1945. This happened without any fighting, except on Bornholm where the Soviet Union occupied the island after several major aerial bombardments. The Red Army left the island in April 1946. Denmark became a member of the UN in 1945.

Sweden

Sweden remained neutral throughout the Second World War. Despite a very strong military, the country was under considerable pressure to cooperate economically with Germany, and it also had to make military concessions in the form of transporting German troops on the Swedish railway. This seriously tarnished the country's alleged neutrality and its international reputation. In the final years of the war, Sweden pursued a less accommodating policy towards Germany, while relations with Britain and the United States were strengthened. Sweden became a member of the United Nations in 1946. This was a year after Norway and Denmark, and must be attributed to the Swedish government's concessions to Germany and Sweden's generally weakened international reputation.

Finland

Finland's position in the Cold War was also clearly determined by its experiences of the Second World War and geopolitics. Finland had been at war with the Soviet Union from 1939 to 1940 and again from 1941 to 1944. The first period had been because the Soviet Union attacked, as a result of which Finland had to cede territory despite an heroic struggle. The second period of hostilities was triggered by a Finnish initiative and this led to Finland fighting side by side with Nazi Germany to regain the lost territory. However, the Soviet Union fought back, and peace was laid out in the Soviet Union's terms with land cessions and demands for Finnish neutrality. Finland was effectively treated as a defeated country by the Soviet Union. Throughout the Cold War, the Soviet Union's shadow weighed on Finland, which, despite its status as a Western democracy, was forced into alignment and cooperation with the Soviet Union. It was a symptom of all this that Finland was the only Nordic country not to receive aid under the Marshall Plan; the Soviet Union simply would not accept it.

Co-existence of Nordic and national identity

From the mid-19th century until today, the Nordic countries have been characterised by a significant cultural and popular community, which has often taken on the character of an integrated part of the nationalism of the five nation states. Nordic identity has been able to exist without being in opposition to each country’s national identity, as opposed to the understanding one had of the relationship with Europe, which was typically perceived as something fundamentally different from nationality. Nordic citizens who perceived themselves as Europeans – and who existed predominantly among the cultural elites – were typically considered to be less national. If you were a declared ‘Nordist’, you were usually perceived as at least as national as other patriots. Nordism was an extension of the national, almost a strengthening of the national.

A Scandinavian attempt to join forces

In light of the considerable security tensions that arose in 1946 and 1947 between the Soviet Union on the one hand and the Western allies USA, Great Britain and France on the other, Norway, Denmark and Sweden began discussions in 1948 about the formation of a Scandinavian defence alliance. The threat these countries wanted to protect themselves from was first and foremost the communist Soviet Union, but there was also a concern that Germany’s military strength would be restored (which never transpired). Denmark and Norway had traumatic experiences from being under occupation, and only very weak military forces, while Sweden’s military was very strong and it was also a producer of weapons. However, negotiations failed in February 1949 when the parties were unable to agree. Norway looked to the United States and Great Britain for support, including weapons and guaranteeing its protection. Sweden wanted a detached alliance that saw itself as a neutral bloc positioning itself between the great powers. Denmark’s was set on the defence league taking shape and it was therefore amenable to both the Norwegian and Swedish vision. Eventually, Norway withdrew from the negotiations and joined the newly founded Atlantic Alliance (later NATO) in February 1949. After short - but from the Danish side desperate - negotiations about a two-sided alliance in which Sweden was not really interested, Denmark followed the same path as Norway a few weeks later. Sweden then maintained its neutral status until it applied for admission to NATO in 2023.

Different positions influenced the Nordic countries' actions

The negotiations for a potential Scandinavian defence alliance were characterised by the different preferences of each country, which stemmed from both their experiences during the Second World War and their disparate geopolitical positions at the time. Norway had established good relations with both Britain and the United States through its government-in-exile in London. With its location on the Atlantic coast and its large merchant fleet, Norway was generally more orientated westward. However, the need for military protection against the Soviet Union could not be ignored, especially on the northern flank where Norway shared a border with it, which it had felt only too much during the war. Denmark was heavily influenced by the trauma it had experienced during German occupation, where the country's vulnerable geography without natural defences had been made so abundantly clear; it had given Denmark an almost fatalistic approach, namely, that nothing could be done against an attack from a greater power apart from forming an alliance. However, the country's exposed position at the mouth of the Baltic Sea – the Soviet Union's western route to the oceans of the world – meant that Denmark’s inclination for a confrontation with its large neighbour to the east was not after all so great. This echoed the vulnerability it had felt towards Germany since at least 1871, leading to the particular prudence it had showed its neighbour to the south. Denmark’s inclination was in the 1940s like before: necessary adaptation to the nearest great power. Therefore, the Swedish vision of a free-standing alliance – i.e. a kind of neutral alliance – had a certain value during the negotiations, but when Norway became a member of the Atlantic Alliance and Sweden was uninterested in a two-sided federation, Denmark decided to also go down the Atlantic Alliance route. Sweden, on the other hand, continued to choose neutrality, opting for a tradition that had existed since the beginning of the 1800s. However, it emerged after the end of the Cold War that Sweden was not quite as neutral as it had wished it to appear. Secret agreements had been concluded with the United States and NATO for support in the event of an open dispute with the countries of the Warsaw Pact.

Three Nordic countries – Iceland, Norway and Denmark – opted for further cooperation within NATO, while two countries – Sweden and Finland – opted for neutrality. As we have shown here, in all five cases it was the countries' positions and experiences during World War II and geopolitical conditions that determined the choices made in relation to alliance relations and position in the Cold War.

Putting a spotlight on previous conflicts helps to illuminate today's security situation.

This article is published in response to readers' interest in historic wars in Europe, particularly since the invasion of Ukraine.

Further reading:

- Niels Wium Olesen, Claus Bundgård Christensen, Joachim Lund, and Jakob Sørensen, Danmark besat: krig og hverdag 1940-1945 (København: Informations Forlag, 2020).

-

Marie Cronqvist, Rosanna Farbøl, and Casper Sylvest, Cold War Civil Defence in Western Europe: Sociotechnical imaginaries of preparedness and survival (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022).

-

Henrik Lundtofte, Mona Jensen, and Flemming Just, War and Society in Scandinavia 1914-1950 (Odense: Syddansk Universitetsforlag, 2009)

Continue reading about the Cold War with our other article: the Nordic Countries during the Cold War.