Children’s Broadcasting in the Nordic Region, 1960-1990

A comparison between the Nordic countries’ and the USA’s approach to the TV programme Sesame Street from 1960-1990.

Summary: The US show Sesame Street, which started in 1969, was seen as groundbreaking and each of the Nordic Broadcasting Corporations considered whether to buy the format or not. Their discussions, both internally and with the team behind Sesame Street, reflect the different views of childhood between the US and the Nordic countries. These views arguably still inform both children’s television and the countries’ different approaches to childhood today. Note: In this article, Scandinavia refers to Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden.

Why is children’s media consumption seen as so important?

Society generally is very invested in how children spend their time, probably because today’s children will be responsible for forming how the world looks tomorrow. Children’s media consumption is therefore often the focus of heated debate with strong opinions being voiced. For example, ’media-panic’ about the quantity of media consumption, concerns about violent or extreme content, and streaming, where the child is more likely to choose what they watch rather than an adult being a gate-keeper.

Adults – be it parents or producers of media – often have a particular image of what type of adults children should become and, in this way, they can try to transfer their values or past values on to future society (this can be called “enculturation”). This can be seen in media production and in public debate. It can also be seen in the way parents or guardians act as intermediaries or as co-consumers of media aimed at children. These ideals can seep into media aimed at children and influence production and programming.

On top of that, people often have a romanticised view of childhood as innocent and something which should be protected. Views of childhood are, however, different from country to country, region to region, and are influenced by things like class. Middle class values often dominate children’s media, also in Scandinavia. These sorts of issues have led some scholars to see childhood not as a biological life stage, but the outcome of historical, social and cultural ideas at a given time and place.

The child as a competent citizen

The late 1960s and early 1970s saw a change in the way children were perceived in the Nordic countries. Although approaches and policies differed across each country throughout this time period, it is possible to say that children came to be seen more as competent citizens in their own right.

This sea change came about for various reasons, but the cultural revolution of 1968 was definitely decisive. In response to this – and to Gunilla Ambjörnsson’s book Skräpkultur åt barnen (Trash Culture for Children, 1968) – debate about children’s culture took place across Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Some believed that equality and welfare for all, the classic focus of the 1968 movement, also extended to children. In her book, Ambjörnsson criticised virtually all the products available to Swedish children, arguing that historical and contemporary plays, literature, TV programmes and film all failed to give them a handle on reality and thus did not take them seriously as individuals. This all led to the Nordic Council of Ministers organising in 1969 a symposium entitled ‘Children and Culture’, which took place in Sweden, where 10 principles were formulated. They stressed above all children’s equal worth as human beings and their right to be treated as such in all aspects of life. Children’s interests should be taken seriously, value should be placed on children’s culture (their way of living), and they should participate in making decisions over their own lives.

The people who worked in children’s television at the national broadcasting corporations (SR in Sweden, NRK in Norway, YLE in Finland, RÚV in Iceland, and DR in Denmark) were also influenced by the idea of the child as a competent citizen and many attended this conference, or were part of the Working Group for Children and Young People in the Nordic Broadcasting Union (Nordvision, which was founded in 1959). Public service broadcasting aimed to inform, educate, and entertain its viewers. The broadcasting institutions were independent institutions funded by license fees and there was only limited oversight by boards of governors. This financial model gave the broadcasting institutions freedom to develop independently as they did not have to act on behalf of political institutions or sell commercials to finance their content.

The vision established at the 1969 conference was carried over to the 1970s (and arguably later on), and the Nordic broadcasting corporations sought to emphasise children’s culture as something different from adults’ culture. Children should not be addressed as subjects of their family or the educational system, but should be empowered and emancipated.

The wish to use television in a positive, structured manner to support a variety of goals, including greater equality, a better-educated workforce and ultimately higher living standards was not that different from the rest of Europe – and to a certain extent those behind Sesame Street. For example, there were also child-centred trends in the UK and West Germany at the time. But comparative studies strongly suggest that the Scandinavian ideas were somewhat more radical in the inclusion of children’s voices, promoting a utopian form of progressivism where children were treated as equal to adults. These factors contributed to broadcasters in the Nordic countries approaching children’s TV programming rather differently than the producers of Sesame Street.

