The Events of 1814: A Scandinavian and European Story

The end of a 434-year political union between the kingdoms of Norway and Denmark.

Summary: 1814 saw an end to a 434-year political union between the kingdoms of Norway and Denmark (1380-1814). No Norwegians were present when this was negotiated in Kiel, and Norway seized its chance, briefly adopting a liberal constitution from May of that year, with the support of the Danish heir to the throne who was in Norway as viceroy at the time. Prince Christian Frederick was declared king but was forced to abdicate later that year to make way for a Swedish-Norwegian personal union. This loose union would last until 1905, significantly changing the balance of power in the Nordic Region. Despite the split in 1814, Denmark and Norway continued to have close cultural and linguistic ties well into the following century.

The year of 1814

Although the story of 1814 is usually told from a Danish, Norwegian or Swedish point of view, what led to it and what followed is a common Scandinavian story. In Danish and Swedish historiography, Norway is often omitted. Norwegian history from 1380 via 1814 to 1905 cannot be written quite so easily without including Denmark and Sweden, and while Norwegian history speaks of "the Danish era", there is – at least not yet – a similar "Norwegian age" in Danish history.

The outcome of the Treaty of Kiel, in which Frederick VI (born 1768, king 1808-1839) reluctantly had to pass Norway over to the Swedish king, was lamented by many in Denmark and later referred to as "the loss of Norway". In Norway, on the other hand, many seized the opportunity for greater independence with fervour, and the dissolution of what was also known as the "Twin Kingdom" (Tvilling-Riget) was in general not seen as a loss, although there were those who did mourn the break-up.

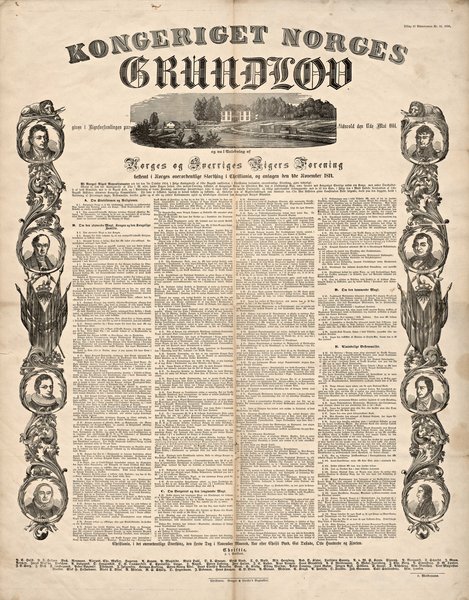

For Norwegians, 1814 was a new beginning, a leap from being an integral part of one of Europe's most restrictive absolutist states to becoming (more-or-less) an independent nation, or at least an autonomous state, with one of the most liberal constitutions, the Eidsvoll Constitution of 17th May 1814. The autumn of 1814, despite Norwegian opposition, ended with a looser form of personal union with Sweden, in which the Norwegian constitution, in a somewhat revised form, was recognised and gave the Norwegian Parliament power to tenaciously resist later Swedish attempts to bind the countries closer together.

"The lost Norway" or "The lost 400 years"?

The Norwegians called the long period that they had been part of the Danish composite state as the “the lost 400 years” (svundne 400 år), or later the “400-year night” (400-årsnatten), and they criticised Denmark for limiting Norway's development due to these lost centuries. At the same time, Norwegian historiography placed increasing emphasis on the country's tradition as an independent kingdom before the union, the Old Norwegian days of glory in the 1200s, when Norway was a large North Atlantic kingdom with its own church, laws, language, and culture.

For Norway, the events of 1814 brought an end to a long existence under Danish domination. From 1380 to 1814, Norway and Denmark were linked in a common polity that varied in strength and proximity, and with Sweden also being part of the Kalmar Union for certain periods (1397-1523). It was not a given that this state construction would last so long, or that Norway, which formally remained a separate kingdom throughout the period, would become a subordinate party to the extent that it did. However, even in the development from a Scandinavian three-state union to a Danish-Norwegian dual monarchy, there was an underlying and continuous strengthening of Danish royal power and centralising of state government. Political power was increasingly concentrated in Copenhagen, and Norway gradually became, to all intents and purposes, a Danish province – a province that however gained in importance towards the end of the union era.

