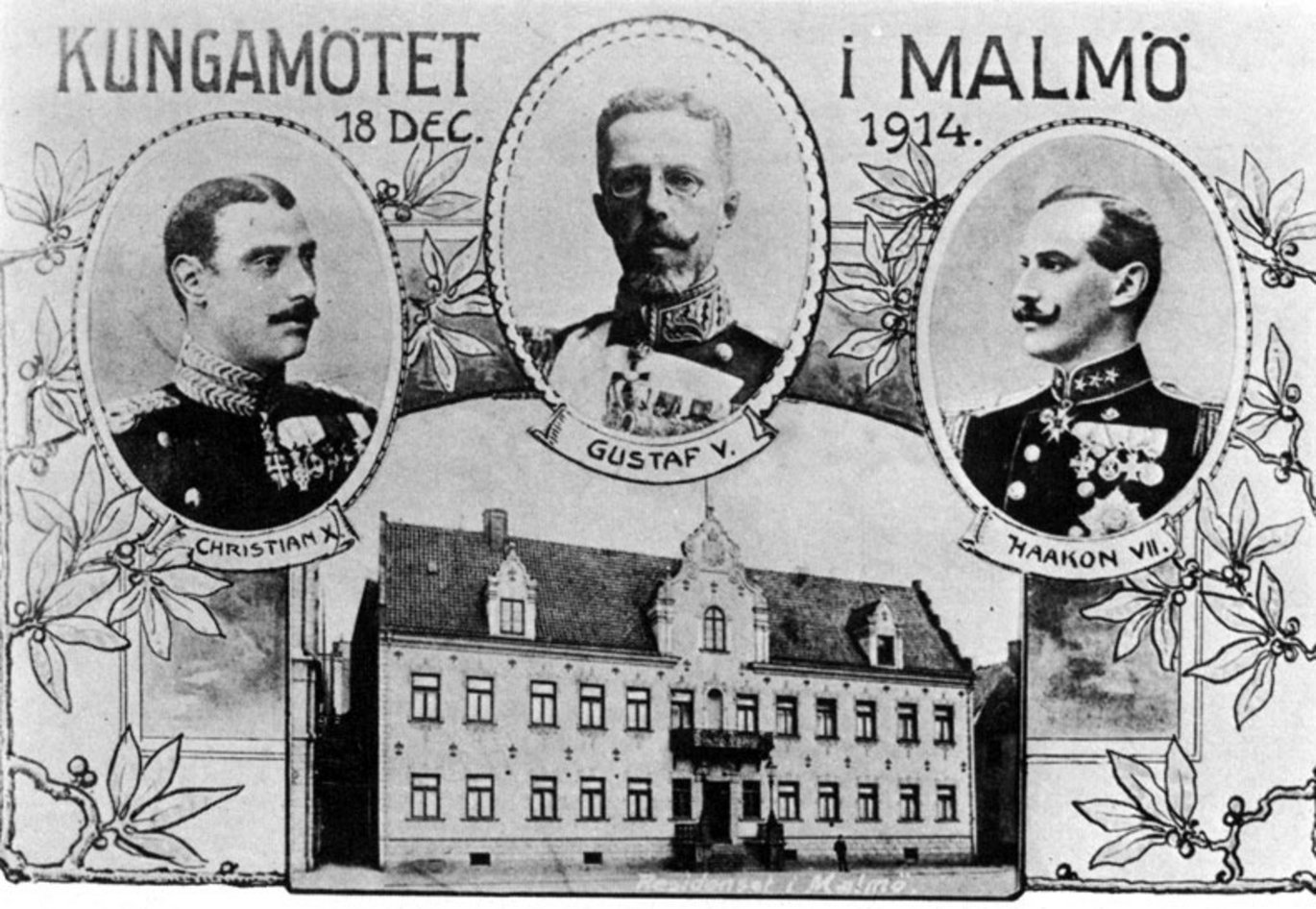

The Three Kings Meeting in 1914

After World War I had been raging for six months and the pressure to choose a side was mounting, the kings of Denmark, Norway and Sweden met to find a common position. On the surface, the meeting was a success - the three countries were united in their neutrality. But, behind the scenes there were bubbling tensions due to differing perspectives on Nordic cooperation and the wider geopolitics of Europe.

Joining forces in the face of international pressure

At the beginning of World War I, every belligerent country was pressuring the Nordic nations to choose a side. Sweden shared a border with Russia, and Denmark with Germany. The Nordic countries were also important trade intermediaries for German imports; buying goods from the Nordic countries allowed Germany to circumvent the blockade imposed by the United Kingdom and France. The German U-boat campaign against British ships also made the Oresund strait between Denmark and Sweden of great importance to both sides. This region was at the heart of the Northern front of the First World War.