The story of Nordic Sesame Street

Through reviewing much of the relevant meeting notes from the time, I found out that the idea of some sort of Nordic Sesame Street started in 1970. Sesame Street was a very popular and well-regarded show in the US, and the UK and West Germany regional stations began to air some parts of the show and its format in 1971 and 1973 respectively. The Nordic broadcasting corporations were all contacted by the Workshop, the team behind Sesame Street, with a view to buying the format for their state channels or to create a collective programme, and they were impressed and interested to find out more. Full co-production between the Workshop and other channels was the biggest money-spinner for the Americans because, if they wanted to stay commercial-free in the US where this was the usual funding model, they had to make money elsewhere. The idea of a “Nordic Sesame Street” specifically arose after a representative from the Workshop had visited DR and SVT in late 1970. Though somewhat concerned with the show’s educational approach, the Nordic broadcasters wanted to try out the aesthetic format because children found it very attractive. A pilot was produced in Swedish and Danish in 1972, and a Norwegian one was planned too, but in the end the Sesame Street team’s approach to education and the child-adult relationship was deemed just too different to be adaptable to a Nordic context.

Over the decades from the late 1960s, co-productions of Sesame Street were carried out in French, Spanish, West German, Flemish, Latin American and pan-Arabic versions.

Ultimately, however, only the national broadcaster in Sweden actually aired a generic variation of the original Sesame Street (which was called Open Sesame) during 1976 and later, in 1980 and 1981, ran a version where a third of the content was produced in Stockholm. It was not until 1991 that Norway began airing a co-production, Sesam Station which ran for eight years (198 episodes). In Denmark, a spin-off, Elmo’s Corner (Sesamgade), ran for three seasons from 2009 to 2013, but it was not a big success. In Finland, YLE showed a program called Sesamtie from 1997–2000. Only Iceland has not made its own version of the program.

The lack of success – and the fact that Nordic Sesame Street never happened – highlights two important points:

- From an early stage, Nordic broadcasting corporations worked together and exchanged ideas through formal and informal ways. They had, and still have, a united tradition of child-centered broadcasting.

- The different approaches of the Nordic broadcasters on the one hand, and Sesame Street’s American producers on the other, provide a useful case study in cultural differences to television and childhood at the time, some of which arguably filters down to today.

There were of course differences across the Nordic countries, but several reasons why Nordic Sesame Street did not come to be a reality were similar, and these included:

