Buying Greenland? Trump, Truman and the 'Pearl of the Mediterranean'

In the summer of 2019, the Trump Administration voiced an interest in buying Greenland from Denmark. The historical background for this stretches at least as far back as a case brought by Norway at the International Court in 1933 when it was decided that Denmark had full sovereignty over Greenland. Since then, Danish governments have engaged in reformulations and re-negotiations with respect to Greenland’s sovereign rule, including the 1979 home rule agreement and self rule in 2009. It is arguable, however, that the US had de facto sovereignty for periods of the 20th century. For example, a defense pact in 1941 allowed the US extensive rights to military bases in Greenland in exchange for military protection while mainland Denmark was occupied by Germany. This led to the Truman administration making an actual bid to purchase the world’s largest island in 1946. During the Cold War, Denmark relied on the US to defend Greenland. While today, after obtaining self rule in 2009, it is recognized that Greenland has the right to become independent if it so wishes, questions of its sovereignty remain. These were highlighted by the recent diplomatic spat between Trump and the Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen, indicating that the sovereignty issue will continue to be contested and pose a considerable challenge even for a fully independent Greenland of the future. Greenland has been and continues to be a vital strategic asset, not least to the US - and perhaps even more so due to the possible effects of climate change.

Introduction: the strategic value of Greenland

Today, delegations from all over the world, state representatives as well as private, queue up in Nuuk to position themselves as prospective partners and contractors for the future bonanza of resources that Greenland seems to offer. What triggers the interest is Greenland’s possession – expected or certified – of vast deposits of raw materials, among them oil and a number of rare and strategic minerals and soils, in combination with the fact that effects of the ongoing global climate change will make it much easier to access these materials. Part of this increased accessibility is linked to the vision that climate change may soon make the so-called Northern Sea Route, connecting the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans through the North Arctic, a reliable and (partly) ice-free waterway. If this happens, we may indeed come to conceive of Greenland as the ‘Pearl of the Mediterranean' (Middelhavets Perle).

![Front cover of the book 'Grønland-Middelhavets perle' [Greenland: The Pearl of the Mediterranean]](/fileadmin/Nordics.info/Buying_Greenland_Pearl_of_the_Mediterranean_lge.jpg)

Greenland as 'The pearl of the Mediterranean' was a term coined by Paul Claesson in his 1983 book about Greenland's strategic place in the global arms communication and monitoring systems ('Grønland-Middelhavets perle' [Greenland: The Pearl of the Mediterranean] (Copenhagen; Vandkunsten, 1983)). Photo: Courtesy of Forlaget Vandkusten.

For military analysts and strategists – and for some politicians too – Greenland has possessed this strategic value for some time already. And, again, interest has apparently come to the fore with the Trump administration’s recent scheming to buy Greenland, which was made public in August 2019. In the new power struggle over the Arctic, intensified by the prospect of climate change, Greenland’s strategic importance is considered vital both as an asset to control for its own purposes, but also as an area, especially in the American view, to which competitors and adversaries should be denied access.

This logic was already at work during the Cold War and even the Second World War. Greenland acquired a pivotal position in the nuclear arms race as the progress in both nuclear bomb technology and in connected delivery technology (the development of long-range bombers and missiles) in the postwar period greatly increased Greenland’s importance for US defense and military strategy. Already in 1941, the Danish ambassador in Washington, Henrik Kauffmann, signed a defense pact allowing the US extensive military base rights in Greenland in exchange for military protection while mainland Denmark was occupied by Germany. Once there, the American military never left, although military rights and defense prerogatives have changed somewhat over the years and, like today, the American interest in buying Greenland was specifically tabled in 1946-47 when the Danish Government wanted to terminate the 1941 agreement.

This logic was already at work during the Cold War and even the Second World War. Greenland acquired a pivotal position in the nuclear arms race as the progress in both nuclear bomb technology and in connected delivery technology (the development of long-range bombers and missiles) in the postwar period greatly increased Greenland’s importance for US defense and military strategy. Already in 1941, the Danish ambassador in Washington, Henrik Kauffmann, signed a defense pact allowing the US extensive military base rights in Greenland in exchange for military protection while mainland Denmark was occupied by Germany. Once there, the American military never left, although military rights and defense prerogatives have changed somewhat over the years and, like today, the American interest in buying Greenland was specifically tabled in 1946-47 when the Danish Government wanted to terminate the 1941 agreement.

