Views of a Nordic Past

Views of a Nordic Past

Historical ties are a key part of the Nordic region’s interconnectedness. The region now consists of five sovereign states, including three autonomous territories, the Faroe Islands and Greenland (Denmark) and Åland (Finland). But this was not always the case. There have been many different constellations of unions, dual kingdoms and other alliances between the Nordic countries - and equally many conflicts and wars. The narratives of these historical periods are naturally very different depending on the perspective with which they are viewed.

Christian II ruled Denmark and Norway from 1513 to 1523, as well as Sweden for some of that time. In Sweden, he is remembered as the instigator of a bloody massacre, whereas in Denmark, he is lauded as a supporter of the poor against the aristocracy.

Another important Danish King, Christian IV, who reigned from 1588-1648, perpetuated narratives that were useful to him. He put it about that Sweden was a vassal kingdom where its king only received power from the Danish monarch and was subordinate to him.

In the Second Schleswig War ('1864'), Denmark lost 40% of its population to Prussia and Austria, which has since played a big part in the creation of modern-day Denmark and the national narrative of its people. The relationship between Denmark and Germany has been highly affected by this ever since, especially during the early 20th century. A plebiscite in 1920 saw Southern Jutland – or at least a significant part of what Denmark had lost in 1864 – returned to Denmark. Watch two films about drawing the German-Danish border, the vote in Felnsburg in 1920 and posters and propoganda from 1920 (in Danish with English sub-titles). The plebiscite also proved important for the other Nordic countries as it meant that Germany arguably took over from Sweden as Denmark's main enemy in the period that followed - hear more about the history of the Danish-German border in an interview researcher Caroline Weber.

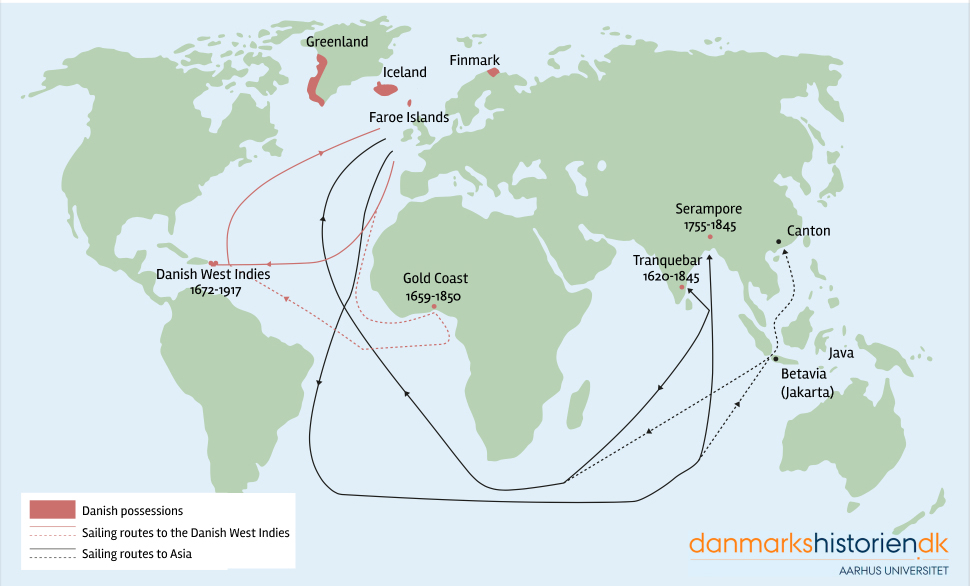

Colonialism and its legacies: Rewriting history

MAP: Danish Tropical Colonies and North Atlantic Monopoly Trade Areas, sailing routes between Denmark and the tropical colonies between 1700-1800. (Edited from the Danish version). Permission for use kindly granted by danmarkshistorien.dk.

Overshadowed by British and French Imperialism, the small-scale colonialism of some of the Nordic countries can all too easily be downplayed. However, the article ’The colonialism of Denmark-Norway and its legacies’ tells us that Denmark-Norway engaged in a variety of colonial activities throughout the world from the 17th century, which still have legacies today. Although perhaps on a lesser scale compared to other larger colonial powers, its colonalism was characterised by different contexts - some of them brutal - in the Caribbean, West Africa, India and Greenland. While the Danish, documented perspective has long been part of the history books, alternative perspectives on colonialism continue to be told. Watch this film on postcolonialism, read a quick read on the 1878 Fireburn uprising in the Danish West Indies, or listen to this podcast to find out more: Denmark: Uncovering the Legacies of Nordic Colonialism with Lill-Ann Körber.

