Red Norden: Scandinavian communist cooperation in the 1920s

The Scandinavian Communist Federation was the Nordic Communist Parties' attempt to establish a climate conducive to revolutionary movements in their respective countries at the beginning of last century.

A different way of looking at the Nordics

The development of the Scandinavian Communist Federation challenges the idea of an exclusive social democratic hegemony during the inter-war years. Communist action in the first half of the twentieth century is often overlooked as Nordic history often focuses on the Nordics as a ‘middle way’ between socialism and capitalism. During the Cold War, for instance, research and commentary understandably focused on the capitalist side. Socialist elements of Nordic cooperation, or even the notion of a purely ‘socialist’ Nordic cooperation, seem unthinkable because Nordic socialism has usually been regarded as having developed without direct links to Soviet socialism - and even, at times, in anticipation of it.

The Scandinavian Communist Federation also challenges the usual perception of the socialist hegemon as the Soviet Union was not generally interested in cooperation among actors in its vicinity due to geopolitical considerations. The social democrats in the Nordic countries, on the other hand, are well-known for cooperating across national borders from at least the 1930s, and they seem to have monopolised the narrative on Nordic cooperation stemming from that time. This may be because the development of Nordic cooperation thereafter has been directly linked to the social democrats, and specifically SAMAK, the Joint Committee of the Nordic Social Democratic Labour Movement (Arbejderbevægelsens nordiske samarbejdskommitté (founded as: Komiteen for den skandinaviske arbejderbevægelses samarbejde)). The communist attempt to form a Nordic movement – which actually preceded SAMAK and was in fact a model for it - is, by contrast, little written about.

The intention of communist cooperation was to establish a climate in which the Nordic Communist Parties could fulfil their “historical duty”: they were to facilitate the revolutionary movement in their respective countries, ultimately ensuring the dictatorship of the proletariat. Such cooperation was institutionalised when the Scandinavian Communist Federation (SCF) was created in 1924, replicating the Balkan Communist Federation. But, how did the SCF come about when there was a multitude of complex and often contradictory factors at play, both in and outside Norden?

The beginnings of Red Scandinavism: a Scandinavian bureau

In 1919, during the seventh session of the Executive Committee of the Communist International (EKKI), it was decided that a Scandinavian bureau should be created to coordinate the communist parties-to-be of Norway, Denmark, Sweden and Finland as, at this point in time, no communist party formally existed. Two things are particularly noteworthy about this decision:

- Firstly, in Norway, it was the Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) that became a member of the Communist International in 1919. This is remarkable because it was the only party that was not merely a splinter section of a Social Democratic Party.

- Secondly, it is unclear why Finland was included in the Executive Committee’s decision as it contradicted the usual application of the term ‘Scandinavia’ at the time; in Soviet discourse, Finland was usually seen as a Baltic country, at least until the end of World War II. For example, the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact of 1939 defines the Baltic territories as Finland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania and thereby subjugates them to the Soviet sphere of influence.

A Danish coup in February 1922

The work of the Scandinavian bureau of the Communist International was most visible during a coup within Denmark's Communist Party. The EKKI tasked the Scandinavian bureau with recommending which of two opposing factions in the coup should be supported - the Scandinavian bureau was not capable of enacting decisions, only of providing a recommendation. Although the EKKI trusted the Scandinavian bureau enough to seek their views on this crucial question - a question which was to set the future ideological course of the young Communist Party of Denmark - consultation with the Scandinavians was not mandatory. The EKKI did in fact enact the recommendation of the Scandinavian Committee and affirmed all its major points. The only point of deviation was the choice of the party’s leader: The Scandinavian bureau was not Bukharinist, but the EKKI appointed a Bukharinist leader as this was a faction which enjoyed the support of the majority of the EKKI at the time.

‘The First Norwegian Question’ in December 1922

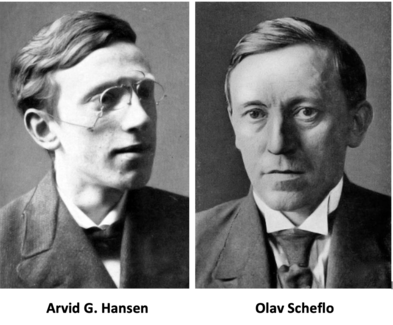

In Norway, the Labour Party was unwilling to accept party members through individual criteria, as demanded by the Comintern. They wanted members to be accepted by collective criteria, as had been the party’s standard previously, such as, through trade union membership. For the Comintern, individual criteria was vital as its was one of the 21 points by which a party was to be considered a “real” Communist Party and eligible for membership in the Comintern. Refusing this condition meant that the Norwegian Labour Party’s membership of the Comintern was problematic, so the EKKI formed a Norwegian commission which dealt with the issue in detail. The commission went on to issue an ultimatum indicating that the Norwegian Labour Party had to stick to the Comintern’s rules. This caused a rupture within the Labour Party leading to the majority of its membership leaving. The Comintern did not look favourably on the situation, and the movement was negatively referred to as Tranmaelism after their leader Martin Tranmæl (1879-1967). The smaller faction, which was based around Arvid G. Hansen (1894-1966) and Olav Scheflo (1883-1943), went on to form Norway's Communist Party in 1923, which shortly afterwards became SCF’s initiator.

The Scandinavian Communist Federation

On 21st of February 1924, the Federation of the Scandinavian and Finnish Communist Parties was founded. Coinciding with the death of Lenin (1870-1924), it did not start its work under a good omen. Even prior to this date, the outcome of the First Norwegian Question had been heavily criticised by the Swedish Communists as it feared losing its decision-making power not only vis-a-vis the SCF but also with respect to the EKKI and its increasing centralisation. Such concerns were not without foundation; the Balkan Communist Federation was being treated as a block and most of the power lay with them at the supranational level - meaing that the parties of the individual countries only had a limited say.

