Denmark’s relationship with Europe since 2000

Denmark has been characterised by a ‘soft’ type of Euroscepticism. There are multiple institutional safeguards in Denmark to allow for selective participation in European integration, such as, safeguards in its Constitution with respect to delegating power, and a parliamentary committee which has oversight over decisions in Europe. The relationship between Denmark and the European Union since 2000 has involved a (failed) referendum on the accession of Denmark to the single currency in 2000 and a (failed) referendum in 2015 to get rid of Denmark’s four reservations.

2000 referendum on single currency

The implementation of the third stage of the creation of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and the introduction of a single currency in the EU member states in early 1999 required the determination of Denmark's future relationship with EMU. In the spring of 2000, the government decided to hold a referendum on the accession of Denmark to the single currency. Supporters of the introduction of the euro were represented by the major political parties and enjoyed the support of trade unions and entrepreneurs. Nevertheless, at a referendum on September 28, 2000, 53.2% of the electorate voted ’against’ the introduction of the euro, while 46.8% voted in its favour; the turnout reached 87.6%.

There are several explanations for why the supporters of the common European currency in Denmark were defeated. Despite the external agreement between the political parties that advocated the introduction of the euro, the motives and means of their implementation were different. Arguments about the economic benefits of introducing the euro put forward by the proponents of the single currency were not convincing enough in the light of the economic recovery in Denmark at that time and the stability of the national currency. Moreover, the referendum coincided with a record depreciation of the euro and a fuel crisis in many European countries. In this context, the slogan of opponents of the euro, led by the chairman of the Danish People’s Party (Det Danske Folkeparti) Pia Kjærsgaard, appeared to be more convincing: “You know what you have, but you don’t know what you will get”. Also significant was the lack of confidence in the Prime Minister, Paul Nyrup Rasmussen, who supported the introduction of the euro, after he had broken an election promise not to amend the pension system.

Denmark did not take part in the third stage of the EMU and thus maintained the Danish krone as the official curency. The Danish krone is however closely pegged to the euro. Photo: Sara Kurfeß, Unsplash, Public Domain.

Despite the differences between the political parties regarding the integration into the EU, the country's official foreign policy line with regard to European integration was formed by a broad consensus between the parliamentary parties. Some examples include, but are not limited to:

- the general document on Denmark's approach to the Convention on the Future of Europe (Ét Europa – mere effektivt, rummeligt og demokratisk: Konventet om EU’s fremtid, 14. marts 2003);

- the political agreement of November 2, 2004 between the Liberal Party, the Conservative People’s Party, the Social Democratic Party, the Socialist People’s Party and the Social Liberal Party, which determined the areas where the EU could make decisions by means of a Qualified Majority Vote. It was agreed that this procedure would not apply to foreign and security policy, namely, that Denmark would not delegate power to the Qualifed Majority Vote procedure and its explicit agreement would be required (politisk aftale mellem Regeringen (Venstre og Det Konservative Folkeparti), Socialdemokraterne, Socialistisk Folkeparti og Det Radikale Venstre om Danmark i det udvidede EU, Den 2. November 2004)

An established consensus between the political parties regarding the EU was hampered, however, by the new government of liberals and conservatives, who came to power in November 2001, and who had to rely on the Danish People’s Party in order to have a parliamentary majority. The 2001 government platform stated that “the government considers the four reservations to be contrary to Danish interests” (Platform for Government 2001 (Regeringsgrundlag 2001)). The 2003 revised government platform also specified that “the conditions conducive to the adoption of reservations have undergone significant changes since 1993, when they were adopted. Therefore, the government wants the population to have the opportunity to express their position again in one or more referenda, when the time is right for this” (Supplementary Platform for Government 2003 (Supplerende regeringsgrundlag 2003, p. 26)).

The main difficulty for the government was caused by the reservations that prevented Denmark from participating in the discussion on foreign policy issues within the EU. For example, in practice, the representatives of Denmark did not take part in the discussions relating to the new EU constitution or issues of common policy and security due to the presence of these reservations.

Parliamentary control over Danish decisions on the EU

According to the MP from the Social Liberal Party from 1984–2000 J. Estrup (who had been a member of the Committee on Foreign Affairs (Udenrigspolitisk udvalg) for 12 years), the recent Danish Constitution (1953) did not provide for the involvement of Denmark in such close economic and political cooperation as the European Union.

For instance, one of the most discussed issues has been §20 of the Danish constitution “On the delegation of sovereign powers to international organizations in order to promote the development of international law and order and cooperation”. In the absence of consensus between the government and the Danish parliament (Folketing) regarding the participation of Denmark in international integration, this issue requires a national referendum.

In this regard, some researchers tend to emphasize a particular role of nation as a subject of international relations: As a small nation-state, Denmark especially values its sovereignty and is therefore reluctant to transfer powers to supranational bodies. The referendum has become one of the key components of the mechanics surrounding the formation of Danish foreign policy, since section 2 of § 20 of the Constitution obliges the government to hold a referendum whenever the transfer of sovereign powers to an international body is not supported by a majority of 5/6 votes of the total number of members of the Folketing.

In 1996, a group of Danish lawyers sued the then Prime Minister Poul Nyrup Rasmussen for the fact that, in their opinion, the accession to the Maastricht Treaty was contrary to the Constitution, since the treaty opened up opportunities for far-reaching political changes that were not agreed upon by the government. The Supreme Court delivered its decision on April 6, 1998, in which it was stated that accession to the Maastricht Treaty did not violate §20 of the Constitution, which provides for the transfer of powers to interstate bodies “to a certain extent” (“i nærmere bestemt omfang”).