Despite their absence at the Three Kings Meeting, the influence of the Great Powers was strong. The British Foreign Secretary E. Grey explicitly asked the British journalists in Malmö to avoid making remarks that could offend the Scandinavians. The British Foreign Office was particularly concerned that its ally Norway would form stronger ties with Stockholm, which could lead to a lessening of the Norwegian’s pro-British foreign policy. The Central Powers were also not to be outdone: Kaiser Wilhelm II gave a message to the Swedish queen (who was visiting Berlin at exactly the same time as the Three Kings Meeting) to give to her husband, Gustaf V, in order to try to persuade him to join Germany’s side.

With each of the Scandinavian states facing such international pressure, this meeting was crucial. The three kings, national figures who could embody each nation on the international stage, held important symbolism, and the meeting was meant as a way of showing – loud and clear – each of the three countries’ solidarity in Nordic neutrality.

A balancing act between world powers

The meeting was also a balancing act between the two sides in the First World War as the three nations did not want to appear too close to either side. This was precisely the international policy which had been conducted since 1909 by C. T. Zahle (1866-1946), the Danish Prime Minister (or the ‘Council President of Denmark’ as the post was officially referred to then). His intention had been to dampen the traditional anti-German feeling that was often part of Danish patriotism at the time, a feeling which stemmed particularly from the Danish defeat in the Second Schleswig War against Prussia in 1864. Zahle’s approach was cautious and accommodating in an attempt to avoid a potential conflict with the powerful German army. The Swedish king, Gustaf V, was seen as pro-German, partly because his wife, Victoria of Baden, was the first cousin of the Kaiser, Wilhelm II. Organizing the Three Kings Meeting was a way for the Swedish king to silence rumors about his germanophilia – despite his wife’s appeasing meeting with the German emperor in Berlin on exactly the same day. She diplomatically expressed that Swedish neutrality did not mean that Sweden was against the Triple Alliance.

Intra-Nordic tensions between Sweden and Norway

The Malmö meeting was the first time King Gustaf V of Sweden and his Norwegian counterpart met, and this was particularly significant as Norway had only become independent from Sweden 10 years before. In 1905, Norway unilaterally dissolved the personal union with Sweden which had begun in 1814, becoming fully independent after a referendum. Norway’s independence came about for many reasons, but one key disagreement with Sweden was its refusal to allow Norway’s previous king (Oscar II, 1829-1907) to represent Norway abroad autonomously. This meant that, in 1914, Sweden was mindful of the conciliation necessary with the Norwegian royal family.

The relationship between the two countries in the 1910s was not warm. The divorce between them just a few years before had marked the end of Sweden's self-conception as a political and military power in Europe, an understanding which went back to the 17th century. The Swedes’ pride had also been jilted by the 1905 separation and the two countries did not enter into a non-aggression pact until 8th August 1914, finally ending the Norwegian conception of Sweden as a potential enemy. For its part, the young Norway was seeking to impose itself on the Nordic stage.

Considering the global geopolitical context more important than national divisions, the Swedes initiated the Three Kings Meeting in order to extend the hand of friendship to Haakon VII. When the Norwegian king received the Swedish proposal, he immediately informed the British Foreign Office, expressing his doubts and fears about a multilateral meeting that could create more friction than traditional bilateral negotiations, a response which demonstrates the climate of distrust between the two Nordic powers at the time.

Sweden’s agenda-setting

By organizing the meeting, Gustaf V intended to show the world that Sweden was a pillar of peace, neutrality and solidarity in the region. In making his counterparts come to him, he made Sweden the symbolic center of the region. Abandoning its idea of being a traditional, realist country after the dissolution of Sweden-Norway, the meeting was part of Stockholm’s realignment of its priorities to become a peaceful power.

The choice of location was also an attempt to be as neutral as possible. In order to circumvent a Norwegian refusal if the meeting was held in Stockholm (the former “imperial” capital), Gustaf V organized the meeting in Malmö, a smaller city near the Danish border. This was also of symbolic value to the Danes as the city was – and still is – influenced by Danish culture and history.

The way the meeting was organized was also intended to lower intra-regional tensions: all the events (patriotic songs, concerts, a church service etc) were to be perfectly balanced between the three countries to avoid hurting any national pride and to put the emphasis on common traits and factors of unity rather than on differences.

In Malmö, the three kings appeared together, united, to show that the divisions of the past were at an end and in order to solemnly unite for peace in the region. It was a ceremonial sublimation of the Nordic countries, of their fraternal and peaceful relations, aimed at a transnational Nordic audience.