However, there is a huge difference in how the US’s approach was handled and perceived in 1946-47 and in 2019. This is due to the fact that there has been both a profound change in the mode of policy-making in the US itself, as well as a change in the perception of colonialism in the world in general and in the status and position of Greenland within the Danish Realm more specifically. Let us see how.

The Truman administration’s Cold War bid for Greenland

The US bid to buy Greenland in 1946 came as a countermove to the Danish wish to terminate the earlier agreement from 1941. The idea was presented to the Danish government when foreign minister Gustav Rasmussen paid a visit to Washington in December. His US equivalent James Byrnes presented three options on that occasion:

- an extended base agreement allowing the US to construct various military base and defense zones in Greenland with full US military control and full freedom of movement within these areas;

- a defense agreement entrusting the US with the task of defending Greenland (essentially an outsourcing model); and, finally,

- the sale of Greenland to the US – the preferable option, as Byrnes made clear.

According to US sources, Gustav Rasmussen was completely taken aback by the third option. As Rasmussen allegedly and quite pointedly told the US ambassador to Denmark one month later: “While we owe much to America, I do not feel that we owe them the whole island of Greenland”. On the surface, this reaction resembled the Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen’s public reaction characterizing Trump’s 2019 bid as “an absurd discussion”.

This 1946 incident is interesting for at least two reasons: The American wish to buy and the Danish refusal to sell. If we consider the American perspective first, it is well known that the purchase of land was by no means a novel option in the political tool box of the US. Expansion both in mainland America and elsewhere, e.g. Alaska and the US Virgin Islands, had often taken place through purchase agreements. However, when seeking to organize a new international order after World War II, the USA sought to position itself as the champion of a new post-colonial world and put pressure on European states to end colonial domination overseas. Severe pressure on the Dutch government to grant independence to Indonesia is a particular case in point.

A picture of Harry Truman (left) and James Byrnes (right) shaking hands from around the same time (1946). Photo: US National Archives. Public domain.

Nevertheless, the US did not shy away from attempting a colonial bargain with the Danish government over Greenland – without involving the native inhabitants of the territory. In the American view, Greenland was positioned within the boundaries of the Monroe Doctrine and, as such, other rules applied, especially when strategic considerations were as salient as in the case of Greenland; in a looming nuclear age, US strategists and decision-makers concluded that Greenland’s strategic value would likely increase and this overruled all other concerns.

“while we owe the US a great deal, I do not think we owe them the whole island of Greenland”

The approach taken by the early postwar governments in Denmark not to sell is even more complex to decipher since in many ways selling Greenland would have been a practical solution – a solution which grew in attractiveness in step with the intensification of the Cold War. By selling, Denmark would have freed itself from the administration of a true Cold War hot spot. There was a widespread fear in the Danish government that the US claim to Greenland would prompt the Soviet Union to increase the pressure on Denmark at a time when it had only just left the Baltic island of Bornholm after nearly a year of occupation. Without Greenland, one might argue, it would have been easier to pursue the traditional Danish security policy option of steering a course that did not rely on bloc alignment.

Furthermore, selling Greenland must have been tempting for purely economic reasons. As actual negotiations were in fact never initiated, we do not know what the price would have been: At the time, rumours in Copenhagen suggested that it would have been one billion dollars – or nearly four times as much as Denmark’s Marshall Aid. Although these rumours may have overstated US generosity, there is no doubt that a sale would have funnelled a substantial sum of US dollars into the Danish treasury at a time when nearly all European countries, including Denmark, were desperate to close the growing ‘dollar gap’ and to satisfy both investors and consumers in the domestic market. Yet, the government did not take the bait. Why so?

