The Borders of the Nordics

The Borders of the Nordics

The internal and external borders of the Nordics have changed throughout time, just like many other countries and regions. In the article the History of Iceland, you can read about Iceland coming under the Danish-Norwegian Crown in 1380, a Danish dependency from 1660, and finally gaining independence in 1944. The Kalmar Union existed between Denmark, Norway and Sweden in various forms from 1397 to 1521. In 1521, Sweden left the union leaving Denmark-Norway, which existed until 1814 when Norway become an independent nation. Sweden-Finland existed from 1100s to 1809 when Finland became a part of Russia until 1917.

Today, the Nordics are considered to be five nation states. However, this rather conceals a number of significant arrangements. For example, the Faroe Islands and Greenland both have home rule, although they are ostensibly part of the Danish realm and each have two members of parliament in Copenhagen. The Åland Islands lie at the south-western tip of the Finnish peninsula between Finland and Sweden and are made up of an archipelago of 6,500 islands and skerries. This too is an autonomous region and a Swedish-speaking part of Finland.

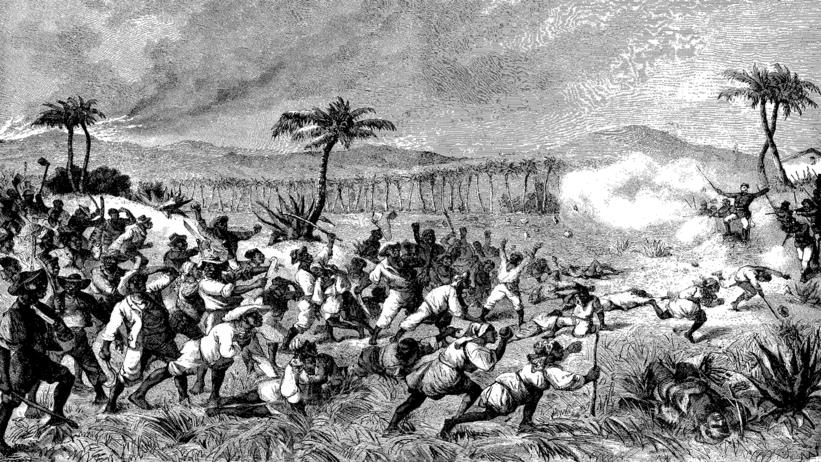

The image of the five nation states in Northern Europe also overlooks colonial relations. Greenland went from being seen as a colony to a Danish county in 1953 as part of the Danish decolonisation of Greenland, 1945-54 and its status is still debated and somewhat controversial, not least when President Donald Trump raised the idea of ‘buying’ Greenland in 2019. And the Danish West indies, crucial for the Danish economy throughout much of the 18th and 19th centuries due to primarily sugar plantations, were sold to the Americans in 1916. Slavery was abolished on the islands in 1848, but even after this time, conditions for workers in the plantations were not much improved.

PICTURE: A drawing from the Danish magazine Illustreret Tidende reporting on the fireburn uprising in November 1878 on the Danish West Indies. The National Museum of Denmark. Public Domain.

So, what have borders meant in the Nordics and how has their geographical position in the north affected them?

Between east and west

During the Cold War, the Nordics were often seen as being neutral and geographically and politically sandwiched between the Eastern and Western bloc. A tendency towards non-alignment during conflicts has existed in all the Nordic countries, detailed in the article Neutrality and the Nordic countries. Norden became known as a geopolitical bloc, ‘Cold War Norden’, with particularly low tension and a self-neutralising status built around a self-enforcing aggregate perspective on the different countries security policy. This also enabled them to take a bridge-building approach to East/West relations during the Cold War era. For example, the term ’bridge-building’ is often used to describe Norwegian foreign policy from the tail end of the Second World War until Norway's turn to the West in early 1948, which is explained in the article Norway, the West and the Soviet Union, 1944-48.

The territory on the border between Finland and Russia has been significant for the relations between the two countries, particularly Karelia. Also, Ingria connects modern-day Finland with modern-day Estonia, between the Baltic Sea and Lake Lagoda. Dominated by the city of St Petersburg today, Ingria has seen numerous invasions, annexations and changes to state boundaries over the last 400 years. Ingrian Finns came to the region in the seventeenth century. The region is characterised as a region of political and ideological borders – at various times, constructed as the dividing line between Finland and Russia, capitalism and communism, East and West.

Greenland was also a political hot potato during the Cold War situated as it is between the US and Russia. Greenland acquired a pivotal position in the nuclear arms race as the progress in both nuclear bomb technology in the postwar period greatly increased Greenland’s importance for US defence and military strategy.

Once there, the American military never left, although military rights and defence prerogatives have changed somewhat over the years, as detailed in Buying Greenland? Trump, Truman and the 'Pearl of the Mediterranean'.

PICTURE: The border between Sweden and Norway. Photo: Karin Beate Nøsterud, norden.org. CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0

To the north of the North

Greenland and the other Nordic countries are strategically placed near the Arctic, and all are members of the Arctic Council. The Council was established in 1996 by the Ottawa Declaration with the intent of fostering “cooperation, coordination, and interaction between the Arctic states.” Everyone has some image of what the Arctic is like: it conjures up images of an extreme environment, white and cold, or giant ice floes melting away as the impacts of climate change are felt. We should be wary of simplistic images, however, as set out in the Quick Read on the Arctic Imaginary.

