How Nordic is Estonia?: An overview since 1991

Given Estonia’s history and its geographical location, it is not surprising that it is an obvious trade and cultural partner for the Nordic countries. In 1992, shortly after Estonia gained independence from the Soviet Union, it received observer status at the Nordic Council along with Latvia and Lithuania. Nordic connections since then have included Estonian ex-President’s Toomas Henrik Ilves’ efforts for nordification and the FinEst Link.

Joint history of Scandinavia and Estonia

The Nordic countries and Estonia have a long history, going back to at least medieval times. In fact, Estonia has been under Scandinavian rule longer than it has been under Russian or Soviet rule. Not every historical or cultural link can be mentioned here, but it can be said that Danish and Swedish rule has left its mark in many place names such as Tallinn, a Danish town and known as Castrum Danorum in Latin. In the nineteenth century, Estonia's national awakening was inspired by the Finnish movement on the northern side of the Gulf of Finland. During the First World War, Estonian activists and authorities gradually gravitated towards Sweden, perhaps an obvious choice for a nation with a long tradition of Nordic associations. At that time, it seems that Estonians could be nostalgic about the ‘good old’ Swedish times – despite Swedish rule having stopped centuries before (Swedish rule lasted from 1561 to 1710) – or at least could feel a sense of longing for their Scandinavian connections. (See Mart Kuldkepp's book from 2014 for more on this). These Scandinavian links were seen as being in stark contrast to other nationalistic movements that occurred around that time and throughout much of the preceeding century. The Soviet years (1944-1991) managed to mainly silence Estonian-Nordic co-operation, but Finland quietly grew in significance for Estonians through particularly its media outlets, which were widely followed in Estonia.

The end of the Soviet Union

When the Soviet Union was about to collapse, the Nordic countries used the Nordic Council of Ministers as a channel for assisting all Baltic countries and particularly Estonia. This was a way of avoiding violating international laws about not interfering in other countries’ domestic policies. A Nordic office was established in Tallinn in the spring of 1991, some months before independence was declared. This was the first step to opening a new channel for cultural and other types of cooperation. The office also marked the first internet connection in Estonia. Later, in 1992, Estonia became an observer country to the Nordic Council together with Latvia and Lithuania, but all three are yet to gain full membership.

The ‘re-nordification’ of Estonia: New opportunities for cooperation

During the 1990s and early 2000s the idea of a ‘re-nordification’ of Estonia became part of a government-driven re-branding policy. One central actor was the foreign minister and later President of the Republic of Estonia, Toomas Henrik Ilves. In 1999 he delivered a speech at the Swedish Institute for International Affairs entitled “Estonia as a Nordic country”. Ilves saw Estonia as a Nordic country mainly due to its protestant heritage and work ethic, which he tied to a high level of innovation, as well as likening the calm and well-organised societies on both sides of Baltic sea. This was clearly an attempt to define a new path for the Estonian modernity project, one which was more neo-liberal and Anglo-Saxon in character. Arguably, it was also an attempt to set Estonia on a path of Nordicity where being 'Nordic' did not necessarily just point to social democracy and a cumbersome welfare state.

Norden breaking out of its original borders?

The post-Soviet era opened new possibilities in Nordic-Baltic co-operation. All three Baltic states are NATO members and Denmark has particularly been a close partner and supporter of the Baltic States when it comes to NATO and defence. Finland and Sweden quickly became important trading partners, particularly with Estonia. At the time the Nordic countries began their open border policy in the 1950s, Estonia could of course not be a part of it. However, after regaining independence in the 1990s, Estonia was able to establish open borders with the Nordics to some extent, mainly through other transnational institutions; Estonia became a member of the European Union in 2004 and joined the Schengen Agreement in 2007. These two key developments made it possible to integrate the Estonian and Finnish labour markets in certain ways, particularly around Helsinki and Tallinn. The Helsinki-Tallinn Euroregion, also known as the FinEst Link, has become a major economic centre in north-eastern Europe, which draws interest as well as investment from Brussels. There is an EU project to link the two cities with a railway tunnel to intensify the co-operation between the two areas even further. Finnish researcher Johan Strang argues that projects like the FinEst Link tend to push Norden across its traditional Nordic boundaries, and closer to bigger transnational institutions such as the European Union and NATO. For example, in addition to its more obvious aims, Nordic defence co-operation can be a tool to draw neutral members (e.g. Sweden and Finland) closer to NATO and its military objectives.

