Nordic Labour Markets

Nordic Labour Markets

On this theme page, you can find articles and films about the Nordic labour market(s).

National labour markets in the Nordic countries combine high levels of labour force participation with excellent systems of unemployment compensation and wage differentials are generally low. Nordic labour force participation rates are among the highest in the world, reflecting the primarily higher female labour force. However, the gap between the Nordic countries and the rest of the EU and the United States has been diminishing over the past decade.

The background and history to labour markets in the Nordic countries

In an article on the history of the labour movement, you can read about national Trade Union Confederations rising to prominence in Denmark, Norway and Sweden in the 19th century. However, the mid-19th century also saw migration from Norden, to for example the US, often to do with reasons of labour: 'Push factors' included, for example, limited farming opportunities and 'pull factors' included the promise of cheap or free land.

At home, trade unions gained major influence on the Nordic countries’ political development. In Denmark, the principle of collective bargaining was institutionalised with the September Agreement in 1899 and, thereafter, the other Nordic countries followed suit and adopted similar systems, cementing the structure of corporatism. In 1897, a Scandinavian Conference of Workers in Stockholm formed independent trade unions in all countries, removing direct Social Democratic influence over the trade unions. The political wing of the movement did not merely seek increased unionisation, but also greater equality as manifested in the struggle for universal manhood suffrage.

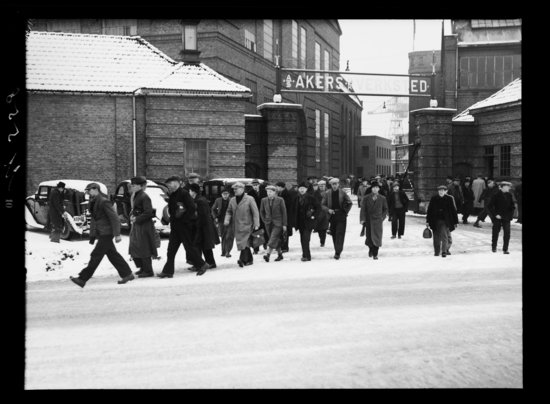

PICTURE: Workers leaving 'Arker Mek' in 1939, a workshop and shipyard in Oslo from 1841-1982. Picture retrived from The National Library o Norway (Nasjonalbiblioteket). Public Domain.

Solidarity, cooporation and flexicurity: 20th century

The labour movement also played a crucial role in the success of Social Democratic parties throughout the twentieth century; work and full employment was an espoused aim for these political parties.

More specifically to Sweden, you can read about wage earner funds in the 1960s and 70s that had the aim of redistributing profit amongst workers of individual employers or sectors. The Harpsund democracy was the Swedish practice of regular tripartite consultation between government, trade unions and businesses on major policy decisions, something that still takes place in Sweden, as well as in the other Nordic countries. Also, a solidaristic wage policy refers to the practice, noticeably carried out in Sweden during the 1950s, of limiting wages in the most profitable sectors and increasing wages in less profitable sectors, with the intention of achieving more equal wages nationally.

Close cooperation between the Nordic countries meant that workers could freely move between them from 1954. How early economic and labour cooperation came about is set out from a Danish and Norwegian perspective in separate articles, the latter in the article Nordic Cooperation 1947 – 1960: a Norwegian perspective). However, the early dream of NORDEK - a Nordic Economic Union (taken from the Swedish ‘NORDiskt EKonomiskt samarbete’in Swedish) was never realised.

Each of the Nordic countries has had a different relationship with the various European economic and common markets that have existed throughout the 20th century. In an article on economic integration, you can read that, while all the Nordic countries participated in the European Free Trade Area (EFTA) which was established in 1960, their different approaches to the common market became especially visible after the 1970s. Denmark joined the EEC in 1973. Norway planned to join but opted to remain outside the EC after a referendum in 1972. Sweden and Finland did not aim for full membership in the 1970s, but signed free trade agreements with the EEC in the early 1970s. In 1990s, the EFTA countries which remained outside the European Union except for Switzerland

(including notably Iceland and Norway) established the so-called European Economic Area (EEA) giving them access to the EU’s Single Market. Finland and Sweden ultimately became members of the EU in 1995. In 2009, Iceland applied to become a member of the EU, but subsequently withdrew its application. A more detailed historical account of Denmark’s relationship to the EU can also be read in the articles, ‘An overview of Denmark and its integration with Europe, 1940s to the Maastricht Treaty in 1993’ and ‘Denmark’s relationship with Europe since 2000’.

PICTURE: The Nordic countries have very different relationships with the European Union. While Finland, Denmark and Sweden are members, Norway, Iceland and the Faroe Islands and Greenland are not. Photo: Sara Kurfeß, Unsplash.