The Swedish plan for a Swedish-Norwegian union

Few in Norway had considered the possibility of putting an end to the long-standing union, although there was growing dissatisfaction with it. The Danish-Norwegian separation was instead forced upon the two countries from the outside. The events of 1814 were the result of Swedish plans and international high politics. The plan was conceived and executed by the Swedish Crown Prince Charles John (born 1763) − the former French Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte − who had now turned against Napoleon. Bernadotte had surprisingly been chosen as Swedish heir to the throne in 1810, the year after Sweden had lost Finland to Russia, and Gustav IV Adolf (1778-1837, king 1792-1809) had been overthrown. He went on to become king of Sweden and Norway from 1818-1844 as Charles XIV John.

In 1812, Charles John had allied himself with the Russian Tsar Alexander I (born 1777, Tsar 1801-1825). Instead of a potential reunion with Finland, which had been part of the Swedish Realm for 600 years, Charles John shifted his geopolitical attention to Norway and the Scandinavian peninsula, relying on older Swedish traditions that stretched all the way back to the 1500s. Thus, Charles John demanded support from the great powers of the time for a union of the Scandinavian peninsula as compensation for the loss of Finland, as well as recompense for Sweden’s promise to support the allies fighting against Napoleon.

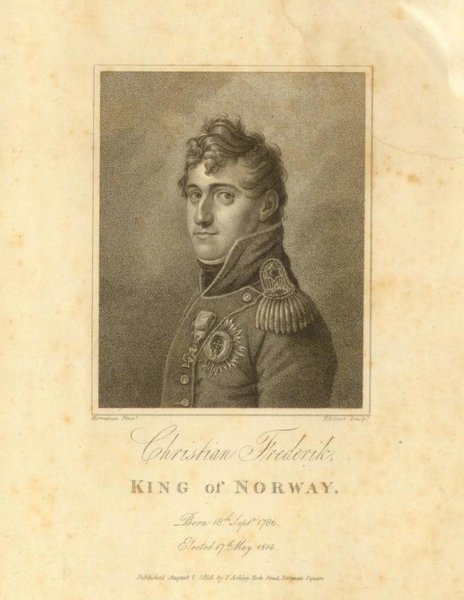

The new policy was set out in international treaties. After the first with Russia in 1812, the important Treaty of Stockholm of 3rd March in 1813 followed, which secured Britain’s acceptance and support for Sweden's claim to Norway. This was also followed by treaties with Prussia and Austria. However, in order to achieve his goal of a Swedish-Norwegian union, Charles John had to force Denmark to cede Norway. The plan was therefore to forcibly take Norway by attacking Denmark. In Denmark, the Swedish plan was well known. While the Swedish Crown Prince was heading south to Leipzig in the spring of 1813 for what became a decisive blow to the French emperor Napoleon I in October 1813, the Danish heir to the throne Christian Frederick (1786-1848, King of Norway 17th May - 10th October, 1814) went in the opposite direction - towards Norway.

A War of Words

In the spring of 1813, King Frederik VI of Denmark-Norway appointed his cousin Prince Christian Frederick viceroy of Norway. On the Danish side, the appointment was part of the effort to maintain the loyalty of the Norwegians, which was no longer something that could be taken for granted. The prince had been kept up to date on developments in the country, including the many Swedish attempts to influence the Norwegians through pamphlets and proclamations. Denmark responded by also producing pamphlets in a veritable propaganda war that peaked in 1813-14, in Norway, Denmark and Sweden, as well as outside the region with the spread of information – and disinformation.

Hundreds of pamphlets, proclamations, speeches and poems, as well as articles in newspapers and magazines, entered into this war of words about Norway. The Swedish aim was to get the Norwegian people to look favourably on a Swedish-Norwegian union and, in a best-case scenario, take the initiative themselves to cast off the Danish yoke. Even though pro-Swedish groups in Norway wanted to leave the union with Denmark, it was difficult to find broad support for a union with their neighbouring country to the east, which for centuries had been Denmark-Norway's archenemy. Several publications were also aimed at an international audience, not least in Britain, whose support was crucial to Charles John being able to carry out his plans.

