The History of the Baltic Sea Region and Contested Identities

The concept of the Baltic Sea Region challenges the idea of history as being solely a national narrative. Far from being fixed, contested Baltic identities have been used instrumentally to further political goals, or to capture the zeitgeist of an era. The region cannot be not objectively and geographically defined, but is a changing story that reflects the needs and challenges of the times in which it is created. Whether Polish identity aligns with the Baltic Sea region or not is a good example of this flux.

Looking beyond the history of individual nation states

Most of us, whose first contact with history as a discipline was in school, are used to thinking about it in terms of national history: We were taught the history of Poland, Sweden, Germany, etc. There are, however, different ways to approach the past, and the history of the Baltic Sea region (BSR) is one way to do that. Especially since the fall of communism in Eastern Europe and with advancing globalisation, borders in Europe became less impenetrable and the mobility of peoples, ideas, and goods increased. At the same time, arguments appeared about the decreasing role of the nation state, which was expected to be replaced – eventually – by other forms of governance, both higher and lower: local, regional, trans-regional and global.

In research, including history, this was reflected in the appearance and growth of approaches focusing on transfers, exchange, connections, and circulations, which – it was felt – could better depict this new kind of world than traditional political and economic histories of nation states. Historians also became increasingly interested in writing histories of other units than the nation state – including regions. Sea regions in particular, which already had a tradition spanning back to Fernand Braudel’s The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II (first published in 1949), emerged as the epitomes of interaction and transfer, of networks connecting shores, cultures, and port towns. With their connections to world and global history, sea regions became an especially fitting topic for regional history.

Constructing the Baltic Sea Region

The Baltic Sea Region fit very well into these trends, having been cut in half by the Iron Curtain for four decades and reunited with the fall of the Soviet block. (See Olle Wæver for more on this.) The metaphor of a moat and connecting link was an attractive way to express the optimism for Baltic Sea regionalism that was the spirit of the time. The Cold War was imagined as a time when the sea was transformed from a space that connected people into an impassable moat – an image depicted in Klas-Göran Karlsson and Ulf Zander’s introduction to the 2000 book Östersjö eller Västerhav? Föreställningar om tid och rum i Östersjöområdet (‘The Sea to the East or the West? Baltic Sea or the West Sea? Perceptions of time and space in the Baltic Sea region’). Now that the moat was gone, it was again possible to imagine it as a space of connections and transfers, for which a common history could be written, and importantly, a new, regional identity constructed based on this common history. In such historical narratives, the Baltic Sea Region was often defined not with strict geographical criteria, but as an arena of historical processes (e. g. networks of trade, structures of communication across the sea, the spread of ideas such as Christianity and Reformation, medieval colonisation, etc.). Characteristic of these definitions was the concentration on positive processes of peaceful cooperation and exchange, while nationalism was blamed for the destructive twentieth-century wars.

Some examples of Baltic Sea Histories include:

-

David Kirby, Northern Europe in the Early Modern Period: The Baltic World 1492–1772 (London: Longman, 1990).

-

David Kirby, The Baltic World 1772–1993: Europe’s Northern Periphery in an Age of Change (London: Longman, 1995).

-

Matti Klinge, Itämeren Maailma [The Baltic Sea World] (Helsinki: Otava, 1995).

-

Kristian Gerner, Klas-Göran Karlsson, and Anders Hammarlund, Nordens Medelhav: Östersjöområdet som historia, myt och projekt [The Nordic Mediterranean: The Baltic Sea region as history, myth and project] (Stockholm: Natur och kultur, 2002).

-

Michael North, Geschichte der Ostsee: Handel und Kulturen [The history of the Baltic Sea: trade and cultures] (München: Verlag C.H.Beck, 2011).

