Historical Pay Inequalities in Scandinavia

The national implementation of the International Labour Organization's 1951 Equal Remuneration Convention led to significant political disagreements in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, some of which are still relevant today.

Summary: Pay and working conditions in the Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Norway and Sweden) are traditionally negotiated by the social partners (trade unions and employers’ organisations), who come to an agreement via collective bargaining. Governments tend to have a hands-off approach to issues concerning the labour market. This way of working can clash with international law and global norms where national legislation is often expected. The interaction between these different aspects came to the fore in the Scandinavian countries after the historic 1951 Equal Remuneration Convention. Rather than being confined to history, these issues are still very prevalent in equal pay discussions to this day.

Different pay rates for men and women in 1950s

In the Scandinavian private sector of the 1950s, there was a pay rate for men and a separate one for women. This was based on various factors including: the man was the main breadwinner; women were considered less productive than men; and, women were more likely to leave their jobs when they got married, or needed time off to look after sick children. Different pay rates had not been allowed in the public sector since the 1930s, but it should be remembered that the public sector was much smaller than it is today as the welfare state was just on the cusp of blooming.

All was not entirely well in the public sector either, however. While formally the public sector in all countries had adopted the principal of equal pay for the same job positions, women were often placed in lower paid positions without the possibility for promotion. Furthermore, female-dominated care professions (such as nurses or kindergarten teachers) were characterised by having a low wage level when compared with professions with the same level of education. (We now call this latter issue gender segregation, and it is a persistent problem to this day.) Many women also worked part-time or seasonally

1951: International pressure for equal pay

On 6th June 1951, the International Labour Organisation (which had been founded in 1919) adopted the Equal Pay Convention (number 100), which stated that:

“the term equal remuneration for men and women workers for work of equal value refers to rates of remuneration established without discrimination based on sex”.

However, the Convention was unclear about what equal pay for work of equal value legally means. Additionally, states were not obliged to introduce actual legislation to ratify the Convention, they could also choose to leave it up to the social partners to implement, namely, the trade union bodies (usually the LO, the national confederation of trade unions in each of the Scandinavian countries), and the organisations for the employers (usually the respective national confederations of employers.

Scandinavian collective bargaining blocks the implementation of equal pay

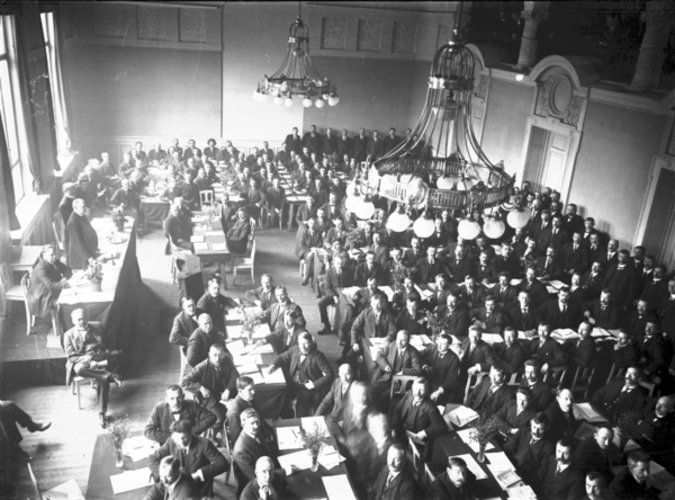

The parliaments of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark went on to debate whether they should ratify the Convention and how equal pay should be implemented. The main difficulty with implementing the Convention by passing an equal pay law was that wages in the private sector in all three countries were determined through the collective bargaining system. This system consisted – and still does – of the workers’ and employers' organisations being responsible for bargaining wages and working conditions, with parliament only intervening if absolutely necessary. The Scandinavian countries also each have a system of separate and independent institutions for handling and settling disputes over collective bargaining agreements. Passing an equal pay law would dilute this self-governing labour market.

An extra layer of pressure to implement the convention came in 1957 when the European Economic Community (EEC, since 1992 the EU/European Union) decided that a country had to implement the principal of equal pay if it wanted to be a member of the federation. This aspect became particularly relevant for Denmark which was keener to join Europe and was the first Nordic country to do so in 1973.

Where did the social partners stand on ratification in 1950s?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the employers’ organisations in all three Scandinavian countries originally opposed the Equal Remuneration Convention. This was because, if women were to make the same amount of money as men, it would result in a significant increase in employer’s costs. Women, after all, were cheap labour. In Norway and Denmark the national confederations of trade unions (‘LO’, Landsorganisasjonen i Norge and Landsorganisationen i Danmark) had supported the Convention from its inception, although historian Inger Bjørnhaug notes that Norway did little to achieve economic equality in general (see further reading for more on this), and in Denmark support was for the most part simply symbolic. In Sweden, neither side – the Landsorganisationen i Sverige nor the Swedish Employers’ Association (‘SAF’, Svenska Arbetsgivareförening) – supported a national ratification throughout the 1950s, and neither did the Swedish parliament. This may have been to do with the larger proportion of women who were working in Sweden at the time compared to the other two Scandinavian countries.

Women’s representation: How were women’s voices heard?

Women’s voices were heard through their membership of trade unions and subsequently the national confederations, and likewise theoretically through employers' organizations. However, women were underrepresented generally in each of the tripartite wage bargaining bodies, including of course parliament. In the mid-20th century, there were few Danish, Norwegian and Swedish women in leadership positions, this included politics, business, and powerful organizations such as LO. Women therefore established and gathered in different women's organizations. Some were affiliated to the respective LOs and had, since the early 1940s, mobilised and discussed gender-specific issues in the Norwegian LOs Kvinnenemnd and the Swedish LOs Kvinnoråd, for example. Both organizations later claimed that the fight for equal pay between genders was their main priority, although they had little power within the hierarchy of the LO. Some organizations were also completely independent from the traditional labour movement, for example, the Danish Women’s Society (Dansk Kvindesamfund), which has been an important force for equal pay in Denmark historically.