In his immediate response to the American bid, Danish foreign minister Gustav Rasmussen in December 1946 countered the US argument that Greenland was no economic asset to Denmark by stating that neither money nor economic considerations in a broader sense determined the relationship with Greenland. What counted, he stressed, was the fact that Greenland was attached to Denmark through tradition and history. He was right in the sense that Greenland hardly contributed to the Danish Treasury in a positive sense. However, in the early post-war years, the Danish government was preparing to allow greater access to trade and resources in Greenland which was a break with the restrictive, monopolizing approach that had been the rule previously. This was done with a view to boosting and opening up the Greenlandic market in resource exploitation (among them fishing), construction and trade (an investment approach, which also required further state transfers to Greenland). Thus, despite the fact that climate change was by no means a theme in the late 1940s, there was widespread expectation that Greenland might have much to offer in the future in terms of resources and raw materials.

Hans Hedtoft in Greenland in 1947 from Viceadmiral A. H. Vedels photo collection. Photo: Danish Arctic Institute.

That said, the tradition and history argument was nevertheless valid in two ways. First, the rhetoric of cherishing the centuries-long relationship between Greenland and Denmark was not merely part of a discourse legitimizing colonial rule. In both broader Danish society and among top administrators and politicians, one can detect a real sense of commitment and concern for Greenland and its population, albeit in a paternalistic sense resembling Kipling’s remarks concerning the ‘white man’s burden’. Thus, sentimental and emotional bonds actually did exist – probably also reciprocated by sections of Greenlandic society, although Greenlandic national self-awareness was on the rise. The paternalistic approach was prominent in the government’s understanding of the issue, but it is also obvious that the new Social Democrat government under Hans Hedtoft (who took office in late 1947) wanted to place the Danish-Greenlandic relationship on a more contemporary footing. According to Hedtoft, discussions concerning the new organization of Greenland’s status and the modernization of its economy, which the government was intent on seeing through, “would build a base for a lasting relationship between Denmark and Greenland which will be much stronger than sentimental figures of speech about common national feelings.”

Second, and in combination with the paternalistic rhetoric, the possession of Greenland had another historical quality, namely, lending a certain element of grandeur to a state that had otherwise only known loss of territory in recent centuries. In this sense, Greenland could be likened to the ‘brightest jewel’ in Denmark’s crown as India had been in its relation to Great Britain. Interestingly, the time of India’s independence in 1947 was exactly the time when the USA informally floated the idea of buying Greenland from Denmark.

The 1951 agreement on the defense of Greenland

Denmark kept its empire and refused to let go, even with the promise of a massive influx of much-needed dollars. Nevertheless, the Danish success was obviously more apparent than real, because the refusal to sell Greenland had not resolved the basic issue that successive Danish governments wanted to terminate the 1941 agreement in order to reduce the US presence in Greenland. All the same, in the light of US purchase pressure, they now shied away from pushing the issue. Firstly, because they did not want the issue to be politicized and internationalized as this might present the Soviet Union with a pretext for engaging in counter-pressure; and, secondly, because it became increasingly clear to decision-makers that Danish Cold War security in the last instance relied on US defense commitment and capability. ”Don’t bite the hand that feeds you” seems to have been the strategy in place. For a brief period, the Hedtoft government believed that Danish membership of the Atlantic Pact might produce a satisfactory solution. Its appeal lay in that a multilateralization of the defense of Greenland within NATO would reduce the US presence and prevent Denmark from confronting the US on its own in bilateral discussions.

All the same, this hope quickly proved to be in vain, since this was not what the US government had in mind. The US wanted to retain a maximum of national control over the issue of Greenland and consequently to only negotiate a bilateral solution. In the end, they had it their way. This materialized when Denmark and the United States agreed a new treaty concerning the defense of Greenland in 1951, replacing the previous agreement from 1941. The far-reaching character of US military rights in the rather vast defense areas designated by the treaty and the only token respect for Danish sovereignty are both manifestly expressed in article II, section 3(b):

“Without prejudice to the sovereignty of the Kingdom of Denmark over such defense area and the natural right of the competent Danish authorities to free movement everywhere in Greenland, the Government of the United States of America, without compensation to the Government of the Kingdom of Denmark, shall be entitled within such defense area and the air spaces and waters adjacent thereto: ... to construct, install, maintain and operate facilities and equipment ... and to store supplies.”

On the basis of such liberties it is no wonder that a Pentagon official, in a report to President Eisenhower in the late 1950s, noted that the Danish government had been “very cooperative in allowing the United States quite a free hand in Greenland.” In Greenland, there was obviously some distance between fact and fiction when it came to determining sovereignty.