Corporatism is still prevalent in the Nordic countries, where, for example, interest organisations for both employees and employers are involved in tripartite discussions and negotiations in order to inform governmental policy formulation. This consultation reflects the importance of the major interest organisations in shaping and implementing policy, the assumption being that strong policy can be built on consensus between parties that may traditionally be deemed to have opposing interests.

The influence of trade unions also persists today, as more than 80% of all employees are covered by collective bargaining agreements negotiated between trade unions and employer confederations. Some may expect the state to have more influence on labour market actors, however, the value of allowing unions and employers - rather than national parliaments - to determine their own relationships has continued to be recognised in the Nordics throughout the 20th century and still is to this day. Since the 1970s, however, the labour movement has declined, something which can be be attributed to many things, such as the challenges of populism and by the left’s focus on other issues, such as feminism and discrimination.

Nordic labour markets: bringing it up to date

You can read about the economic development of the Nordic countries and the Nordic ‘model’ of capitalism. These countries are today among the richest countries in the world measured by GDP per capita and come top in more or less every international comparison of competitiveness. However, they do not resemble the ‘textbook model’ of efficiency as they tend to have large public sectors, extensive and generous welfare systems, and a high level of taxation in the Nordics.

In the article on labour markets in the Nordics, you can read about how Nordic labour participation rates are among the highest in the world and that unemployment rates are generally low. Unemployment compensation is generally designed to provide a safety net, compared to other parts of the world at least, and active labour market policies are important; work is considered valuable to society and individuals. It is not assumed that the market is a self-equilibrating system in which everyone seeking work will ultimately find a job and active measures are taken to help them.

Trade union membership remains high in all the Nordic countries, especially because union membership in Denmark, Sweden and Finland is – on the whole – still linked to the unemployed compensation system (the Ghent system). However, unemployment compensation schemes that are independent of trade unions are becoming more common and, with specific reference to Finland, there is an article about how precarious workers often prefer these schemes as they are cheaper. The unemployed compensation systems also relate to the concept of flexicurity, a welfare state model that combines a flexible labour market with security and benefits for workers.

Available research on Nordic labour markets continues to be rich and varied, and we host an increasing number of up to date articles on policy and workplace issues. For example, you can read about how employment and unemployment rates have influenced immigration policy in Denmark specifically in the latter part of the 20th century, which still has ramifications today. Another example is when organisational challenges can mean staff resort to making quick decisions about clients that are more likely to be influenced by racial bias in Swedish Welfare institutions in the 21st century.

Critical perspectives also include the continued gender segregation in the Nordic labour markets. In fact, the Nordic countries have greater horizontal segregation levels than the rest of the the European Union, which means that the highest proportion of women work in different sectors than men. Men dominate the private sector whereas women are overrepresented in public sector jobs. The segregation levels have been historically stable, although small increases of women in male-dominated professions have taken place in recent years.

Here is a list of articles, in the order that they have been published, that are to do with the Nordic Labour Markets theme:

The Nordic region introduced free movement of workers already in 1954.

Further reading

- Anders Kjellberg, Den svenska modellen ur ett nordiskt perspektiv: facklig anslutning och nytt huvudavtal [The Swedish model from a Nordic perspective: unionisation and the new main agreement] (Stockholm: Arena Idé, 2023).

- Anders Kjellberg, The Nordic Model of Industrial Relations: comparing Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden (Cologne: the New Trends and Challenges in Nordic Industrial Relations conference, 2023).

- Anette Borchorst, ‘Woman-friendly policy paradoxes? Childcare policies and gender equality visions in Scandinavia’ in Kari Melby (ed) Gender Equality and welfare politics in Scandinavia – the limits of political ambition (Bristol: The Policy Press, 2008).

- Bernhard Ebbinghaus and Jelle Visser. Trade Unions in Western Europe since 1945 (London: Macmillan, 2000).

- Eric S. Einhorn and John Logue, Modern Welfare States: Scandinavian Politics and Policy in the Global Age (New York: Praeger, 2003).

- Eric S. Einhorn and John Logue, ‘Can Welfare States Be Sustained in a Global Economy? Lessons from Scandinavia’Political Science Quarterly, 125, 1 (2010), pp. 1-29.

- Norbert Götz, ‘Century of Corporatism or Century of Civil Society? The Northern European Experience’, in N. Götz and J. Hackmann, eds., Civil society in the Baltic Sea region (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003).

- Søren Kaj Andersen, Jon Erik Dølvik and Christian Lyhne Ibsen, Nordic Labour Market Models in Open Markets, Report 13 (Brussels: European Trade Union Institute, 2014).