It was during the Fifth Congress of the Communist International in 1924 that the EKKI recognised the SCF and tasked an ‘Organisational Committee of the EKKI’ - or an affiliated body - to come up with an action plan for the SCF within eight days.

The Swedish and Icelandic Questions

In the same session, the Swedish and Icelandic Questions were also negotiated. The Swedish Question may be regarded as a continuation of the Norwegian Question, as individual members had been accused of showing solidarity with the Tranmaelists. The Icelandic Question dealt with the Alþýðuflokkurinn, the Icelandic Social Democratic Party. The final resolution issued by the Organisational Committee of the EKKI stated that the "half-communist" entities of the Icelandic Party ought to seek an alignment of the entire party with the SCF and thereby remove themselves from the influence of the "social-traitors" of the Danish Social Democratic Party. This was based on the Comintern's policy not to form a Communist Party of Iceland but to encourage the Icelandic communists-to-be to use their influence within the Social Democratic Party in order to transform the entire party into a Communist Party. Such was the policy until November 1930, when the Communist Party of Iceland was formed. In relation to the SCF, it meant that the EKKI integrated Iceland, thereby proactively expanding the SCF to include all the Nordic countries.

Only an organisation on paper

The EKKI actually amended the Comintern statutes allowing the communist parties of neighbouring countries to form federations like Scandinavia and the Balkans. Despite this, the SCF's potential was never fully realised. As early as September 1924, Denmark's Communist Party developed akin to the communist parties of Sweden, and Norway before it: debating the decisions of the Comintern to a point were it threatened the party’s unity. Solving such issues through the SCF was impossible and in any event undesired. The EKKI decided to manage the parties directly in order to coordinate the problems themselves, undermining the position of the SCF. Whether this was due to the lack of cooperation of the individual communist parties themselves or stemmed from the EKKI is unclear. Around this time, and at the latest in July 1927, the SCF morphed into the Scandinavian Ländersecretariat. The establishment of the so-called Ländersecretariat was a result of the Stalinisation of the Comintern’s policy and the shift from coordinating semi-autonomous agents to exorting full power over them. In March 1927, Willi Mielenz (1895-1942), the then-secretary of the Scandinavian Ländersecretariat, declared the Federation as "[formally existing], but not in reality".

The Legacy of the SCF?

While the EKKI describes the SCF as well-functioning and only lacking support from national communist parties at the beginning, it was no longer mentioned in any EKKI reports from 1926 onwards. A similar fate of silence met the Balkan Communist Federation, despite an archival record of a congress of the Balkan Federation in 1928. Without further research, it is impossible to say whether the EKKI halted the SCF as it threatened Moscow's status as primus inter pares in the Communist movement and the Scandinavian region in particular, or whether it failed due to a disinterest in Scandinavian cooperation among the national Communist Parties.

The SCF was by no means the first Intra-Nordic communist cooperation, and it was certainly not the last. Nordic cooperation continued as seen on this poster, which concerns a Nordic meeting of the Youth Organisations of the Communist Parties of Sweden, Norway and Denmark. While an exact date for the poster is difficult to determine, given the fact that the SCF did not use the term "Nordic/Nordisk", it must be assumed that the poster stems from the post-SCF era. The inscription KUI seen in the flag indicates that this organisation operated under the Young Communist International, the Communist International’s youth organisation, which was dissolved in 1943. KUI stands here for Kommunistiske Ungdomsinternationale.

Further reading:

- Ainur Elmgren, ’The Socialist Soviet Republic of Scandinavia [Kokkuvõte: Skandinaavia Nõukogude Sotsialistlik Vabariik]’, Ajalooline Ajakiri. The Estonian Historical Journal, 3 (2015).

- Aleksander S. Kan, Nikolaj Bucharin och den skandinaviska arbetarrörelsen [Nikolaj Bukharin and the Scandinavian labor movement]. Opuscula historica Upsaliensia 6. (Uppsala: Historiska Institutionen, 1991).

- Erland F. Josephson, SKP och Komintern 1921-1924: motsättningarna inom Sveriges Kommunistiska parti och dess relationer till den Kommunistiska internationalen. Edited by Sven A. Nilsson, Sten Carlsson, and Carl Göran Andræ. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis Studia Historica Upsalensia 84. (Uppsala: Historiska Institutionen vid Uppsala Universitet, 1976).

- Johan Strang and Jussi Antero Kurunmäki (eds.), Rhetorics of Nordic Democracy (Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 2010).

- Örjan Berner, Sovjet & Norden: samarbete, säkerhet och konflikter under femtio år. (Stockholm: Bonnier Fakta, 1985).

- Mirja Österberg, ‘“Norden” as a Transnational Space in the 1930s - Negotiated Consensus of “Nordicness” in the Nordic Cooperation Committee of the Labour Movement', in Mary Hilson, Silke Neunsinger, and Iben Vyf, Labour, Unions and Politics under the North Star: The Nordic Countries, 1700-2000 (New York: Berghahn Books, 2017).

- Tauno Saarela, Finnish Communism Visited. Papers on Labour History VII (Helsinki: Finnish Society for Labour History, 2015).

- Trine S. Jansen, ‘Komintern Og Dannelsen Av de Skandinaviske Kommunistpartier’, Arbejderhistorie, 3 (2003), pp. 20–44.