The Baltic Sea Region

The Baltic Sea Region

The Baltic Sea and the Baltic Sea Region are very relevant to the Nordic countries, not only culturally and historically, but also from a geopolitical, environment and security perspective. In this theme page, you can find articles, films and podcasts about the Baltic Sea Region.

What is the Baltic Sea region?

The Baltic Sea stretches from St Petersburg in the east, to Denmark in the west. It stretches from far in the north, up the Gulf of Bothnia between Finland and Sweden, and down to Germany and Poland in the south. But the Baltic Sea Region can be defined in many ways and it is often considered much wider than simply the countries that lie on the coast of the Baltic Sea itself. The Council of Baltic Sea States’ list of members also includes countries with no physical connection to the Baltic Sea at all: all of the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden), Poland, Germany, the three Baltic countries (Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia) and the EU, and Russia and Belarus were also included until 2022. The region can also be defined by water, that is, it encompasses the sea itself and the land influenced by the drainage basins which are connected to the Baltic Sea in some way, as well as the rivers that flow into it. By this definition, the region would also include countries like Ukraine, the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

While some may use strict geographical criteria to define the Baltic Sea region, others take the view it cannot be seen as a physical entity, but it is an idea which has blossomed at different times in history. For example, there are also countless political and historical ways to define a region, as there are equally many complex and contested identities within it. Some of the different ways of defining the Baltic Sea region are discussed in the podcasts What is the Baltic Sea Region and how has it changed since the invasion of Ukraine? and Regionalisation and the Baltic Sea Region. That said, what most of the materials we have on nordics.info on the Baltic Sea region have in common is that they tend to challenge the conventional understanding of history as a national narrative.

Historical connections crisscross the Baltic Sea region

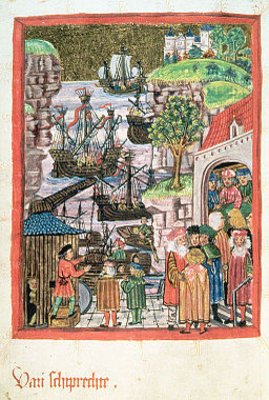

The Hanseatic League is most often cited when talking about the historical connections between the countries around the Baltic Sea. The League or Hanse was a medieval association of merchants from Northern Europe which shaped trade relations in the area (and arguably beyond it) from the 12th to the 16th century. It was a trade federation or a league of cities with sophisticated methods of organization and a lot of power, culturally as well as economically. Hanse is touched upon in Marta Skorek’s article The Baltic Sea and Ecocultural Identity, and again in the podcast What is the Baltic Sea Region and how has it changed since the invasion of Ukraine?

The most recent coming-of-age period for the Baltic Sea region was arguably the 1990s and the post-Cold War zeitgeist in Central and Eastern Europe. Newly found freedom paved the way for alternative regional constellations, including the Baltic Sea region which stretched across both sides of what had been the Iron Curtain. Regional institutions, such as the Council of the Baltic Sea States and the Union of Baltic Cities, were founded during this period (in 1992 and 1991 respectively). Saara Mildeberg talks about the landscapes of northeastern Estonia and how they reflect the country’s and region’s history, particularly during and after the Cold War, in the podcast The Baltic Sea Region and Estonian Heritagescapes.

It should be remembered, however, that the HELCOM countries had been working together across this divide since the 1970s. HELCOM is an intergovernmental organization bridging policy and science on matters related to the environment of the Baltic Sea, and began in 1974 with the Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea. The Convention seeks to protect the Baltic Sea from all sources of pollution from land, air and sea, as well as to preserve biological diversity and to promote the sustainable use of marine resources, and has 10 signatories (Denmark, Estonia, the European Union, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia and Sweden).

There are of course a plethora of other historical connections, including dynastic links (such as the dispute between the Polish and Swedish Vasas over the Swedish throne), the changing of borders, and the swapping of territory throughout the ages. These complexities are touched on throughout much of the material in this theme page and generally on nordics.info. Pertinent examples here include:

- An overview of the complex relationship between Poland and Ukraine is given in the podcast Regionalisation and the Baltic Sea Region.

- The relationship between Denmark and Belarus, and Belarus and Europe in general, is discussed in the film Critical Borders, Denmark and Belarus, and it underlines that it was not until 2022 that Belarus was known as such in Denmark and not ‘Hviderusland’ (White Russia).

- Our article Finland in (popular) geopolitics gives an overview of Finnish history from the early 20th century until now.

- Ingria and the Ingrian Finns is about the isthmus between the Baltic Sea and Lake Ladoga, connecting modern-day Finland with modern-day Estonia and the seventeenth century Finnish-speaking settlers there and their descendants. While today this region is dominated by the city of St Petersburg, Ingria has seen numerous invasions, annexations and changes to state boundaries, reflecting the major historical events of early modern Northern Europe over the last 400 years.

- We have several articles about the Åland islands found in the middle of the Baltic Sea between Finland and Sweden, and the article The Legal Basis of Åland’s Demilitarization and Neutralization reflects key security issues in the area of the Baltic Sea for the last 100 years or more.

(Please do note, however, that we do not provide a comprehensive overview of Baltic Sea history, which can alternatively been investigated further through the free online course Baltic Sea History: New Perspectives on the History of the Baltic Sea Region.)