That perceptions of colonialism have changed over time can be illustrated by many things. For example, the response to US President Donald Trump suggesting that the US buy Greenland in 2019. Read the article Buying Greenland: Trump, Truman and the Pearl of the Mediterranean which traces the geopolitical interest in Greenland back to Truman’s era in the 1940s. The article the Danish decolonisation of Greenland, 1945-54 looks particularly at the UN's role and the relationship between Denmark and Greenland in a time when independence movements were taking place all over the world (also available as a podcast in Danish and English).

PICTURE: Elsa Laula Renberg (1877-1931), a prominent Sámi politician. Photo: By Unkown - Saemien Sijtes fotoarkiv, Public Domain

The Sámi population who inhabit the northern Scandinavian pennisula - as well as parts of Russia - can also be considered a colonised people. Their original livelihood of reindeer-herding and their culture has been threatened by both laws and the encroachment of the dominant culture in Norway, Sweden and Finland. You can hear more about this in an interview with Lill-Tove Frederiksen, "we won't be silenced" - language and literature, or learn more about about Sámi culture, including Yoiking, handicrafts, language and literature (the latter is also available as a podcast in Finnish and English).

Colonial legacies in Iceland also have modern manifestations. Kristin Loftsdóttir's article, ’"I’ve come to buy Tivoli”: Colonial desires and anxieties in Iceland in a new millennium’ traces the interest of Icelandic 'business Vikings' in Danish business and property in the 2000s back to the time of Danish rule. An overview of the History of Iceland can be a useful reminder of the different ties between Denmark and Iceland. Similarly, in the podcast Iceland: Uncovering the Past in Nordic literature, Gunnþórunn Guðmundsdóttir gives an account of how the rewriting dominant historical narratives is important to understand what lies behind past and present Nordic culture and behaviours.

Nordic (hi)story-telling

PICTURE: The events immediately after the German invasion of Norway in 1940 are told from the perspective of King Haakon VII and the Norwegian Royal Family in the 2016 film 'The King's Choice'. Photo: Wikimedia, Fair use.

Throughout history, historical story-telling has often been used for particular reasons, to sell a product or a dream, to advance a particular ideology or to tear one down. Niels Kayser Nielsen’s article ’The uses of Nordic history’ explains that we all use history selectively – or make use of the past.

While myth and stories of heroes, gods and goddesses may nowadays be commonly perceived as ’fiction’, in earlier epochs the boundaries between truth and fiction were perhaps more fluid. Read, for example, about Danish national romanticism in art in the 19th century, when depictions of Valkyries and characters from the Icelandic sagas were used to incite national feeling.

Folklore is a phenomenon found in all cultures and can be seen as a popular appropriation of the past. Falling under the umbrella of what is now called ‘intangible cultural heritage’ by UNESCO, it encompasses everything from Finnish improvisational rap and medieval eddic poetry to internet memes or wearing a crown of candles on St Lucia’s day.

When we visit museums, we are presented with a particular view of the past, as can be seen in many of the museums in the Nordic countries. Our ideas of the past are shaped by many things: a mish-mash of images and stories told by our parents or learnt at school; events portrayed in novels, the TV or through advertising and political messaging; as well as – importantly – where we choose to look and our own opinions. Even our very identities are bound up with history, seeing as they are informed by our historical consciousness and our relationship to our own heritage - whether this is local, national or transnational. Memory studies takes a different approach to that of seeking the ‘objective truth’ of the past, which is usually seen as the aim of academic history. How the past is interpreted in different ways is explored in the following podcasts (pending forthcoming publication): ’Shaping a Nordic Past: Fact, Fiction or Simply Politics?’ and ’History-makers or money-makers?’.

Nordic connectedness in today’s world: a key example of the use of the past

More recent history arguably binds the Nordic region, not least the dominance of the social democratic movement throughout much of the twentieth century, which has had a significant influence on the Nordic countries. Social democratic parties in most of the Nordic countries were closely associated with the trade union movement and their aims included full employment and the promotion of social justice and equality. here were different political parties and manifestations in each of the Nordic countries; these types of aims were spearheaded by the Labour Party in Norway which dominated the political stage from the mid-1930s until the late-1960s and was seen as a Golden Age for social democracy.

PICTURE: The building where Norwegian Labour Party headquarters is housed in Oslo, built in 1935. Photo: Emmanuel Wald. Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0.