For and against Poland as a Baltic Sea country

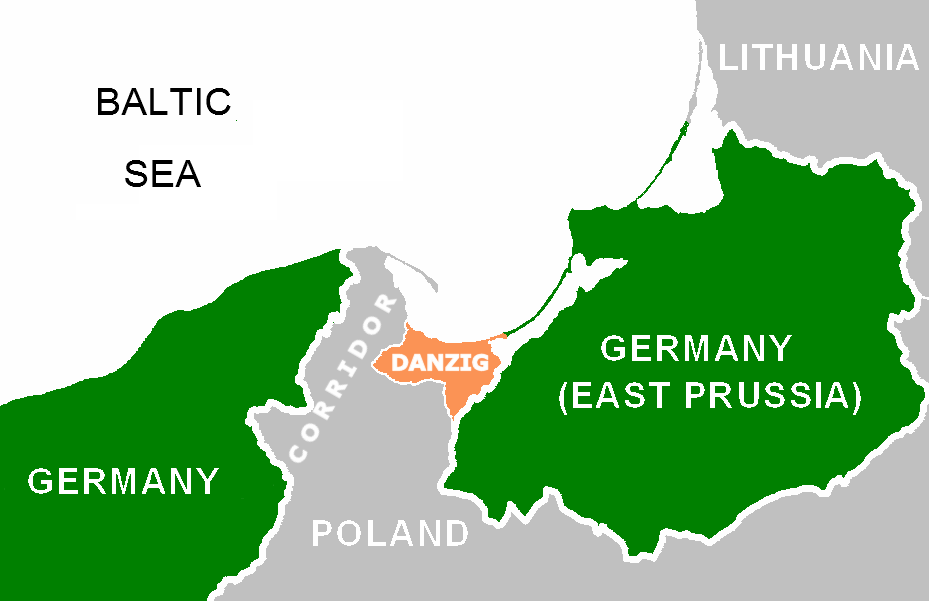

However, the construction of a region and regional identity around the Baltic Sea is not that simple. Determining who should and should not belong to the BSR, who was Baltic and who was not, was contested throughout the twentieth century. For example, the Baltic identity of Poland in the interwar period was both challenging to construct internally and questioned externally. In particular, in Germany, where many called for a revision of the Versailles borders that had left parts of the former German territories in the east to Poland, arguments arose that Poles – and Slavs in general – were land people by nature, and therefore supposedly did not need access to the sea, nor did they know what to do it when it was granted to them. Internally, the dearth of Polish maritime traditions led to a lack of understanding of, and identifying with, the sea, which was much discussed by historians such as Marian Małowist and Janusz Tazbir later in the twentieth century. Stanisław Srokowski, the director of the Baltic Institute, a research institution founded, among others, to remedy this through research on the Baltic Sea, wrote in 1926 that:

“the Polish sea shore in our everyday concepts [was] still some distant borderland, not the country’s lungs and indispensable organ of its free existence.” (Page 3, Instytut Bałtycki i jego zadania [The Baltic Institute and its tasks], 1926, translation by the author).

The same Baltic Institute questioned Germany’s and Russia’s/USSR’s belonging to the BSR, as not being “predominantly Baltic in their orientation.” (A quotation taken from ‘Baltic and Scandinavian Countries: A survey of the peoples and states on the Baltic with special regard to their history, geography and economics' 4, no. 3 from 1938). The Baltic Sea identity was the object of political struggle, in this case connected to the question of access to the sea via the region of Pomerania and the so-called Danzig corridor which the two nations – Poland and Germany – clashed over throughout the interwar period.

This case of contested Baltic identity shows that regional identities – and historical concepts which they are often based on – can be used instrumentally, to further political goals, back up ideological arguments and territorial claims. At other times, as was the case in the post-1989 enthusiasm for the region, regional identities can be a reflection of the zeitgeist and the hopes it engenders. The historical narrative of the BSR does not exist as an “objective” take on a certain geographically defined area, but is rather a changing story that reflects the needs and challenges of the times in which it is created. The question remains open: What kind of regional historical narratives and regional identities will the current situation in the BSR bring?

Further reading:

- Janusz Tazbir, Rzeczpospolita szlachecka wobec wielkich odkryć [The Polish nobility in the face of great discoveries] (Warszawa: Wiedza Powszechna, 1973).

- Jörg Hackman, Past Politics in North-Eastern Europe: The Role of History in Post-Cold War Identity Politics. In Marko Lehti and David J. Smith (eds.), Post-Cold War Identity Politics: Northern and Baltic Experiences (London: Routledge, 2003), pp. 81-82.

- Klas-Göran Karlsson and Ulf Zander, eds., Inledning [Introduction]. In Östersjö eller Västerhav? Föreställningar om tid och rum i Östersjöområdet [Baltic Sea or North Sea? Perceptions of time and space in the Baltic Sea region] (Karlskrona: Östersjöinstitutet, 2000).

- Kristian Gerner, Centraleuropas återkomst [The return of Central Europe] (Stockholm: Norstedts juridikförlag, 1992).

- Marian Małowist, Kraje bałtyckie i wczesna europejska ekspansja zamorska [Baltic states and early European overseas expansion]. In Antoni Mączak, Hanna Zaremska, eds., and Tadeusz Duliński (trans.), Europa i jej ekspansja XIV–XVII w [Europe and its expansion in the 14th-17th centuries] (Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 1993), pp. 146-56.

- Marta Grzechnik, Regional Histories and Historical Regions: The Concept of the Baltic Sea Region in Polish and Swedish Historiographies (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2012).

- Olle Wæver, From Nordism to Baltism. In Sverre Jervell, Mare Kukk, Perrti Joenniemi (eds.), The Baltic Sea. A Region in the Making (Karlskrona: Baltic Institute, 1992), pp. 26-38.

- Stefan Troebst, '‘Intermarium’ and ‘Wedding to the Sea’: Politics of History and Mental Mapping in East Central Europe', European Review of History: Revue européenne d'histoire 10, 2 (2003), pp. 293-321.