Key causes bringing countries together

The climate is an example of a key cause which brings countries influenced by the Baltic Sea region together as regional solutions are necessary to combat environmental degradation. Other key issues include the prevention of human trafficking and child protection, taken up by the Council of Baltic Sea States for example, and connectivity within the region and increasing prosperity, taken up by the European Union. The EU’s Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region (EUSBSR) was instigated in 2009 and was the first of four macro-regional EU strategies, which is explained in the film on The Ocean and the Baltic Sea Region.

The environmental picture is much more complex now that there are additional threats due to geopolitical tensions and military conflicts. Incidents like the Nord Stream pipeline explosions in 2022 exacerbate environmental concerns, releasing hazardous materials into the sea and increasing greenhouse gas emissions. Moreover, the Baltic Sea’s complex marine ecosystem is highly vulnerable to disturbances, including those caused by warfare, pollution, and climate change. In response to these pressures, Marta Skorek’s article The Baltic Sea Region and Ecocultural Identity advocates for reimagining human relations with the Baltic Sea and its ecosystems, and emphasises the urgency of sustainable policies and actions to ensure the well-being of both humans and the environment.

Pan-national regions and macro-regional strategies

Macro-national regions can set the stage for cooperation and exchange. The Nordic region and the Baltic Sea region can be compared and contrasted as two pan-national regions that are both side by side as well as overlapping, and these can also be compared with other pan-regional areas around the world, such as Latin America or the Balkans. [Peter Stadius from the University of Helsinki talks about pan-nationalism in this film (forthcoming).] The countries within a region (at least seen from outside) have to have certain things in common to be considered members of a particular family of states.

In the case of the Nordic countries, similarities that are often cited include history, language, politics, religion and culture, arguably key aspects which bind them together and make cooperation easier. (You can learn more about how regions come about in the podcast Can we identify with regions like the Nordics or the Baltic Sea region?). Each Nordic country is also committed to regional bodies which oil the wheels of cross border cooperation, namely, the Nordic Council and the Nordic Council of Ministers (founded in 1952 and 1971 respectively).

The Baltic Sea countries are arguably more geographically dispersed and diverse, so while it is possible to find a similar list of reasons that bind them together, the region is more diffuse and the regional institutions are arguably less established and well-resourced than those in the Nordic region. These types of comparisons and the benefits and challenges of these pan-national regions and regional institutions are discussed in several podcasts including Can we identify with regions like the Nordics or the Baltic Sea region?, What is the Baltic Sea Region and how has it changed since the invasion of Ukraine? and Regionalisation and the Baltic Sea Region.

The Baltic Sea region and the Nordic region often look different from the outside than they do from the inside, and these different narratives feed into one another. Karolina Drozdowska’s article on Comparative Literature and Decoding the Complexities of the Baltic Sea Region advocates understanding narratives as interconnected and culturally constructed, and this view can help decode reality and identify manufactured narratives with specific agendas – like those emanating from Putin’s Russia, which deeply affect the Baltic Sea region in 2024.

The boundaries of the region

The boundaries of the Baltic Sea region are often defined by historical events and concepts and therefore fluctuate. In the article How Nordic is Estonia?: An overview since 1991, the writer explores Estonia looking towards the Nordics in various walks of life. Defining where boundaries lie can be challenging and can also be used instrumentally to further political goals, back up ideological arguments, or make territorial claims. The historical narrative of the Baltic Sea region is a changing story that reflects the challenges of the times in which it is created. In her article on the History of the Baltic Sea region and Contested Identities, Marta Grzechnik looks back at discussions in the interwar years about whether Poland, Germany and Russia/USSR could be conceived of as ‘Baltic’: Could, for example, Poland belong to the Baltic Sea region as Poles were, some argued, land people by nature with few maritime traditions? The absence of Russia and Belarus around the table at the Council of the Baltic Sea States due to the invasion of Ukraine has arguably brought the remaining countries closer together, enhancing regionalization in some ways, and diminishing it in others.

You can find out more about the Baltic Sea region by browsing the links below, or the borders of the Nordic region by going to our theme page on The Borders of the Nordics.

Articles to do with the theme the Baltic Sea Region on nordics.info:

Further reading

- Bernd Henningsen, On Identity – No Identity: An Essay on the Constructions, Possibilities and Necessities for Understanding a European Macro Region: The Baltic Sea (Copenhagen: The Baltic Development Forum, 2011).

- Damian Szacawa, Kazimierz Musiał, eds., 'The Baltic Sea Region after Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine', Institute of Central Europe, IEŚ Policy Papers 11/2022.

- Jörg Hackman, Past Politics in North-Eastern Europe: The Role of History in Post-Cold War Identity Politics. In Marko Lehti and David J. Smith (eds.), Post-Cold War Identity Politics: Northern and Baltic Experiences (London: Routledge, 2003), pp. 81-82.

- Karolina Drozdowska, 'The Others from Across the Sea — Eastern Europeans and Eastern Europe in Modern Norwegian Literature', Archiwum Emigracji 28 (2021), pp. 292-305.

- Olle Wæver, From Nordism to Baltism. In Sverre Jervell, Mare Kukk, Perrti Joenniemi (eds.), The Baltic Sea. A Region in the Making (Karlskrona: Baltic Institute, 1992), pp. 26-38.

- B. M. Russet, 'Delineating International Regions', In: J. D. Singer, Ch. F. Alger, eds, Quantitative International Politics: Insights and Evidence, Free Press: New York (1968) pp. 317-352.