The 1878 Fireburn uprising in the Danish West Indies

Even after the abolition of slavery in 1848, conditions for workers in the plantations of the Danish West Indies did not materially improve. This led to unrest and the Fireburn uprising on St. Croix in 1878. The events of the uprising have been little studied, partly due to the relevant records being in Danish. But the uprising has become significant in the history of the island, particularly in colonial and post-colonial narratives such as that of ’Queen Mary’.

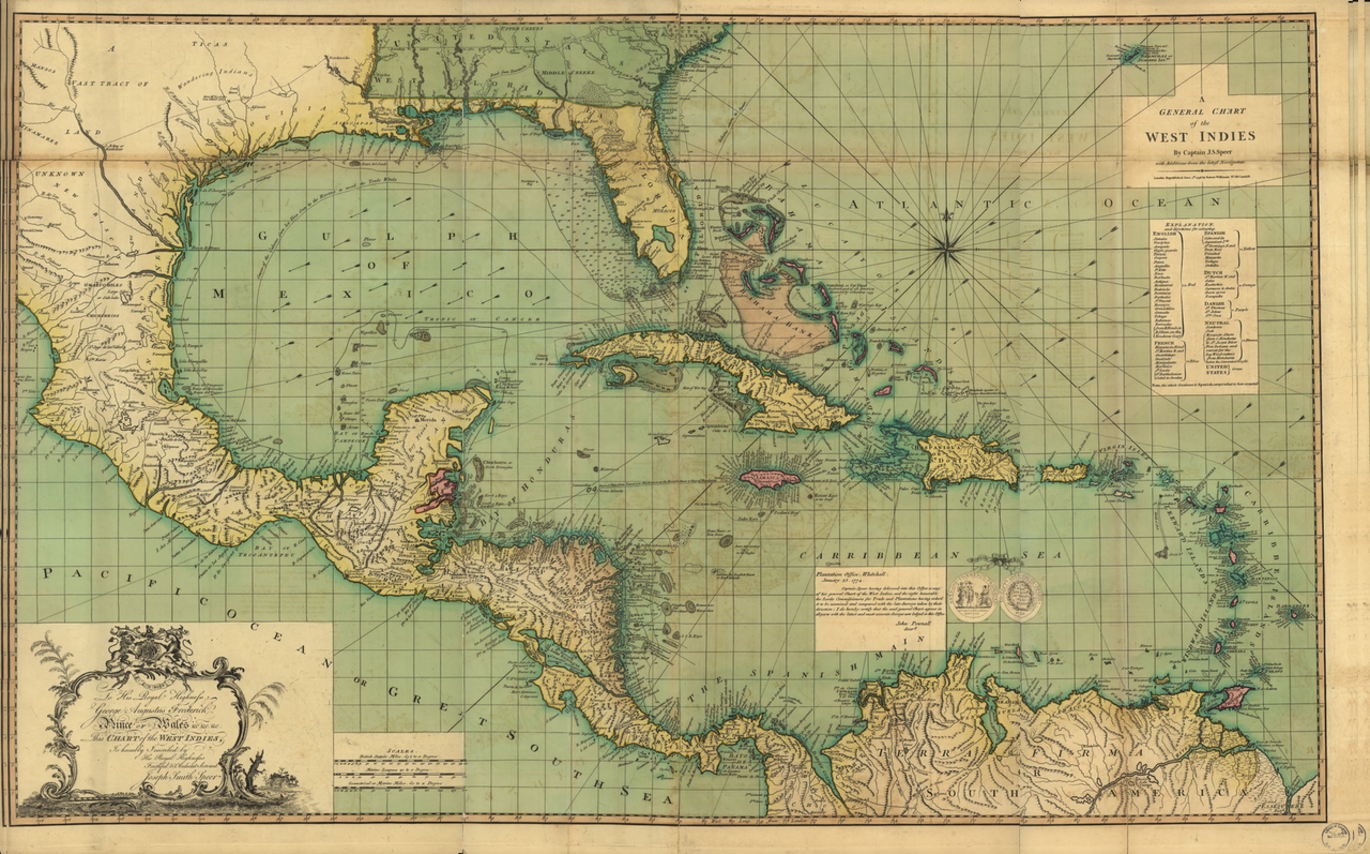

The Danish West Indies and their plantations, 18th century onwards

Denmark, which at the time included Norway, had colonised three islands in the West Indies by 1733, namely, St. Thomas, St. John and St. Croix. St. Croix was the most suited to sugar production as it was relatively flat, although there was also some production of sugar, tobacco and cotton on St. John. Labour at the sugar plantations was based on the slave trade involving African people being bought on the West coast of Africa (from the Danish Gold Coast, what is now part of Ghana), and transported across the Atlantic. It is estimated that around 100,000 people were transported in this way in Danish and Norwegian ships.

In 1792, Denmark passed a law setting out that the transatlantic slave trade was illegal, although it was not due to come into force until 1803. The ten-year period between the passing of the law and it coming into force saw an increase in the numbers of people enslaved and transported. Even after this date, slaves could still be bought and sold on the islands themselves.