Diverging points of view despite outward unity

Despite the united front presented at the meeting, the Nordic region in 1914 was far from homogeneous:

Royal family ties:

Denmark, despite the foreign policy of its Prime Minister, still harbored strong anti-German feeling. This had particularly intensified after Denmark lost a third of its territory in the Second Schleswig War in 1864 to Prussia and Austria. The inclination for the Triple Entente ran in the family of the Danish and Norwegian kings: Christian X was the cousin of the Russian czar Nicholas II and the English King George V, and brother of the Norwegian King Haakon VII, whose wife, Maud of Wales, was the sister of George V. On the other side, King Gustaf V of Sweden had married a German princess, Victoria of Baden, who was cousin to the Kaiser.

Economic and political interests:

Norway was particularly close to Britain due to the importance of its naval trade, which meant that Norway was referred to as the United Kingdom’s “neutral ally” at this time. On the other hand, Norway in 1914 was a really young nation, having only been independent since 1905, and the national discourse was understandably characterized by its origins and what the new nation should look like. Many Norwegian people believed that they shared the same ethnic roots as German people, so Norway was reluctant to enter into a fight with Germany in case it should be divisive on the domestic front. Neutrality was not only a question of foreign interests for Norway, but also a way of maintaining unity among its people.

Sweden’s pro-German faction:

Sweden was politically divided, too. If the liberals and the working class were largely against a Swedish intervention in World War I, the conservatives, especially those close to the king, were in fear of Russia and led a powerful Germanophile faction. In fact, the Swedish delegation at the Three Kings Meeting, which came together with the king, were clearly in favor of supporting Germany.

So, despite appearances, a consensus at the meeting in Malmö was not so easy to find. Ultimately, it was partly thanks to the Swedish Minister of Foreign Affairs, Knut Wallenberg (1853 – 1938), who managed to neutralize the Swedish faction supporting Germany. By choosing neutrality, Gustaf V also secured support amongst Sweden’s largely pacifist domestic working class for the monarchy.

Was the Three Kings Meeting a success?

The Three Kings Meeting definitely warded off World War I extending into the Nordic region to a greater extent than it did otherwise. It clearly presented a peaceful and neutral region - as well as one largely under the leadership of Sweden - to a Europe which was violent and chaotic. Gustaf V’s initiative was clearly an exercise in public relations. It was a way of promoting Swedish “soft power” and of getting the diplomatic leadership of the region back after decades of division.

While the Malmö encounter can be said to be the first time Scandinavian neutrality was first truly asserted and became known on the world stage, this approach did not come out of nowhere. It emerged at the end of the 19th century in reaction to the russification of Finland and to the germanization of South Schleswig. Frightened by Russian and German aggression and aware of their limited capacity for resistance, the idea of neutrality developed favorably in the Nordic countries. It was not only seen as a legal right which every sovereign country had, but as a pragmatic response to the geopolitics of the time.

While neutrality was clearly important to the Nordic countries beforehand, the Three Kings Meeting was crucial to the evolution of neutrality as a key cornerstone of Nordicity, both from a formal and ideological point of view. It signified cooperation among states. It was followed by another meeting in the Norwegian capital in 1917 and, in 1939, the Danish king also used this method of cooperation after the beginning of the World War II. The Malmö meeting had introduced a new form of cooperation between Nordic countries and, according to Ruth Hemstad, the Three Kings Meeting was the starting point of twentieth century interstate Nordic cooperation.

The Three Kings Meeting could also be said to have given new impetus to Scandinavism, an ideology that supported varying degrees of cooperation among the Scandinavian states which had begun in the 19th century. Before the Three Kings Meeting, cooperation was rather fragmented and was made up of different kinds of regional associations and professional communities, especially student ones, but it lacked a unifying dimension. The Malmö meeting offered Scandinavism an overarching and formal solidarity.

Furthermore, the Three Kings Meeting showed a cooperation that was characterized by the importance of peace. It can even be said that the meeting heralded the beginning of the rhetoric of peace and its central role in conceptions of Nordic identity.

Further reading:

- Anders Jarlert, ‘The Myth of Sweden as a peace-power state and its religious motivations’, Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte, 27, 2 (2014) pp. 257-262.

- Michael Jonas, ‘Royal Diplomacy: Three Kings Posturing? Royal Diplomacy and Scandinavian Neutrality in the First World War’, in Scandinavia and the Great Powers in the First World War (London: Bloomsbury, 2019).

- Peter Stadius, ’Trekungamötet i Malmö 1914’ [The three kings' meeting in Malmö 1914], Historisk tidskrift för Finland, 99, 4 (2014) pp. 369-394.

- Ruth Hemstad, 'Scandinavianism, Nordic co-operation, and ‘Nordic democracy', in Jussi Kurunmäki and Johan Strang, eds., Rhetorics of Nordic Democracy (The Finnish Society of Science and Letters; 2010) pp. 179-193.