The Danish parlament Christiansborg in Copenhagen. Photo: News Øresund, Johan Wessman, CC BY 2.0. Wikimedia Commons, Public Dommain.

The European Committee (Europaudvalg) is the most influential committee in the Danish parliament, created in 1961 as Common Market Committee (Folketingets Markedsudvalg), it was originally responsible for the preparation of Denmark's accession to the EEC. The subsequent integration of Denmark into the European Communities and the strengthening of the powers of this Committee led Prime Minister Anker Jørgensen to call it “mini-Folketing” (mini-Parliament). In 1994, shortly after the creation of the EU, the committee was renamed into the European Committee (Europaudvalget).

Section 6 of the Law on Denmark's Accession to the European Communities obliges the government to notify the European Committee of decisions being planned in the Council of Ministers that may be directly applicable in Denmark or the implementation of which requires the participation of Folketing.

This means that the European Committee has the authority to issue a mandate to the government for negotiations in Brussels, making it a vital insurance against possible mistakes of the government, thereby filling the “gap” in the Danish Constitution.

In practice, the European Committee limits the freedom of action of Denmark’s representatives in the EU Council of Ministers of the EU, who are guided by the Committee’s mandate when making decisions. The government is also required to consult with the European Committee on the most important issues related to economic policy. Before participating in negotiations on the most significant decisions, the government verbally notifies the Committee of its proposals. If the majority of the Committee supports this proposal, the government will negotiate on its basis.

According to § 15 of the Constitution, a parliamentary majority may dismiss the government. Since the government, which does not secure the support of the parliament, always runs the risk of a vote of no confidence, in practice, parliamentary committees perform not only a monitoring, but also an advisory function, allowing the government to test the ground before making any important foreign policy decision and to avoid an internal political crisis.

2015 referendum

In 1993, Denmark acceded to the Maastricht Treaty with four reservations securing its refusal to:

- introduce a single European currency in Denmark;

- participate in the formation of a single foreign and security policy;

- introduce a common European citizenship; and

- introduce cooperation at the supranational level in the fields of justice and internal affairs.

In 2015, the government led by the Liberal Party (Venstre) held a popular referendum on the cancellation of the reservations. This was to follow up on its earlier election promises stretching back to 2001 to do everything possible to cancel them. As a result, 53% of the Danish population voted ‘for’ preserving the opt-outs, in spite of the Paris terror attacks earlier that year and increasing pressure from the refugee crisis, two key topics seen as factors by the political establishment in favour of closer cooperation with the EU and cancelling the opt-outs.

PICTURE: Poster from the Danish Peoples Parti (Dansk Folkeparti), saying: "More EU? No Thanks". The poster was a part of their Eurosceptic campaign in 2015. Photo: Finn Årup Nielsen, CC BY-SA 4.0. Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

2020s: maintaining its ‘soft’ Euroscepticism of the last 50 years

Despite traditionally having a significant number of Eurosceptics, Denmark’s EU membership is not in question at the beginning of 2020. This allows the Danish historical version of Euroscepticism to be classified as “soft”, which can be defined as having a negative attitude to certain aspects of cooperation, but with a positive attitude to EU membership in general. “Hard” Euroscepticism, on the other hand, is typical of the states that do not consider membership in the EU or would like to withdraw from it. Danish Euroscepticism has generally been focused on the prevention of the transfer of sovereignty to supranational structures, while participation in other areas of integration has been supported.

Denmark remains an active supporter of economic globalization and liberalization and is directly involved in such areas of integration as the common market and the elimination of barriers to transnational trade ( so-called ‘negative integration’). Regarding so-called ’positive integration’, Denmark advocates for the EU's Common Agricultural Policy, environmental protection and consumer protection.

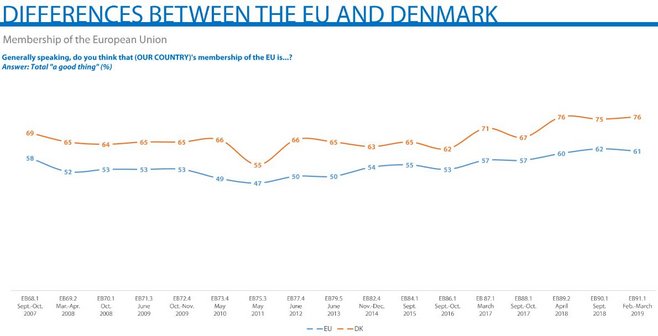

Support for Denmark's membership of the European Union has grown significantly in recent years. As shown in the graph above, 76% of Danes think the membership is "a good thing". The blue line demarcates the average European attitude. Statistics provided by Eurobarameter, the European Union's official polling agency.

Further reading:

- Jørgen Estrup, Uden kompas – dansk udenrigspolitik efter 1945 [Without compass – Danish foreign policy after 1945] (København: Gyldendal, 2001).

- Lizaveta Dubinka-Hushcha, Foreign Policy of Denmark (1972-2012), PhD dissertation (Minsk: Belarusian State University, 2014).

- Matt Qvortrup, 'How to lose a referendum: the Danish plebiscite on the Euro', The Political Quarterly, 72, 2 (2002), pp. 190-196. Niels Amstrup, Dansk udenrigspolitik [Danish foreign policy] (Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1977).

- Uffe Østergaard, 'Danish national identity: between multinational heritage and small state nationalism', in Denmark’s policy towards Europe after 1945: history, theory and options, ed. Hans Branner and Morten Kelstrup (Odense:University Press of Southern Denmark, 2000)