The Baltic Sea Region and Ecocultural Identity

The Baltic Sea is on a faster trajectory of climate change than other sea areas. Already with the framework of the Helsinki Commission (HELCOM) in 1974, it was recognised that regional solutions were necessary to combat environmental degradation in the region. Additional threats are now posed due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Baltic Sea states (without Russia) still seek environmental progress for this complex ecosystem, arguably building on a legacy that stretches back to the 12th century. The concept of ecocultural identity combines ecology and culture, and recognises that sociocultural aspects of our identities are inseparable from ecological ones. Multi-level governance, cross-sectoral activities, and trans-boundary threats all testify to this interconnectedness.

Focus on the Baltic Sea Region

Focus on the Baltic Sea region is perhaps greater now than ever before in recent times. It is a region that is witness to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has pushed millions of Ukrainians to leave their worn-torn country and seek refuge elsewhere. The hybrid war poses numerous threats to the entire Baltic Sea Region, ranging from political destabilization and election meddling, through cyberattacks, to critical infrastructure sabotage, with one of the most notable examples of a hybrid threat being the Nord Stream pipeline explosions in 2022. Such incidents lead to the release of tons of natural gas into the atmosphere, which, in turn, increases the already high greenhouse gas emissions. Similar disasters may result in the resuspension of tons of heavy metal contaminants, which means that heavily contaminated sediment may be removed from the seabed as a result of an explosion, with disastrous consequences for fish and sea mammals, such as seals and harbor porpoises.

The picture is even more bleak when we remember that the Baltic Sea is already affected by pollution and climate change. Due to the proximity to chemical warfare agents dumped at sea at the end of World War II, even a small seafloor disturbance may release hazardous material into the water column. The protection of critical infrastructure in general, and pipelines in particular, is of primary importance, as Poland and other EU countries have decided to diversify their gas supplies through maritime and pipeline transportation of oil and gas.

There is also of course an increased risk of environmental harm arising from Russia’s war against Ukraine. With more than 250 rivers flowing into the Baltic Sea, not only from the territories of its coastal states but also Ukraine, the quality of the water flowing to the sea may be compromised, with air and water pollution spreading across state and administrative borders.

The Baltic Sea is in fact on a faster trajectory of climate change than other sea areas. It is an extremely complex marine space affected by local and global migration pressures due to military interventions, water conflicts, and the climate crisis, as well as by the reconfigured security environment, and by the particularly sensitive marine ecosystem.

What is 'ecocultural identity'?

Different scholars have defined ecocultural identity in different ways, but it can be described as a “more-than-human intersectionality” which leads “to shared questions, concerns, and actions regarding our collective course of living”*. It sheds light on:

who we are (human beings whose sociocultural identities are always ecological in nature); and, how who we are (how we think, relate to, and behave toward the more-than-human world) shapes our planet, in order to help us reimagine our identity (identities) and behaviors as inseparable from the biosphere.

(* With a nod to Nicholas Jackson in the Routledge Handbook of Ecocultural Identity and Tema Milstein.)

Regional cooperation: now and historically

The situation is further deteriorated by suspended regional cooperation between the Baltic Sea states and Russia. Even in the dark days of the Cold War the protection of the Baltic marine environment within the framework of the Helsinki Commission (HELCOM) was the key to the integration of the Baltic scientific community and keeping regional dialogue alive. That said, the Baltic Sea states (other than Russia) have shown a remarkable unity when faced with Russia’s military aggression toward Ukraine and its wide-ranging security impacts.

The Hanseatic League or Hanse occurred many centuries ago, but it still relevant to this day. With the city of Lübeck as its center, the Hanseatic League or Hanse was a medieval association of merchants from Northern Europe, a trade federation or a pre-modern league of cities, with its merchant fleet, administrative structures, and negotiating power – all coupled with its strong political and economic ambitions. Not only was it a network that shaped trade relations in northern Europe from the late 12th to the late 16th century, but it was also characterized by cultural exchange. Successful though the Hanseatic League was, it collapsed in the 16th century as a result of the growth of territorial states and changes occurring in the world economy. The Hanseatic past is still cherished by people in some of the cities in the Baltic Sea Region.