Sovereignty and decolonization: The reformulation of the status of Greenland

In a case called by Norway in 1933, the International Court of Justice ruled that full sovereignty over Greenland resided with Denmark. This does not tell the full story of who has held de facto sovereignty in Greenland, however. Danish-US negotiations on allowing the US access to and base rights in Greenland was a bilateral Danish-US affair that did not involve the Greenlandic population. When foreign minister Ramussen declined the US offer by stating that, “while we owe the US a great deal, I do not think we owe them the whole island of Greenland”, the “we” referred to Denmark and the Danish government. It did not include the Greenlandic population. It was a colonial deal where nobody disputed the US right to buy and the Danish right to sell without involving the Greenlandic people. This is the huge difference between the situation in the early postwar period and today.

Over the years, Danish governments have constantly engaged in reformulations and re-negotiations of sovereign rule in relation to Greenland and the Greenlandic people. The main reason behind these reformulations has been that two grand historical trends or structural changes within global history intersected and converged on Greenland, namely, the Cold War clash between East and West, and the fraught and changing nature of the relationship between North and South, expressed in the global trend towards decolonization. Both of these dynamics severely challenged Danish sovereignty in Greenland.

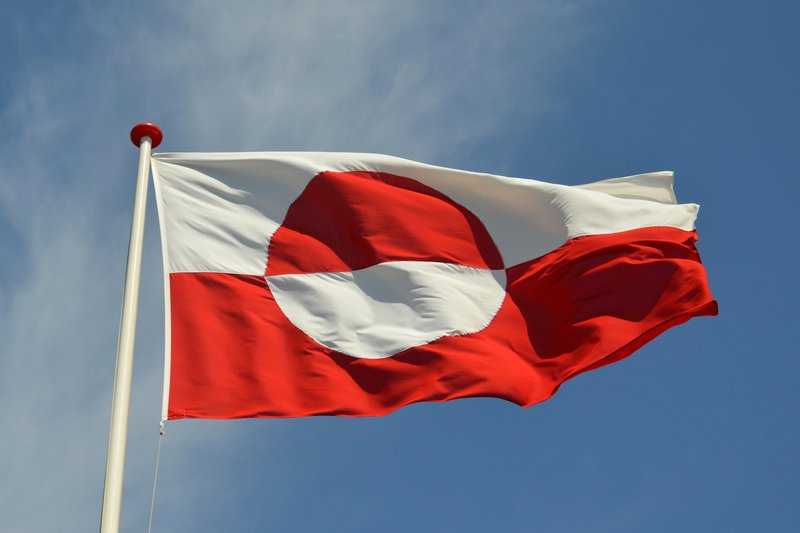

The Greenlandic flag flew for the first time on 21st June 1985 on Greenland's national day. The flag is drawn by the painter Thue Christiansen and represents the rising sun over the polar ice. The colours are the same as the Danish national flag, the Dannebrog, to represent the connection with Denmark and Norden. Photo: Colourbox.

There is hardly any doubt that Danish governments felt that they were able to manage the challenge brought about by decolonization in a more satisfactory manner than the challenge stemming from the Cold War. They also believed that they were ultimately successful in keeping the two challenges separate, e.g. by making the US accept a ‘fraternization ban’ on contacts between US military personnel and Greenlanders. In terms of power, there was a clear asymmetry involved in both challenges. In the Danish-Greenlandic relationship, it was the Danish government who held the right of initiative, set the rules and fundamentally dictated a modernization strategy, which aimed at accomplishing (and controlling) Greenlandic self-determination through closer integration into the Danish Realm. In the Danish-American relationship it was very much the other way around.

Concerning the Danish-Greenlandic relationship, it could be argued that the modernization of the country during the 1950s in fact became the road to increased Greenlandic self-determination. In 1979, a so-called home rule agreement came into force and in 2009 self rule was introduced, meaning that Denmark today recognizes Greenland as a rightfully independent nation. For the moment, responsibility for foreign policy, security policy and certain financial policy areas still reside with the Danish government. But, these important policy areas, including full control over raw materials policy and administration, may be transferred to Nuuk – and in fact control of raw materials has already been transferred. The judicial essence of the 2009 self rule status is that Denmark recognizes that Greenland has the right to become independent if the population so wishes and this is the point that the Trump Administration – and even some Danish commentators and politicians – have basically not understood.