Treaty of Kiel, 14th January 1814

In late 1813, the Swedish Crown Prince had travelled north from Leipzig with Russian and Swedish troops and had invaded Holstein and Schleswig. During negotiations with the British and Swedish in the Holstein city of Kiel, Frederick VI of Denmark was forced to join the coalition against Napoleon. The Treaty of Kiel between Denmark and Sweden on 14th January 1814 decreed that Norway should be transferred from the Danish to the Swedish monarch – not as a province, but as a kingdom united with Sweden. However, Greenland, Iceland, and the Faroe Islands, which had been Norwegian dependencies, remained in Danish hands. Historians have since debated the reason for these exceptions. It is likely that the North Atlantic islands were not perceived as important by Charles John. Hence, in his geopolitical rhetoric to garner support from the European powers, he consciously focused on a strategically safer Scandinavian peninsula.

Christiane Koren, the Danish-born magistrate's wife who lived not far from Eidsvoll, commented on the dramatic events of the year in her diary. In August 1814 she bitterly stated: "How rich I once was! I had two homelands. Now I have nothing on earth". In the November, she realised that the new union "could well be to the true benefit of Norway" as of the conditions at the time. She noted that the Norwegians had reason to be "at least not displeased".

The Norwegian aspiration for independence

With the Treaty of Kiel, Charles John had seemingly achieved his goal of taking Norway from Denmark – even without any hostilities on Norwegian soil. But the battle for Norway and for the loyalty of the Norwegians was not over. It had only just begun.

The Norwegians did not like to be passed from hand to hand like "a herd of cattle", as it was soon phrased. The Treaty of Kiel marked the beginning of the next phase of the Danish Prince Christian Frederick's Norwegian mission – to lead a Norwegian uprising with the aim of preserving the kingdom for himself and his family, possibly also leaving the door open for a reunification with Denmark. The Swedes could use the threat of war to force the Danes in a certain direction, but when it came to making Norway subordinate, they had limited options.

Furthermore, Charles John could not take his Swedish troops north and secure his victory. The war on the continent was not yet over. In March, the allies reached Paris. It was not until April that Napoleon was deposed and exiled on the island of Elba, and only then could Charles John withdraw his troops. This opened up a window of opportunity in Norway that was greatly exploited by the Norwegians and the Danish prince in the country.

It was not until almost a month after its signature that Christian Frederick received a copy of the full peace treaty from his cousin Frederick VI, the King of Denmark. Having also received the Danish king's open letter and the proclamation formally releasing the Norwegians from their oath of allegiance to the monarch, it was important to act quickly. The kingdoms were now separated, as prescribed in the Treaty of Kiel, and Frederick VI surrendered his power over Norway. This was not disputed by the Norwegians, but otherwise the treaty was declared invalid in Norway – the king's right to cede the country to the Swedish king was not recognised. On the contrary, the right to Norway and its sovereignty had fallen back on the Norwegian people – this is how it was interpreted for Christian Frederick at his first official meeting with selected Norwegians, the so-called ‘Meeting of Notables’ (Notabelmøde) at Eidsvoll outside the capital Christiania on 16th February 1814. The Danish prince's plans to invoke his right of succession were strongly opposed, and he had to align his own plans with Norwegian wishes – and rewrite all his proclamations. Instead of absolute power, it was now decided that a Constituent Assembly would be convened at Eidsvoll, which would then, according to the revised plan, elect the prince as the Norwegian constitutional king.