The FinEst Link and similar initiatives also bring into question the traditional boundaries of Norden. In many ways, Tallinn and Estonia may be more important to Helsinki than Iceland. Similarly, the southernmost part of Denmark may be more dependent on Schleswig-Holstein and Northern Germany than Stockholm, not to mention Anglo-Icelandic partnerships, which may be more vital to Iceland than the one between Iceland and Finland. Even among the Nordic countries, many agreements are made bilaterally and not necessarily within the realm of formal Nordic cooperation and, this being so, it is possible to question the precise sphere of influence of the Nordic Council and the Nordic Council of Ministers.

Estonian identity and symbolism

The identity of the Estonian nation has been under speculation both domestically as well as abroad. Certain elements in Estonian society undoubtedly think that Estonian history is very 'Nordic-like', but the country was of course shut behind the Iron Curtain for several decades limiting the extent to which it can be seen as ‘Nordic’. There is a Nordic-Estonia Society and, according to one blog, the term ‘Nordic’ does not only refer to political-economic factors concerning a wealthy and strong economy, but something more cultural. Estonia tends to promote gender equality, compassion and solidarity in a Nordic way. This has been used as another example of cultural and social links and similarities - such as at the 2016 conference ‘Estonia AND the Nordic countries – Estonia AS a Nordic country?’ organised by the Centre for Ethics at the University of Tartu and the Nordic Council of Ministers' Office in Estonia.

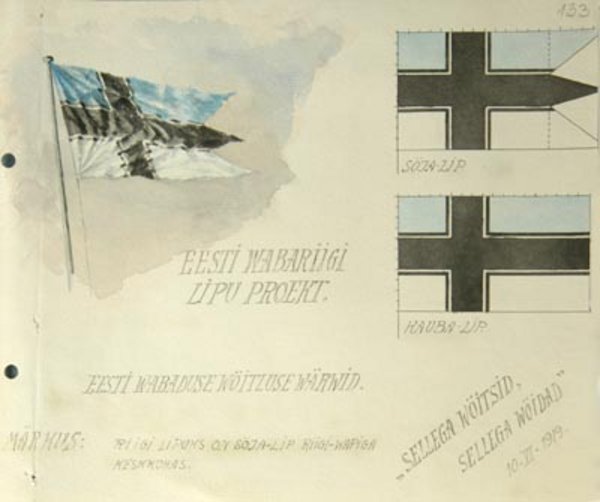

In 2001, there was an important debate surrounding the proposal for a new Estonian flag which would promote the country’s Nordic identity, the existing one having a different design. Advocates for the new design, such as former President Toomas Hendrik Ilves, expressed the importance of these changes to symbolically show that Estonia was closer to the Nordic countries than the Baltic states, and to culturally distance the country from Russia in the post-Soviet era. However, some commentators saw this new design as excluding other important nations, not least Estonia’s Baltic neighbours. The previous president of Estonia, Kersti Kaljulaid (who served as president from 2016-2021), suggested the less radical approach using the term “Nordic-Benelux” to include like-minded countries in Northern Europe. Criticism towards highlighting Estonia’s Nordic identity has tended to concentrate around the country’s cultural and intellectual spheres.

In addition to its Nordic identity, there are of course lots of other competing identities in Estonia, including the Fenno-Ugric, the Baltic and the European. But, as Strang puts it, the Cold War era created several parallel identities, and the Hanseatic identity or Baltic Sea regionalism do not have to be mutually exclusive, but can overlap with Nordicity. In 2013, an opinion poll showed that some 53.3% of young Estonian people considered their identity to be ‘Nordic’, whereas an almost equal number, 52.2%, considered themselves as ‘Baltic’. The poll appears to show a common identification with the Nordic countries, but also how Baltic identity has in all likelihood grown during the post-Soviet years. Nordic identity is often seen in parallel with a Fenno-Ugric identity, particularly between Estonians and Finns.

Regardless of which viewpoint you take, it will be interesting to follow future developments and whether the people of Estonia choose to be more firmly positioned as ‘Nordic’ or continue to weave between different overlapping, regional identities.

Further reading:

- Alyson J. K. Bailes, Denmark in Nordic Cooperation: Leader, Player, Sceptic; Danish Foreign Policy Yearbook (Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016).

- Mart Kuldkepp, Estonia gravitates towards Sweden: Nordic identity and activist regionalism in World War I (Estonia: University of Tartu Press, 2014).

- Johan Strang, Nordic Cooperation – A European region in transition (New York: Routledge, 2016).

Links:

- Norden.ee, 'Estonia AND the Nordic countries – Estonia AS a Nordic country? conference summary and videos (01 September 2016).

- Website Nordic Estonia (about 'Why is Estonia nordic? NordicEstonia.com provides info about what ties Estonia to other Nordic countries.)