Cross-country Skiing and Nordic Identity before the Second World War

Representations of cross-country skiing since the 1800s reveal that the sport has been an important cultural marker for Nordicness.

Summary: Since the mid-19th century, cross-country skiing has been perceived as a cultural marker for Nordicness. The Nordic Games launched in 1890 prominently featured skiing competitions, and skiers from Norway, Sweden and Finland dominated the early Olympics, often in fierce competition with each other. Nordic audiences eagerly consumed skiing competitions, first through attending live events, and later through print and radio. Media coverage reinforced assumptions that cross-country skiing somehow constituted the epitome of being Nordic and laid the foundations for skiing's role in Nordic identity today.

19th century romantics and skiing as a cultural practice

As a means of transportation, skiing has a history in Norden that reaches beyond written record, and the first archaeological evidence of skiing in the region is more than 5000 years old. Then, during the 19th century, as modern nationalism and romanticism grew, so too did the notion that skiing was not only practical, but also a cultural marker setting Nordic people aside from others. This idea gained traction and turned skiing through Nordic nature into an integral part of many nationalist expressions. In Sweden, the legend of how the 16th century outlaw king Gustav Vasa eluded Danish oppressors by skiing formed an integral part of the national history, while Finnish ethnologist Elias Lönnrot made stories of ancient heroes on skis pursuing monsters publicly available as symbols of Finnishness through the Kalevala epic. However, it was above all else in Norway that skiing would become an inescapable part of national identity, as legends of skiers of the past, such as the Birkebeiner (see picture above), were used to historically underpin skiing’s role as the go-to activity of choice for all Norwegians as a pasttime.

The turn of the century: elite skiing competitions are born

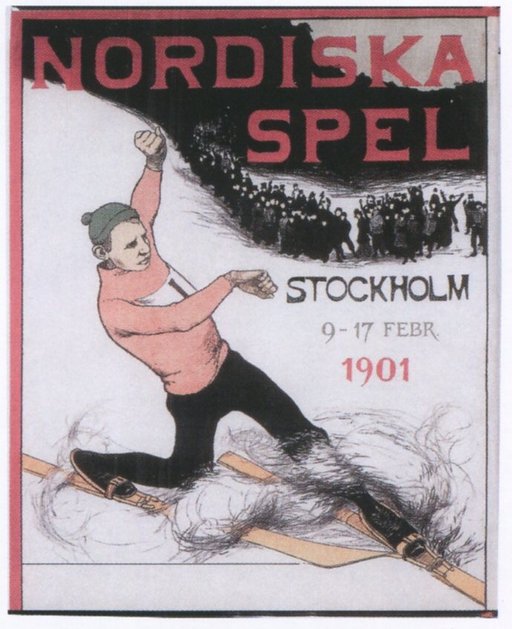

Skiing then turned from a cultural expression into a way of competing as traditional Nordic skiing mingled with the development of the modern sports infrastructure emerging from Victorian Britain and elsewhere. Sámi ski culture would, not least, play a crucial part in the creation of skiing as a modern sporting and spectator event: When revealed to representatives from Nordic national skiing centres, the speed of Sámi skiers inspired the launch of races at the national level. Because of the climate and landscape, however, cross-country skiing in Norden has remained largely limited to Sweden, Finland and Norway, so when things are talked about as “Nordic” in skiing, they are in reality really only talking about something that is relevant to particular parts of the region. Nonetheless, when the “Nordic games” were launched in Stockholm in 1901, their focus lay wholly on winter sports, simply because the organisers considered sporting on snow and ice as the most apt way to display Nordicness.

The interwar era: the birth of the modern media spectacle

The Olympics started in 1896, but winter sports featured only on a limited scale prior to the First World War through ice sports such as figure skating and ice hockey. Skiing was wholly absent. This all changed during the 20s and 30s as the emergence of major international ski competitions coincided with the advent of new media systems, leading to lasting changes in the relationship between Nordic identity and representations of skiing in the media.