Abolishing slavery

Slavery in the Danish West Indies was theoretically abolished in 1848. The dominant historical narrative is that the Danish-appointed governor-general Peter von Scholten declared all slaves free with immediate effect after a labour revolt in Frederiksted on the island of St. Croix involving over 8,000 people. Some scholars question the frequent positioning of von Scholten as the main actor in abolishing slavery as it can potentially diminish the role of other key actors, not least the enslaved. In any event, it became clear during the following decades that there was no meaningful change in the lives of the labourers. This was despite new regulations specifying that enforced labourers had the right to earn a wage, to use a house and a plot of land. However, under the regulations, they were only able to change their job once a year on 1st October, known as ’Contract Day’. Unfortunately, these supposedly temporary regulations went on for over 30 years, and the wages (which were fixed throughout this period) were non-negotiable, so apart from the 'labourers' earning a nominal wage, very little changed.

<

A drawing from the Danish magazine Illustreret Tidende reporting on the fireburn uprising in November 1878. The National Museum of Denmark. Public Domain.

The Fireburn uprising

On 1st October 1878, on the one day of the year that workers could change their workplace, unrest began that led to the Fireburn uprising. The events that day have been little studied and there are differing versions. One popular narrative is that the rebellion can be particularly attributed to three women: Mary Thomas, Axeline Elizabeth Salomon (called Agnes), and Mathilda McBean. There is also a narrative that suggests that some women were burned alive by the Danes as revenge against the rebelling slaves. However, there are also witness accounts to suggest that their death was an accident due to the slaves spreading the fire. It appears to be clear, though, that about 100 protesters were killed, who were mostly shot when fighting with the military, and two soldiers and one plantation owner lost their lives on the side of the authorities. The protesting workers set fire to Frederiksted (over half of which was burned down) and about 50 plantations, including many sugar mills and crops.

12 men were subsequently given a death sentence and immediately shot. 40 people were later convicted, including three women (who later became known as the ’three queens’). Most were convicted for having participated in an active way in the uprising and around one in four were convicted for having been leaders. They were all given the death sentence, but were pardoned by the Danish King and instead received either life imprisonment or were imprisoned ’on the King’s mercy’. Seven were transported to Denmark, including four women. These were the three ’queens’, along with another woman called Susanna Abrahamson. They were imprisoned in a women’s prison in Christianshavn from 1882-1887, after which they were moved to Christiansted on St. Croix.

While the rebellion led to a slightly higher wage, the struggle for better conditions and human rights continued. Around the time of the First World War, the workers began to organise themselves using strikes to demand better conditions. In 1917, the Danish West Indies were sold to the United States of America for 25 million dollars.

Narratives of the Fireburn uprising live on

The three women, Mary, Agnes, and Mathilda, symbolise opposition to colonial power and slavery and enforced labour. Statues of them have been erected in what is now the US Virgin Islands, as well as a highway being given the name Queen Mary Highway on St. Croix. The three ’queens’ have also been depicted in several works of art. A statue of Queen Mary by St. Croix-based visual artist La Vaughn Belle and the Danish-Trinidadian visual artist Jeannette Ehlers was erected in Copenhagen in 2018, marking 100 years since the islands were transferred to the Americans. The monument ’I Am Queen Mary’ is not only a monument to honour the historical person, but to honour opposition to colonialism and racism more generally and has arguably led to a newfound interest in the event in Denmark. Previously, awareness of this event had been scarce and and traditional historical research focused on colonial administrative sources where the Danish view dominated, rather than that of the labourers and rebels in the West Indies.

| One popular narrative is that the uprising was organised by three women, dubbed 'Queens'. This drawing of 'Queen Mary' carrying a sugar knife and a torch was drawn by Ch. E Taylor and published in 1888. Wikimedia Commons, Public domain. |

| The statue 'I am Queen Mary' was created by the two artists La Vaughn Belle and Jeannette Ehlers, and erected in Copenhagen in 2018. Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0. |

| This monument showing all three 'Queens' is located in Charlotte Amalie, St. Thomas. Photo: Linda L. Kung. Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0. |

Further reading:

-

Astrid Nanbo Andersen, 'The reparations movement in the U.S. Virgin Islands’ The Journal of African American History 103, no. 1-2 (Winter/Spring 2018) pp.104-132.

-

Helle Jørgensen, Myte: Var Danmark det første land, der ophævede slaveriet? [Myth: was Denmark the first country to abolish slavery?] danmarkshistorien.dk, 2014.

-

Niels Brimnes, De Vestindiske Øer, 1672-1917 [The Danish West Indies, 1672-1917], danmarkshistorien.dk, 2018.

-

Samantha Nordholt Aagaard, "En af de værste Hovedmænd" Lederskab under oprøret Fireburn i Dansk Vestindien, 1878, ['One of the worst Headmen” Leadership during the Fireburn uprising i the Danish West Indies, 1878'] Master’s Thesis from the University of Copenhagen, 2018.