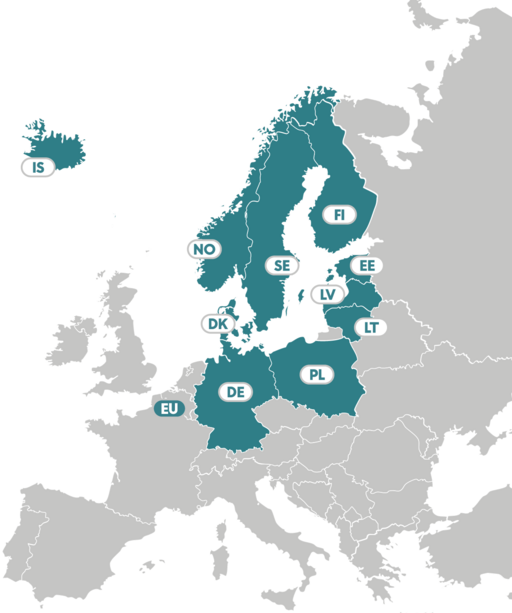

Hanse serves as a source of inspiration for contemporary political and economic structures of the BSR, e.g. the New Hanseatic League – a group of eight Northern European countries established to reform the Economic and Monetary Union of the EU, as well as to protect their interests. The countries include: Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, and Sweden. Historians as well as other scholars continue to analyse the pervading influence of Hanse: What was the nature of the medieval Hanse: a trading network, a league of cities, an ‘organization’, a ‘proto-EU’ or a colonial structure? A form of cultural dominance, with its city culture, language, and its legal system? Can the Hanseatic legacy be seen as a common legacy?

The Sea as a Unifier

Whatever challenges we face in interpreting our common past and in framing our Baltic identity, one thing remains unchanged: all the interactions and exchanges were made possible due to the existence of the Baltic Sea. At the time of the Hanseatic League the sea was treated as a limitless source for fisheries, and a surface to be crossed to reach a destination, to promote trade interests, and to exercise maritime power. People lived by the sea, on the sea and off the sea, using its connection to inland waterways, such as rivers and canals, for transporting goods to and from non-coastal cities, such as Kraków or Toruń. This, to a certain extent, still holds true today. According to a book published by the Baltic Development Forum in 2011, Prof Bernd Henningsen wrote:

“Lennart Meri’s pragmatism said it best: the Baltic Sea, the Sea itself, is the substantive element of the region; a branding strategy based on this fact is always true. If nothing else, there’s room for a history of longing for the sea; from such a history, were it ever written, one could develop a Baltic Sea identity that would be more convincing than a history of the adventures (or misadventures) of clever Hanseatic merchants.” (p. 61 of ‘On Identity – No Identity. An Essay on the Constructions, Possibilities and Necessities for Understanding a European Macro Region: the Baltic Sea’)

While it is possible that the Sea itself can be a unifier in these difficult times, the challenges faced in modern and postmodern times are of a very different nature.

Seals as a litmus for the health of the sea

As top predators, seals are a crucial part of the Baltic ecosystem. Water eutrophication, hazardous substances, noise pollution, habitat loss, and the by-catch of seals in fishing gear have always put an enormous pressure on the Baltic fauna. While in some areas of the Baltic Sea the seal population has rebounded, in others they need to be protected through awareness raising campaigns, alternative fishing gear, and special protection zones designated in their key resting and breeding areas. While the concentration of some hazardous substances, such as DDT or PCBs, has decreased substantially, there are new environmental toxins, known as chlorinated paraffins, entering the marine ecosystem and harming the marine mammals. Found in plastic, paint or rubber, they can disrupt the hormonal system. Conflicts between seals and conservationists on the one hand, and tourism, maritime transportation, coastal fisheries and the hydro-technical construction sector on the other, are by no means rare.