The Nordic countries originally opposed the introduction of the Olympic Winter Games in 1924, partly due to an urge to keep Nordic skiing disciplines exclusively Nordic. This resistance, however, was soon overcome, and Sweden, Norway and Finland were to send athletes to compete at the games from its inaugration and onwards. Nordic skiers went on to completely dominate the Olympic cross-country skiing events, and were often in fierce competition with each other for the top spots. And while the interwar games took place far from Norden, in either the Alps or North America, Nordic audiences still eagerly consumed news about the games through newspapers and, from the 1930s and onwards, through the emerging medium of radio. The radio could portray and frame emotions in a different way to the written word, and broadcasts of elite cross-country skiing competitions became eligible for mass consumption, turning the Winter Games into major media events in particularly Sweden, Norway and Finland.

In 1925, the Winter Olympics were joined in the sporting calendar by the International Ski and Snowboard Federation (FIS) world ski championships, and broadcasts of the event (mostly known in Norden simply as the biannual “world ski championships”) have garnered large media interest ever since. However, these games only included cross-country skiing and ski jumping, and could thus not match the Olympic games’ ability to invite audiences to compare and contrast Nordic ski cultures to other imagined geographies. The Olympic smorgasbord of various winter sports was also ratcheted up a notch in 1936 when the programme included alpine skiing for the first time. In Norden, the media portrayed the alpine events as simply a fun pastime, and one not even remotely able to test the true qualities of manly endurance and perseverance in the ways that cross-country skiing could. Indeed, newspapers saw the successes of Nordic men in cross-country skiing as a sign that they possessed stamina and persistence - a specific kind of masculinity that other men did not possess. Cross-country skiing thus became a symbol of Nordic masculinity, and it is perhaps telling, then, that, while women featured in alpine Olympic events already from 1936, cross-country skiing remained an all-male event until 1952.

Interwar media narratives not only highlighted the discrepancy in results between Norden and other places, but also contrasted the wide public interest cross-country skiing enjoyed in Norden compared to the rest of the world. For instance, Nordic newspapers in 1936 contrasted the few Germans that had turned up to watch the 50k cross-country ski race (despite many Germans participating) with the overall “Nordic” interest at home.

The media positioned desire for success in cross-country skiing as a typical Nordic trait, and this cemented not only differences between Norden and the rest of the world, but also perceptions of the relationship between Sweden, Norway and Finland:

- Firstly, stories of a pan-Nordic desire told national audiences what neighbouring countries wanted. This, paired with narratives of intra-Nordic sameness, would have inspired audiences to yearn even more for the same thing as their Nordic peers i.e. success in cross-country skiing.

- Secondly, these narratives undoubtedly led to the construction of rivalries between the three nations, because, even if Nordic successes could be lauded as signs of pan-Nordic competences, only one country at a time could win the sought-after gold medal; your own country’s success would therefore inevitably entail the defeat of your neighbour.

The post-war skiing landscape

The post-war skiing landscape was dramatically affected by the inclusion and successes of Soviet sportsmen and women which would alter, albeit not annihilate, notions of Nordic superiority. Media coverage of the Soviet winners – as well as those from other countries - both reinforced the narrative of ‘Northern’ hardiness, and at the same time undercut the perception that this sport should be solely a Nordic domain. Since 1990, like other sports, skiing – and its ‘pure’ natural image - has been challenged by commercialisation and doping scandals, but the narrative of Nordicness remains and the competition between Nordic neighbours spurs them on.

The pre- and interwar media history of cross-country skiing therefore reveals how representations of skiers configured Nordic imaginations of Norden’s place in the world, as well as the underpinnings and characteristics of the specific relationship that skiing enjoys with Nordic identity today.

Media history sheds light on comtemporary ideas.

This article is published as a response to readers' interest in Nordic identity and popular culture.

Further reading:

- Inga Löwdin, 'Tillbakablick på skidornas damlängdl ning som tävlingssport 1880–1965' [Looking back at women's cross-country skiing as a competitive sport 1880–1965], i Idrott, historia och samhälle, 1994, s. 41–59. (Stockholm: Svenska idrottshistoriska foreningen, 1981–, 1994).

- Jens Ljunggren, 'Tradition eller tävling? Nordiska spelen och kampen om vad idrott är' [Tradition or competition? The Nordic Games and the battle over what sport is], Historisk tidskrift (Stockholm) vol. 1997 (117), s. 351–374 (1997).

- Thor Gotaas, Norway: the craddle of skiing. Vol. 6. (Font Forlag AS, 2012).

- Vidar Martinell, Skidsportens historia: längd 1800-1949 [The history of skiing: from 1800-1949]. (Erlanders Graphic Systems, 1999).