Trump’s 2019 bid for Greenland

Today, Trump is behaving like the Truman administration in 1946, only less sophisticated, and – even worse perhaps – it does not seem to understand that the world, including Greenland’s status within the Danish Realm, has changed since then. Denmark cannot sell Greenland in a bilateral colonial deal with the US anymore. Greenland has acquired self rule and has the right to be consulted on all major aspects of relevance. It holds the right to veto any move made by ultimately claiming independence. This is why Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen hit the nail on the head when she – during a visit to Greenland – characterized the US advance as an “absurd discussion”, adding that, “Greenland is not for sale. Greenland is not Danish. Greenland belongs to Greenland.”

However, what is important to note is that Greenland’s strategic position and the US interest in the island will continue to weigh on the Danish-US relationship, but also on that of Denmark and Greenland. In this sense, the situation today has not changed that much since the early postwar. After Trump called Frederiksen’s comment “nasty” and cancelled his planned visit to Denmark at the beginning of September 2019, the Danish government has worked overtime to convince the US government about its backing as an ally to the US and supporter of US Arctic policies. With some success it seems as President Trump subsequently publicly declared Frederiksen to be a “wonderful woman.” The Danish-US relationship is still the asymmetrical one of the the dwarf to the giant.

However, what is important to note is that Greenland’s strategic position and the US interest in the island will continue to weigh on the Danish-US relationship, but also on that of Denmark and Greenland. In this sense, the situation today has not changed that much since the early postwar. After Trump called Frederiksen’s comment “nasty” and cancelled his planned visit to Denmark at the beginning of September 2019, the Danish government has worked overtime to convince the US government about its backing as an ally to the US and supporter of US Arctic policies. With some success it seems as President Trump subsequently publicly declared Frederiksen to be a “wonderful woman.” The Danish-US relationship is still the asymmetrical one of the the dwarf to the giant.

The stepped-up US interest in Greenland will also come to weigh on the Danish-Greenlandic relationship in the future. In September 2019, the US has announced that it wants to reopen a consulate in Nuuk, which will allow the US a stronger presence in Greenland and increase the prospects of influencing Greenlandic decision-makers and the public. There is a strong sentiment in some parts of Greenlandic society to opt for full independence from Denmark, although it will be difficult for Greenland to live without the administrative resources and cash transfers it receives from Denmark. The latter amounts to nearly one third of Greenlandic GDP. If Greenland was interested in affiliating itself for a better deal with the US, it could do so – a scenario which may be shown to function as a bargaining chip in its dealings with Denmark in the future. However, Greenland may also want to become fully independent without incorporation into another state. As history suggests, being the ‘Pearl of the Mediterranean’ will come at a price even despite formal independence. During the Cold War, Denmark could only uphold a fictitious sovereignty over Greenland as defense of the island was in practice out-sourced to the US. The same situation will impact, maybe even to a higher degree, on an independent Greenland. It will not be easy for 56,000 inhabitants to uphold national sovereignty over the world’s largest island. Therefore, the present scramble for the Arctic could easily prove to be a blessing in disguise for Greenland.

Further reading:

- Paul Claesson, Grønland- Middelhavets perle [Greenland: The Pearl of the Mediterranean] (Copenhagen; Vandkunsten, 1983).

- Thorsten Borring Olesen, 'Tango for Thule. The Dilemmas and Limits to “the Neither Confirm nor Deny Doctrine” in the Danish-American Relationship, 1957-1968', in Journal of Cold War Studies, 12, 3 (2011), pp. 116-147.

- Thorsten Borring Olesen, 'Between Facts and Fiction: Greenland and the Question of Sovereignty 1945-1954', in New Global Studies 7,2 (2013), pp. 117-128.

Links:

- Article on Politico, 'Sure, Trump can buy Greenland. But why does he think it’s up to Denmark?'

- The Danish Arctic Institute

- worldcourts.com for relevant rulings at the Permanent Court for International Justice from 1933.

- The history of Greenland (in Danish) on danmarkshistorien.dk.

- American TV programme on the building of the Thule airbase in 1950s, Operation Blue Jay on YouTube.