Scandinavian Apologies and Compensation to Indigenous Peoples

Human rights violations require meaningful responses, but whether "sorry" is significant depends on the context

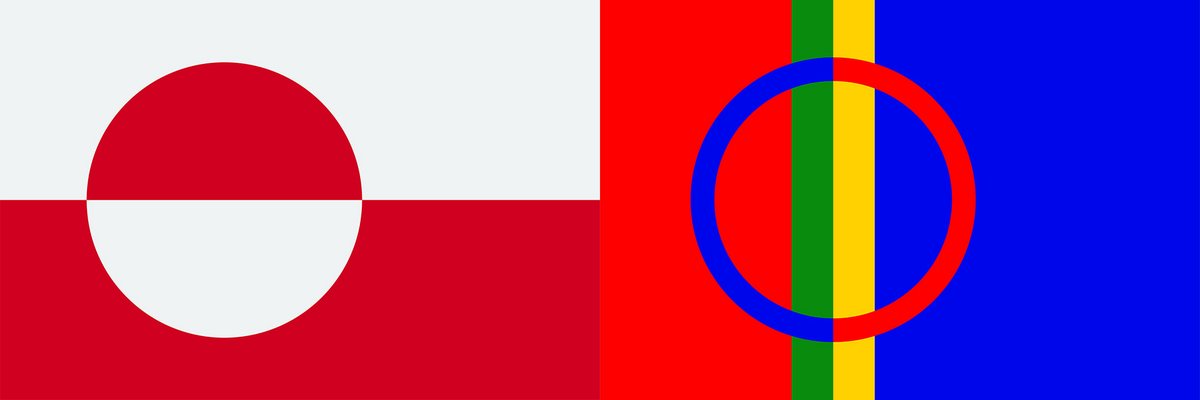

Summary: Official apologies for human rights violations perpetrated by colonising countries often attract much media attention. However, the actual meaning of an official apology and the concrete consequences emanating from it are usually highly ambiguous, particularly as indigenous communities may well be advocating for some other type of remedy. Examples from each Scandinavian country suggest that the path from apology to compensation is rarely straightforward, and the popular fixation on the official apology can even obfuscate important steps towards justice for indigenous communities, such as the Inuit and the Sámi.

In an episode of the Danish drama series Borgen broadcast in 2010, a fictitious Danish prime minister receives the following piece of advice from her permanent secretary:

"Sorry’ is a word that we are historically on the fence about when it comes to Greenland. It places responsibility and often leads to unexpected expenses."

Although it comes from a fictional series, this example shows a general tendency to mix up the legal human rights terms “apology” and “compensation” and to assume what an indigenous community demands rather than listen to its actual requests. The attention of journalists and politicians repeatedly seems fixated on official apologies and whether to give them or not, but in a legal sense, apologies are highly ambiguous and the indigenous communities typically at the centre of apology-debates often advocate for other types of remedies for human rights violations.

This highlights the importance of distinguishing between what certain groups demand and what politicians and other public figures provide in response. On the one hand, the words “apology” and “compensation” appear linked since apologies can spur legal compensation cases, but on the other hand, politicians might view an apology as a way of bringing calls for compensation to an end. So, what is the difference between these various approaches? And how have the Scandinavian countries and indigenous peoples connected to these navigated between these two takes on addressing human rights violations in recent history?

Indigenous Peoples and Scandinavia

All three Scandinavian countries have connections to indigenous peoples. The Sápmi territory of the Sámi spans across Norway and Sweden, amongst other countries, and with Kalaallit Nunaat being part of the Unity of the Danish Realm, the Inuit still share a connection with Denmark. The United Nations has declared the Sámi and Inuit as indigenous peoples, which grants them certain internationally valid rights, in addition to the general rights stated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights from 1948. The 2006 Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples specifies the human and legal rights of peoples such as the Sámi and Inuit and provides international standards for how these should be upheld and reclaimed if breached.

A word on language: Kalaallisut is the only official indigenous language in Greenland, although there are several indigenous languages spoken, in addition to Danish. There is a difference between referring to a country by a name given by the coloniser (Greenland is a direct translation of the Danish “Grønland”) and the name used by the indigenous population, “Kalaallit Nunaat” (the Kalaallisut term when referring to Greenland). I have chosen to use the latter and also the Sámi term "Sápmi" for the territory inhabited by them, instead of Lapland.

An official apology is not always connected to compensation

Although it frequently draws headlines in discussions connected to slavery and colonialism, an official apology is actually a subcategory of the human rights legal term “satisfaction.” Historical research into human rights breaches and their public commemoration has shown that an official apology is most effective in combination with other types of satisfaction. It is therefore rarely the goal in itself. Additionally, it is difficult to produce an international definition of an official apology, as national variations of the word “apology” skew its meaning. However, when an official figure, usually the head of state or monarch, gives an apology it can be interpreted as leverage in compensation cases, although the apology does not necessitate compensation. Thus, a legal procedure cannot be carried out in order to get an apology, but the apology may generate awareness and can be included as evidence in court.

The Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples does not mention any right to an official apology, likely because of the lack of a universal definition as mentioned above, but indigenous peoples’ right to compensation is fleshed out in the declaration. In contrast to the legally ambiguous apology, compensation cases can be carried out in the courts. The declaration very straightforwardly defines compensation as:

Compensation is the return of “lands, territories and resources equal in quality, size and legal status [to what has previously been taken from the indigenous population] or of monetary compensation.”