This period – as well as earlier periods in some instances - was also supposedly characterised by feminism, the concept of folkhem and a strong civil society, for example. These are all narratives that bind the Nordic countries together as a region in a collective history, although this altogether 'rosy' picture has also been undercut by numerous scholars.

The political influence of social democracy is generally considered to have waned from the 1990s onwards, but social democratic parties in the respective Nordic countries remain significant as they have sought to adapt to new political and social challenges. The Nordic Model and what are considered to be key aspects of the Nordic region – such as cooperation, language and culture – have led to the region having a persistent presence in the European imagination. This can be exoticised to a greater or lesser extent, as explained in this article about images of the Arctic. As Peter Aronsson argues in The power of Nordic culture to transform Nordic history, many of these key aspects of the Nordic region have provided legitimising grounds for events and movements throughout history - and today’s world is no exception. In the 21st century, for example, he argues that Nordic culture could be viewed as legitimising a revised cultural contract between liberal individualism and strong state intervention.

Aspects which unite the Nordic countries can be seen from a variety of perspectives, but Aronsson warns that the path of Nordic culture needs to be trodden with care: It can encourage racism and anti-democratic forces and uncertainty. In spite of their image as sound economies and consensual democracies, the Nordic countries, especially Finland, have a long history of populist movements, which is explored in Democracy in the shadow of populism - a Nordic way out?. The history of Nordic populism has been described as a process moving from political dissatisfaction with tax issues during the 1970s to discontent with refugee and migration policy in the 1980s, the 1990s and the early part of the 21st century.

The Vikings and racialising the Nordics

The Vikings are of course a good example of the use of the past, being as they are invoked in all sorts of contexts, from underwear and hand-dryer brands to the fantasies of business and management leaders and onwards to home DNA testing kits and their seductive promise of ”Viking heritage”. In the podcast, The Vikings and Capitalism, medieval historian from Aarhus University Richard Cole explores why the Viking era is ‘up for grabs’, and explains why and how some business gurus have latched on to truths, half-truths, and fallacies about the Vikings.

PICTURE: Reconstruction of the Birka warrior woman with a high status. Clothing details are based on material from the Birka chamber burials and on the contemporaneous graves from Moshchevaya Balka in the North Caucasus (Knauer 2001, drawing by Tancredi Valeri). Photo: From the article 'Viking warrior women? Reassessing Birka chamber grave Bj.581'. (Non-commercial use permitted © Antiquity Publications Ltd, 2019).

Essentialist ideas about the Vikings repeated in popular culture can perpetuate particular racial ideas about Nordicness. These ideas are often appropriated by certain ideologies, including fascist and racist groups. Interestingly, the female Viking has taken on a particular resonance - gender equality is inextricably linked to the Nordic brand has been used by right-wing political actors, as well as extremists, in support of anti-immigrant and racist agendas. Read more about this in the article Pop culture, Vikings and historic Nordic gender equality?

Particular racialised views of the past are not only to do with the Vikings in the Nordic countries, but they pop up in all manner of contemporary settings. For example, some of the most beloved figures in Nordic children’s literary classics from the 20th century are rooted in narrow-minded caricatures. The article Racism in classic pieces of Nordic children's literature suggests that racial prejudice can be so subtly embedded in many older pieces of literature that even contemporary readers are blinded to it. The discussion surrounding the republishing of some of these controversial books provides interesting perspectives on contemporary views of race and racism. It is important to consider how the past is used in the present and how it is made meaningful in the Nordic societies.

The Vikings and Nordic history and culture is also used as inspiration for the gaming industry, which is explored in the podcast Gaming the Nordics with three researchers from the Helsinki Game Research Collective. Nordic regionality can be expressed through different applications of game, game design and play, and it is used in different ways (such as, counterfactual uses of history, reflecting the same darkness as in Nordic Noir, or using myth and nostalgia) and in different contexts (such as, representations of cultural hegemony, or using history and heritage).

-

Read more on @nordics.info!

Further reading

- Aronsson, Peter & Lizette Gradén, (eds.), Performing Nordic heritage - Everyday practices and institutional culture (Surrey: Ashgate, 2013).

- Cauvin, Thomas, Public History - A Textbook of Practice (New York: Routledge, 2016).

- Kalela, Jorma, Making History - The Historian and Uses of the Past (New York: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2011).

Links

- Aarhus University's research project: Uses of the Past

- Danmarkshistorien.dk

- Nordic Civil Societies project webpage at The University of Oslo

- norgeshistorie.no