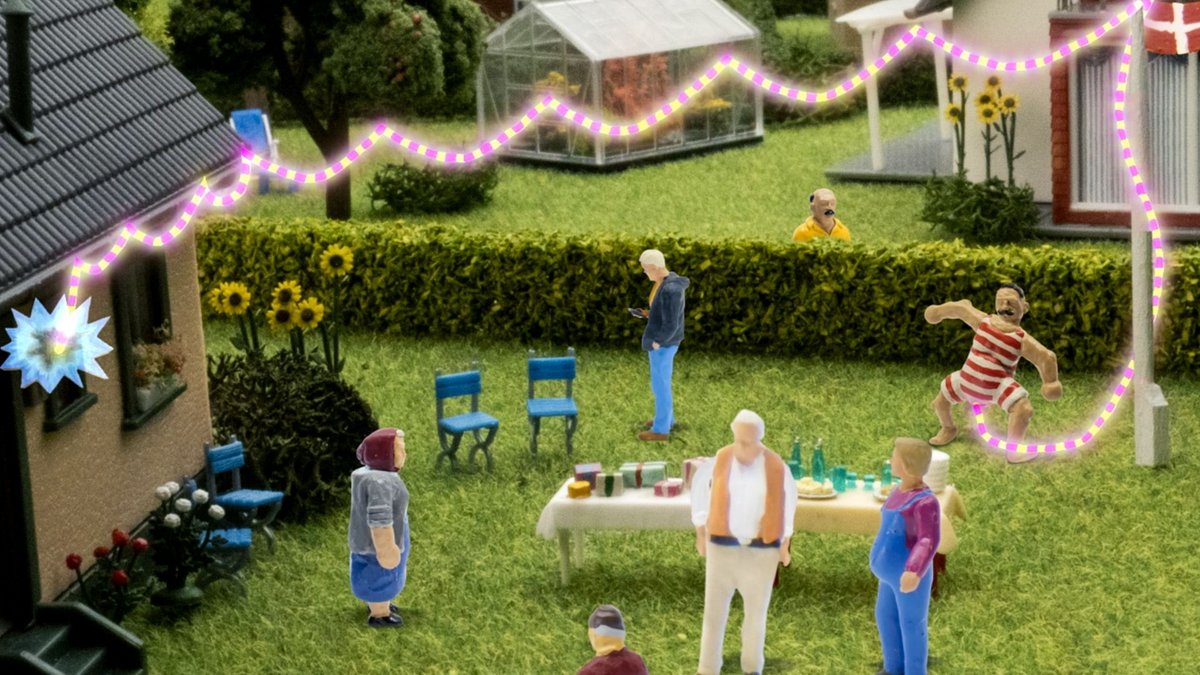

The purpose of pre-school TV was interpreted differently: Sesame Street first aired in the United States in 1969. The company that produced Sesame Street wanted the show to be for school-like, educational purposes, whereas the Nordic TV producers wanted to distance their programmes from the educational system, and be more anti-authoritarian, encouraging children to take control of their own lives. For example, one of the primary aims of Play Room (Legestue) on DR at the time was to inspire children to do a range of activities away from the screen, particularly arts and crafts and outdoor games, giving them a sense of themselves and their surroundings that would enable them to explore the world on their own. Exploring hobbies (animals, games), daily life (meals, routines), emotions (sibling rivalry, friendships), and society at large (life in other countries, pollution, energy, food production), it was a much slower-paced program, made on a shoestring budget.

Commerciality and how it was addressed: The Workshop were actually well-known for their stance against the commercial system in the US. They also had a particular aim to target underprivileged children in urban areas and they wanted to help preschoolers who were not exposed to education through their family or social circumstances. Yet, their modes of working still appeared to be more commercial than their Nordic colleagues. The Nordic broadcasters thought Sesame Street was considered to be too long and fast-paced – it was too pacifying. The Workshop was also unavoidably a commercial entity, needing to make money, which also put off the Scandinavians, including their reliance on merchandise and international sales – exemplified by the effort they put in to trying to sell the format to the Nordic countries.

The experimental approach: Sesame Street had a strong focus on the universal need for television to teach a specific set of skills and this contrasted sharply with the Scandinavian approach, which was much more experimental. In Scandinavia, education was seen as a political thing, and orthodox views and research – including that carried out by the well-paid researchers at the Workshop – about children and education were questioned. National broadcasters in the Nordic countries experimented with ways in which their programs could empower children by supporting their sense of self, their understanding of the world around them, and their confidence to challenge adult authority. This even meant that older children were invited to write and produce films and policies explicitly conceptualised as television children's spokepersons. The more structured and regimented production modes in the Workshop did not fit this experimental model well, where learning was not guaranteed, but encouraged through play.

Practical considerations: Over and above the ideological differences between the US and broadly Nordic approach, there were fundamental practical issues that played a part in the decision not to make a Nordic Sesame Street. There were not many channels back then (and in some cases only one), and each of the Nordic countries had already developed their own pre-school programmes, and in some cases (such as DR) large children’s departments. SVT1 had Look, Play, Learn (started in 1965), DR’s Playroom (Legestue, started in 1969), and NRK’s Lekestue (an adaptation of the BBC’s Play Room). The Nordic television producers did not want these initiatives to be overshadowed by Sesame Street or resources diverted away from their own programmes.

The Nordic broadcasters strongly admired the Workshop’s budget, the size of its research team, the agreement to a fixed set of production rules, Sesame Street’s high aesthetic value and the Muppets' popularity amongst children. Their staff generally agreed that the quality was very high, and the use of music was impressive. Most believed the show’s success was due to teamwork: Everyone at the Workshop seemed to have a designated role matching a specific part of the show. The show’s popularity was put down to its decoration and the fixed set of humans and Muppets, which children would recognise and become attached to. But ultimately, Sesame Street did not seem right for the Nordic broadcasting corporations.

Are some of these differences still alive today?

Today’s complex broadcasting and media landscape would be almost unrecognisable to the TV production teams of the 1970s. However, some of today’s principles can be to a greater or lesser extent traced back to that time. In the last decade, there has been international commentary on, for example, the dissection of a baby giraffe in front of children at Copenhagen Zoo, the DR programmes ‘Ultra [the children’s channel] Throws Off Their Clothes’ (Ultra smider tøjet), and ‘John Willyman’ (John Dillermand).

Popular and academic literature try to place what is specifically ‘Nordic’ about childhood and growing up and, despite globalisation, there are some characteristics that are more similar across the Nordic countries than elsewhere. There is arguably still an intention to stimulate children’s sense of themselves, their everyday lives, and society as a whole, helping them to see and challenge social power structures – including the assumption that adults have a natural authority. With some important exceptions, most of Nordic children’s television remains less obviously didactical than the US.

This article is based on a chapter of the author’s book, Sesame Street: A Transnational History published by Oxford University Press in 2023.

History can shed light on practices to do with Nordic childhood

This article is published in response to readers' interest in both Nordic childhoods and public service broadcasting.

Further reading:

- Helle Strandgaard Jensen, 'La télévision scandinave pour enfants dans les années 1970 : une institutionnalisation du « 68 scandinave » ?', [Scandinavian children's television in the 1970s: an institutionalization of the "Scandinavian 68”] (2018) Strenæ, 13.