The road to ratification

Given the imprecise wording of the Convention, there were mixed opinions on how it was to be ratified. Norway and Denmark took the view – at least initially – that the Convention did not require parliament to pass an actual law, whereas Sweden thought a law was likely to be necessary. In fact, it was Norway that became the first Scandinavian country to ratify the ILO Equal Remediation Convention in 1959 (after Iceland in 1958), and Denmark followed suit in 1960. Sweden initially took the view that they did not want to interfere with the Nordic model of wage bargaining, but there was mounting pressure to pass legislation in the wake of the other Nordic countries doing so. In the end, the social partners in Sweden agreed to remove the gendered wage disparity of their own accord in 1960 as they predicted that the government would take action sooner rather than later – which they did, choosing to ratify the Convention in 1962.

Removing the gendered wage system in the private sector could not happen instantaneously, however, and in both Norway and Sweden, it was decided that it would be replaced with gender-neutral pay rates over the course of five years. It was the beginning of heated discussions that continue today: How do we objectively measure work of equal value? For the purposes of this article, it is suffice to say that the three Scandinavian countries initially took different approaches. In Norway and Denmark, neutral job evaluations would rank occupations based on their value were attempted with very mixed results. Despite requests from Swedish women, Sweden was to remove the gendered wages without any new job evaluations. Throughout these attempts, many women feared that women-dominated occupations would continue to be ranked of lower value – and therefore attract a lower wage – than men's. So, while the attempts to try to accurately implement the Convention must be lauded, historian Yvonne Hirdman has, for example, claimed that the Swedish arrangement generated little enthusiasm among women at the time.

The Norwegian LOs Kvinnenemnd was happy with the parliament’s decision to ratify the ILO Convention on equal pay. Nevertheless, in 1959 the Kvinnenemnd published a brochure written by the member and social economist, Bergliot Lie, which stated that the ratification did not solve equal pay by itself. In 1961, the Kvinnenemnd suggested that LO and NAF were to use additional methods to establish gender-neutral salaries alongside neutral job evaluations.This was to make sure that women-dominated professions were rated fairly compared to the men-dominated manufacturing occupations.

The persisting gender pay gap

The Scandinavian countries’ ratification of the ILO convention was a huge step towards equal pay as the practice of operating with openly gendered wages was abolished. Importantly, the ratification led to a continued debate and awareness about wage fairness and discrimination. However, in 1967, when the gendered wages were finally removed in both Norway and Swede - and in Denmark in 1973, it became clear that equal pay still had a long way to go. Old norms of undervaluing both women’s work and work associated with femininity remained. While each of the three countries tried to resist passing legislation out of respect for the Nordic labour model, they all ended up passing national laws to try to deal with these issues (for example, Denmark passed the newly established EU directive in 1976, and Norway passed a national equality law in 1979, while Sweden followed in 1980).

In fact, the Scandinavian countries still struggle with a gender pay gap, which varies from 11.2 percent in Sweden to 13.9 in Denmark, according to Eurostat statistics from 2021. The EU average is 13 percent. Both in the EU and in the Nordic countries, the gender pay gap has remained relatively static over the last few decades – that is, there has been little concrete progress in this area of late. A large part of the Scandinavian pay gap is due to the gender segregated labour market. But even in the standard weighted statistics on wages and salaries, where corrections have been made for factors that affect pay such as occupation, industry, education and age, gender-based, pay differences persist. In recent years, particularly the traditional female-dominated professions in the public sector have made a claim for equal pay with the argument that their wage level is too low in relation to their responsibility and education level. So, while today we may consider the differentiated wages that existed in the 1950s and 1960s horribly old-fashioned, equal pay and the issues women’s organisations, the social partners and governments were dealing with back then remain to this day.

Looking at the past can shed light on today.

This article was published in response to readers' interest in equal pay.

Further reading:

- Cathrine Holst, Hege Skjeie, and Mari Teigen, Europeisering av nordisk likestillingspolitikk [Europeanisation of Nordic gender equality policy] (Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk, 2019).

- Inger Bjørnhaug, 'Likelønn mellom marked, klasse og kjønn – LO, kvinnene og likelønna 1935–1970' [Equal pay across market, class and gender - LO, women and equal pay 1935-1970], Tidsskrift for kjønnsforskning 34, 2 (2010), pp. 109–127.

- Lena Svenaeus, Konsten att upprätthålla löneskillnader mellan kvinnor och män En rättssociologisk studie av regler i lag och avtal om lika lön [The art of maintaining pay inequalities between women and men: A legal-sociological study of legal and negotiated regulations on equal pay] (Lund: Lund University, 2017).

- Victoria Ciobanu Austveg, Verdensmestre på likestilling uten likelønn - En sammenligning av norsk og svensk likelønnspolitikk og -debatt fra 1950 frem til 2002 [World champions in gender equality without equal pay - A comparison of Norwegian and Swedish equal pay policy and debate from 1950 to 2002] (Oslo: Master thesis at University of Oslo, 2023).

Links:

- Dansk Kvindesamfund [Danish Women's Society]

- Article on ILO and Equal Pay on norgeshistorie.no

- Institute for Social Research

- International Council of Women (ICW)

- Norsk Kvinnesaksforening [Norwegian Association for Women's Rights]

- UN Women (international organisation for gender equality)