A hopeful spring: Drafting a new constitution

In Norway, the spring of 1814 was marked by action and hope. Much depended on completing the work on the constitution, which could then be presented as a fait accompli to the outside world – a Norwegian declaration of independence in protest against Sweden's unionist policy. The Norwegian’s strong resistance against the Swedish plans gradually became known in both Sweden and Europe and not least in Great Britain, where the debate about Norway peaked in the spring and summer of 1814. The "Norwegian question" was seen as a difficult and awkward matter by most of the government, because British opinion had a great deal of sympathy for the brave, freedom-loving Norwegian people. Absolutist Denmark, on the other hand, garnered no sympathy, and the new Swedish crown prince was also rather controversial.

At Eidsvoll, an elected national assembly with 112 representatives worked to draft the 110 articles of the Norwegian constitution in the period from 10th April to 17th May. The new constitution stated in the first paragraph that "the Kingdom of Norway is a free, independent and indivisible Realm. Its form of government is a limited and hereditary monarchy". On the same day, 17th May, Christian Frederick was unanimously elected King of Norway. He formally accepted the title on 19th May. Norway once again had its own king for the first time since Haakon VI Magnusson's death in 1380.

A hard autumn: The union with Sweden and the revised constitution

For Norway, however, this success was very fragile, and Christian Frederick’s honeymoon period as King of Norway was quickly over. No one outside Norway recognised him or the country's new position, something the commissioners of the great powers who came to Christiania immediately made clear. By the end of May, Charles John had arrived in Sweden with his army. On 26th July 1814 hostilities began against Norway.

The national optimism of that spring was severely tested, but the war was to be short-lived. Christian Frederick stayed on the defensive and focused on securing the Constitution. Charles John was pressed for time and had little to gain from a lengthy war; the great powers had gathered in Vienna to bring peace and security to Europe, and they did not want a war in the North. The international state of affairs that had helped Charles John dissolve the Danish-Norwegian union in early 1814 were the same as that which forced him to recognise the Norwegian Constitution (with some minor changes) in the autumn of that same year. The Convention of Moss from 14th August saw the Norwegian Constitution being formally accepted, however, the Swedes' counter-demand was Christian Frederick's abdication.

An extraordinary convening of the Storting, the Norwegian parliament, took place in October 1814 to negotiate with the Swedish delegates and make the necessary revisions to the Constitution. On 10th October, Danish Christian Frederick abdicated – also on behalf of his family – and left Norway for good. On 4th November, the revised Constitution was signed, and Charles XIII (born 1748, king of Sweden since 1809) was elected the Swedish Crown Prince. Charles John had achieved his goal of a union on the Scandinavian peninsula. The union remained loose, however. When it was dissolved in a peaceful manner in 1905, Norway finally became an independent state, alongside its Scandinavian neighbours. Yet another Danish prince, Carl (born 1872, king 1905-1957), was elected as King of Norway. By taking the title Haakon VII, he evoked the ancient monarchy of Norway and the last Haakon of Norway, who had been married – it may be added - to Queen Margrete I, founder of the Kalmar union of 1397.

History-telling free of national boundaries can shed light on cultural and historical connections.

This article was published in response to readers' interest in the joint history of Norden.

Further reading:

- Bård Frydenlund, Spillet om Norge: det politiske året 1814 [The scheme for Norway: The political year 1814] (Gyldendal N.F., 2014).

- Rasmus Glenthøj, ed., Mellem brødre. Dansk-norsk samliv i 600 år [Between Brothers. Danish-Norwegian co-existence throughout 600 years] (Gads Forlag, 2016).

- Rasmus Glenthøj and Morten Nordhagen Ottosen, 1814: Krig, nederlag, frihed - Danmark-Norge under Napoleonskrigene [1814: War, defeat, freedom - Denmark-Norway during the Napoleonic Wars] (Gads Forlag, 2014).

- Rasmus Glenthøj and Morten Nordhagen Ottosen, Experiences of War and Nationality in Denmark and Norway, 1807-1815 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

- Ruth Hemstad, Den dansk-norske skilsmisse 1814 [The Danish-Norwegian Separation 1814] (Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2023).

- Ruth Hemstad, Propagandakrig - Kampen om Norge i Norden og Europa, 1812-1814 [The Propaganda War - The Battle for Norway in the Nordic region and Europe, 1812-1814] (Novus Forlag, 2014).