Sick, injured or orphaned, the mammals face multiple threats ranging from injuries, by-catch, habitat loss, through toxic chemicals, marine pollution, and climate change, to conflicts with coastal fisheries. Both we, humans, and Baltic seals are in the same boat: an unhealthy ecosystem is a less resilient ecosystem, and new groups of chemicals threaten us all across the board. It is impossible not to notice two things: 1) the threats are posed mainly by human activities; and, 2) these activities threaten both humans and animals alike.

All of the things mentioned here, from the Hanseatic League and the role of the Baltic Sea and rivers in its development, or the Nord Stream pipeline explosion and its wide-ranging consequences for people, animals and the whole life-sustaining ecosystem, point to how the Baltic Sea seals and their condition could be seen as a litmus test for our human and ecosystem health.

Ecocultural identity

Human actions, be they social, political, cultural, economic or military, do not occur in a vacuum, but are embedded in larger ecosystems. I would argue that our human identities are, first and foremost, both ecological and cultural in nature, like two sides of the same coin, distinct but not separate. In other words, sociocultural aspects of our identities are always inseparable from the ecological ones, which shows how deeply interconnected humans are with the more-than-human world. Although ecocultural identity is a very old concept, it has largely been erased from academia. However, such an ecocultural perspective on the foundations of Baltic identity holds a lot of promise; it does not provide us with ready-made answers or solutions, but rather points toward certain directions along which to look, and creates a supportive space for reimagining our (human) relation to ourselves, other people, animals, and life-supporting ecosystems. While people with their cultures, histories and herstories, economic and political systems are embedded in the biosphere (all life-supporting ecosystems), their relations to the more-than-human-world manifest themselves in different system-bound and culture-specific ways, shaped by their values, beliefs, myths, stories, and narratives.

Baltic Sea beaches are indicative of how fluid, non-linear and overlapping the nature of boundaries is between the land and the sea, people and animals, saltwater and freshwater ecosystems, nature and culture. This fluidity is mirrored in multi-level governance, cross-sectoral activities, and trans-boundary threats – they all testify to the highly relational nature of our human and more-than-human existence. Our fate and the seals’ are highly interconnected through the food chain and the ecological state of the Baltic Sea and the rivers flowing into it.

Ecocultural identity is not only about perceiving or accepting the interconnections between human and more-than-human groupings BUT also about acting and making informed choices. It points toward certain directions but doesn’t provide ready-made solutions. Ecocultural identity opens space for reimagining our (human) relation to the more-than-human world (flora, fauna, and the physical environment). In other words, it is an underlying concept of inclusive, non-normative and cross-boundary nature, to be rediscovered rather than invented. Every social and cultural identity is ecological. However, there is unfortunately no guarantee that embracing this concept will automatically result in sustainable policies and actions. It’s not about saving the seals or the Baltic Sea for that matter – it’s about saving ourselves from our flawed human perception of being separate from the Baltic Sea, with its unique fauna and flora. It’s about embracing Sylvia Earle’s cry that “[e]veryone, everywhere is inextricably connected to and utterly dependent upon the existence of the sea”.

This contribution has been inspired by the topics and events of the 2023 CBSS Summer University, held in Gdańsk, Gdynia, and Hel (Poland, 16-25.09.2023).

Further reading:

- Bernd Henningsen, On Identity – No Identity: An Essay on the Constructions, Possibilities and Necessities for Understanding a European Macro Region: The Baltic Sea (Copenhagen: The Baltic Development Forum, 2011).

- Tema Milstein and José Castro-Sotomayor (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Ecocultural Identity (2020).

- Stephen Jay, 'The shifting sea: from soft space to lively space', Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 20, 4 (2018), pp. 450-467.

- Sylvia A. Earle, The World is Blue: How Our Fate and the Ocean’s Are One (Washington D.C.: The National Geographic Society, 2009.