The amount of money or territory to be given to the indigenous group seeking compensation is of course still up for debate, but this definition gives indigenous peoples a legal claim to bring compensation cases against former colonisers and other countries or institutions they believe have wronged them. Monetary compensation can be either individual (a sum given to each of the people wronged) or collective (a larger sum meant to benefit the community as a whole).

Scandinavian Examples of Apologies and Compensation

The following sections provide an example from each Scandinavian country of the intersection between apologies and compensation. The overview shows that the path is not always from apology to compensation, that the indigenous peoples seeking compensation do not always receive what they wish, and that apologies are not always the grand gestures that media outlets present them to be.

Denmark

In 1953, the Danish government forced a hasty relocation of the Inuit population of the Thule area in Kalaallit Nunaat in order to make room for a US air base. The relocated Thule population attempted a compensation case twice, but partial compensation was not granted until a Danish high court case that took place from 1996 to 1999. During this case, the group put forward a claim on territorial, individual and collective compensation, but only achieved minor collective compensation. The end of the court case prompted an official apology from the Danish Prime Minister, which was phrased as an appeal to focus on future collaboration within the Unity of the Danish Realm. This example quite clearly illustrates how apologies are occasionally neither the original goal nor an acceptable outcome to indigenous people because the population of Thule appealed the high court’s decision to the supreme court, which denied the appeal in 2003. The Thule population further appealed the decision to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), claiming that the forced relocation was a breach on the International Labour Organization’s Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (this case was carried out before the 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples). This claim was denied by the ECHR in 2006. So, although the Prime Minister’s apology was included in the case files made available to the ECHR, it was not sufficient legal leverage to change the decision made by the court.

Norway

According to the Political Apologies Database, the Norwegian King’s (Harald V) apology in 1997 for injustices committed against the Sámi was the first official apology given by a public figure of authority in any of the Scandinavian countries. The apology referred to the “norwegianisation” (fornorsking) of the Sámi in the 19th-20th century during which Sámi culture and language was systematically suppressed as an official, political decision. In his New Year’s speech on 1st January 2000, the Norwegian Prime Minister announced the government’s intention to establish a fund for the Sámi population of Norway as collective compensation for the damages caused to their community by the norwegianisation policy. The fund proposal won a majority vote in the Norwegian parliament in June 2000 and was designed to support community-enhancing projects and would be managed by Sametinget, the Sámi parliament of Norway. This example shows the perhaps often politically feared route from apology to compensation, but then again not entirely, seeing as the compensation was in this case not the result of a legal battle but rather an attempt to follow up on the apology with actual political action.

A word about translation: In English, an "apology" is usually more official that saying "I am sorry". An apology can be given by a person who has not perpetrated the action for which they are apologising for, and it can constitute a human rights satisfaction. Giving an official apology in Danish and Norwegian can be semantically tricky, as the word “apology” in both contains the term “skyld,” which means guilt (unnskyldning and undskyldning, respectively). So, an official apology given by an authority seeking not to assume responsibility might indicate otherwise. Swedish does not have this challenge with "ursäkt" (apology) and "förlåt" (sorry) being more akin to the meaning of the English words.

Sweden

The Swedish state has not given the Sámi community of Sweden an official apology, but the Church of Sweden has apologized twice – in 2021 on Swedish territory and in 2022 in Sápmi. It is noteworthy that the first apology was not accepted by the Sámi community, and they only accepted the 2022 apology when it was supplemented by an action plan for how to further amend wrongs of the past done by the Church of Sweden to the Sámi community. From a legal point of view, the action plan appears far more intriguing than the apology itself. It declares the Church’s official support of the Sámi's rights to forestry and land management, thus acknowledging their indigenous right over historical territories, a right also emphasized in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. This right was certainly not a given at the time, as a Sámi community had only two years previously brought a case against the Swedish state in order to establish hunting and fishing rights within its territory. In this example, declarations of support for an indigenous group’s right to its territory may have a bigger legal and political impact than an apology, and apologies are not always initially accepted as solutions to disputes.

Apology only one element of a broader process

In short, instead of focusing on official apologies as solutions to improving relationships between indigenous peoples and the Scandinavian countries, it makes more sense to view an apology as one element of a broader process of remedying human rights violations.

Apologies may generate attention and even occasionally lead to compensation, but other gestures or political decisions are more likely to aid these tense relations than an apology.

Analysing colonial relationships sheds light on contemporary public debates

This article was published in response to readers' interest in indigenous rights, equality and minority groups.

Further reading:

-

Anne Kirstine Hermann, Imperiets Børn. Da Danmark Vildledte FN for at Beholde sin Sidste Koloni [Children of the Empire. When Denmark misled the UN to keep its last colony] (Lindhardt & Ringhof, 2021).

-

Peter H. Rehm and Denise R. Beatty, 'Legal Consequences of Apologizing', Journal of Dispute Resolution (1996), pp. 115-130.

Links:

- Research project, TRiNC: Truth and Reconciliation in the Nordic Countries, funded by the Danish Research Council.

- Research project, Political Apologies Across Cultures, funded by the European Research Council.

- Uses of the Past (research center)