Building the Norwegian state in the early 1800s

Norway had little means of governing itself in 1800 as it was part of the Danish realm and ruled from Denmark. This changed in 1807 when the outbreak of war made communication with Copenhagen difficult and a domestic governing body was appointed. Norway found that it was quite capable of ruling itself and, by 1814, the necessary institutions and expertise were in place for it to cope with independence from Denmark. This did not necessarily make ruling easy, however, because the state finances were in ruins and the country began a union with Sweden.

In the year 1800, only the army could be considered a national institution that was based on Norwegian soil, but even that was not wholly united: At that time, Norway was divided admininistratively between the ‘sønnafjelske’, the Southern part, and the ‘nordafjelske’, the Northern part.

Norway ruled without Copenhagen from 1807

The situation only changed in 1807 when Frederik, Crown Prince of Denmark at the time, saw that it was necessary to establish a way of governing Norway from Christiania (now Oslo). The outbreak of war between Denmark-Norway and Great Britain meant that communication between Denmark and Norway had became challenging. A body to govern Norway during the war was subsequently set up (regjeringskommisjon), which allowed the Norwegians to gain experience in ruling. The three years during which this body was active confirmed that it was possible for Norway to govern itself as a state without referring to Copenhagen.

After Frederik became king in 1808, he began to fear that the regjeringskommisjon might develop separatist ideas, so in 1810, he replaced it with a governor-general directly under him.

The first Norwegian government since the 16th century

The first governor-general of Norway was Friedrich of Hesse, but it was really the second governor-general, Prince Christian Frederik, who showed that a governor in Norway could also act independently. He carried out reforms based on Norwegian needs, and as soon as the process that led to the formation of the national assembly and the constitution began, he formed a government council with seven departmental leaders. This was the first Norwegian government since the riksråd or Council of the Realm was dissolved back in the sixteenth century.

However, Prince Christian Frederik had to step back from governing due to the Convention of Moss in 1814, a convention which marked the end of the war between Norway and Sweden and the starting point of the negotiations over a union between the two countries. In the agreement, Sweden recognised the Norwegian Constitution and the Storting (the Norwegian parliament) for the first time. In the period between Christian Frederik giving up control until the union with Sweden was adopted in November of that year, the Norwegian government took control of the country.

Norway’s union with Sweden: A difficult start

The union made restructuring necessary and a Swedish governor was to lead a Norwegian government department in Christiania. Although several new Norwegian ministers were appointed, some were allowed to continue and the state leadership maintained a certain level of continuity throughout the year 1814. The new Norwegian state did not start from scratch: The state's top civil servants had a lot of experience with public administration and, from the very beginning, they managed to carry out the tasks of state quite efficiently.

But the country's finances were ruined by the long period of war, Napoleon’s blockade against the United Kingdom as well as inflation. It was among the first goals of the administration to establish a Norwegian bank, manage monetary policy and control government debt. With Finance Minister Count Wedel Jarlsberg in the lead, the authorities managed to gain control of the finances through heavy taxation, strong savings and favourable borrowing.

Little pomp and ceremony

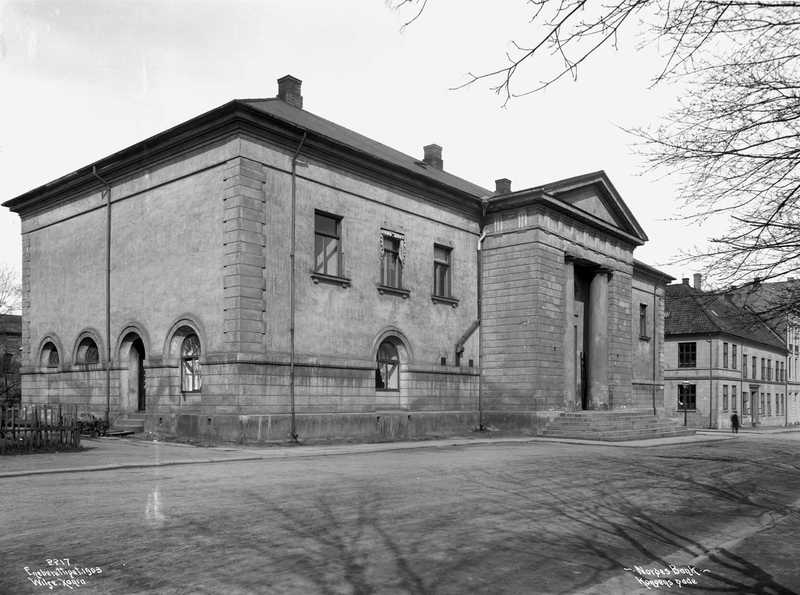

The crisis of the state economy meant that the new Norway could not afford impressive state buildings. At the same time, the capital Christiania was not built with national institutions in mind; there were no government buildings, parliament halls or appropriate places for the Supreme Court. There was a royal residence, but it was a long, low-rise former private house, not even close to the symbol of power of its equivalent in Stockholm. A Royal Palace, ordered by the Swedish (and later Norwegian) King Charles XIV John (Karl d.14 Johan) was not to be completed until almost 25 years later, after his death. For almost 40 years, the Storting had to meet in the cathedral school's ballroom. The state also prioritised institutions such as Gaustad Hospital, the first specialised metal hospital in Norway, and Botsfengselet, the national prison at that time, which both opened long before the Storting got its own building in 1866.

A frugal state

In the first decades after 1814, the Norwegian public sector appeared to be very frugal and cautious with government spending, and the Storting was in charge of the finances. When a Minister of State, Jonas Collett, in a spirit of optimism ordered two modern steamships at the state’s expense without asking the Storting in 1825, there was an uproar and legal action was taken against him.

From a strategic economic perspective, the policy of retrenchment probably continued for too long. However, caution was politically wise: Both farmers and merchants were sceptical of government spending. In a period of stagnation, strict economic policies dampened the conflict of interest between the state and its citizens. In the long run, it may have created greater trust between the state and the Norwegian people than could be found in many other countries.

Further reading:

Links:

- Thanks go to norgeshistorie.no. The original and associated articles can be read in Norwegian by clicking here. It was translated into English by the nordics.info team.