The Sámi peoples live in Sápmi in northern Norway, Sweden, Finland and parts of Russia. There are different branches of the Sámi language, which is a member of the Finno-Ugric language group and thus related to Finnish. Amongst other things, Sámi culture includes Sámi handicraft, Sámi yoiking (a musical expression), and Sámi literature.

You can watch a short interview with Associate Professor at The Arctic University of Norway, Lill Tove Frederikson to hear about her discovery of Sámi songs and the differences between the generations, her mother’s and her grandparents having experienced Norwegianisation.

PICTURE: The Sámi people have traditionally lived in the Northern part of Norden, but across the national borders of Norway, Sweden and Finland. The photo shows Sámi people from Finmark, Norway in 1951. Photo: Nasjonalbiblioteket (nb.no). Public Domain.

To the south

Denmark is the Nordics most southern country. The bridge across the Oresund to Sweden is a globally renowned icon. Completed in 2000, it is a symbol of many things, including Nordic cooperation in the economy and engineering and the solving of grisly real or imagined crimes, due to the popularity of the Danish/Swedish TV show The Bridge. The short history of the Oresund Bridge sets out that it is an undeniable, physical link between continental Europe and the rest of the Nordics, and an image of cross-border relationships.

The borderlands between Denmark and Germany offer rich cultural and political histories with a Danish minority on the German side, and a German Minority in Southern on the Danish side. This is largely due to the history between the countries, not least the loss of a third of Denmark’s territory in 1864 to the Prussians. After the loss of Norway in 1814, Denmark’s territory was severely reduced and is said to have led to a collective trauma for the country, as set out in the meaning of the Second Schleswig War ('1864') in Denmark.

In 1920, in the aftermath of the First World War, the Danish border moved south again after a plebiscite where the population of two zones were allowed to vote on whether they wanted to be Danish or German. The circumstances are recounted in the article the reunification of Denmark in 1920.

Minorities and the movement of people across borders

The porosity or otherwise of both the internal and external borders has naturally led to different trends in the population, which you can read about in An overview of population trends in the Nordic countries since World War II. An overview of minorities in the Nordic countries sets out that they include the indigenous Sámi population; national minorities, such as Germans in Southern Denmark; immigrants from other Nordic and neighbouring countries as well as further afield; and other groups, such as Greenlanders in Denmark.

The question of language amongst minorities is often debated in the context of schools and the situation of immigrant women. Policy oscillates between assimilationist tendencies – everyone should receive the same language training, and multiculturalism – everyone has the right to receiving instruction in their mother tongue. You can read more about this topic in Minority languages in the Nordic countries and Multiculturalism.

Finland has two official languages, Finnish and Swedish, as a result of its more than 600 years as part of the Kingdom of Sweden (until 1809), as set out in Swedish speakers in Finland. While the Swedish-speaking minority has remained relatively small, the Finnish Constitution and other relevant legislation guarantee them the same language rights as Finnish speakers. This has resulted in bilingual public and private services and organisations, and the relationship between the two language groups has led to both friction and been a source of artistic inspiration.

Freedom of movement between the Nordic countries started already in 1954 and continues to this day. Each of the Nordic countries has a different relationship with the EU and therefore association to free movement of goods, services and workers within the EU. You can read more about this on the theme page Nordic Labour Markets.

Movement of people across the borders of the Nordics has included emigration, which is briefly set out in Emigration in the Nordics: an overview since 1800s.

Movement of people across the borders of the Nordics has included emigration, which is briefly set out in Emigration in the Nordics: an overview since 1800s.

PICTURE: The photo above is a snapshot of everyday life in Nørrebro, one of the most multicultural parts of Copenhagen. Yadid Levy, norden.org. CC-BY-NC-SA-4.0

Immigration policy remains a polemic area. Danish immigration policy, 1970-1992 spans a period of time when the country first needed more workers so encouraged labour immigration, to a later period when policy-makers introduced restrictions. Different angles on the issue can also be read in a brief history of Islam in Denmark, Political approaches to immigration in Scandinavia since 1995, and the articles on racism and anti-racism in the Nordic countries.

Further reading

- Giang Ho and Kazuko Shirono, The Nordic Labor Market and Migration, International Monetary Fund Publications (International Monetary Fund, 2015).

- Gunnar Karlsson, Iceland´s 1100 Years. The History of a Marginal Society (United Kingdom: Hurst & Co, 2000).

- H. Lödén, ‘Reaching a Vanishing Point? Reflections on the Future of Neutrality Norms in Sweden and Finland ’, in Cooperation and Conflict 47, 2 (2012) pp.271–284.

- Synnøve Bendixsen, Mary Bente Bringslid and Halvard Vike, eds., Egalitarianism in Scandinavia: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives (London: Palgrave, 2018).

- Ebbe Volquardsen and Lill-Ann Körber, The Postcolonial North Atlantic: Iceland, Greenland and the Faroe Islands (Berlin: Nordeuropa Institut der Humboldt Universität, 2014).

- Olav Riste, Norway’s Foreign Relations – A History. (Oslo, 2005).

- Tom Nauerby, No Nation is an Island: Language, Culture, and National Identity in the Faroe Islands (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 1996).