Scandinavianism in the 19th Century

Historical pan-nationalism in the Nordic region sowed the seed for cross-border cooperation.

Summary: The aim of 19th century Scandinavianism was to create closer links between the peoples of mainly Denmark, Sweden and Norway. Opinions about the pan-national movement differed not only between each of these countries, but also within them. Although Scandinavianism had very mixed fortunes throughout the 19th century and has suffered a reputation for being unrealistic, its development should not be overlooked: Scandinavianism has contributed significantly to the construction of the Nordic region as a mental notion.

The rise of nationalism and pan-nationalism in the 19th century

Pan-national ideas in the Nordic region began to blossom in the 1840s at a time when national and pan-national movements were on the rise outside the Nordic region as well. Efforts were being made to unify German- and Italian-speaking peoples, and pan-Slavism too was based on mobilization grounded in a common language or family of languages. Importantly, supporters of these pan-national movements argued that they had to attain a sufficient size to be able to assert themselves against external threats. Culture and politics were closely linked in Scandinavianism, as in most other (pan-) national movements of the time, and each of these strands must be understood in the historical context; it was possible that cultural cooperation could lay the foundation for a political association in the long term.

From the very beginning, the political vision of Scandinavianism has encompassed a number of different viewpoints. For the mainly Danish and Swedish supporters of the mid-19th century, it centred around a union of Scandinavian nations – a confederation of sorts – or a military alliance at the very least. A 'Kingdom of Scandinavia' never materialized, of course, and this is one of the reasons why Scandinavianism as a phenomenon is relatively unknown, while the nation-state narratives remain strong. However, failing to acknowledge the importance of Scandinavianism in the 19th century – as both a political and cultural movement – means overlooking important currents in both national and Nordic history.

‘Scandinavia’ today usually refers to Denmark, Norway and Sweden, but some still mean it to include the two other Nordic countries, Finland and Iceland. Scandinavianist, and later Nordic visions have varied over time and context, but it can be said that they largely applied first to the three Scandinavian countries from 1840 to the end of the 19th century, and from then on expanded to include Finland and Iceland.

Changing borders as fertile ground for new thinking

Prior to the early 19th century, the Scandinavian realms of Denmark-Norway and Sweden (with Finland) had either very little contact or were at war. In the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, the map of the Nordic region had to be redrawn because the two kingdoms – which had often been at odds with each other – were dissolved. Firstly, in 1809, Sweden lost Finland to Russia. Finland was no longer part of Sweden after 600 years. This saw the beginning of Finland as a state and a nation, with at least some national autonomy as a Russian Grand Duchy. Secondly, in 1814, the Danish King lost Norway to the Swedish King, and Norway was no longer part of the Danish composite state after 434 years. Following Swedish pressure and aggression and great power politics, the Danish-Norwegian union was dissolved. Norway was forced to enter into a personal union with Sweden, but with its own constitution and a large degree of autonomy.

Denmark and Sweden had thus been greatly reduced, and Norway, and to some extent Finland, had become countries more or less in their own right. This altered the structure of the Nordic region and laid the foundation for the gradual growth of a Scandinavian approach and greater cooperation – and to Scandinavianism.

The path from adversaries to friends

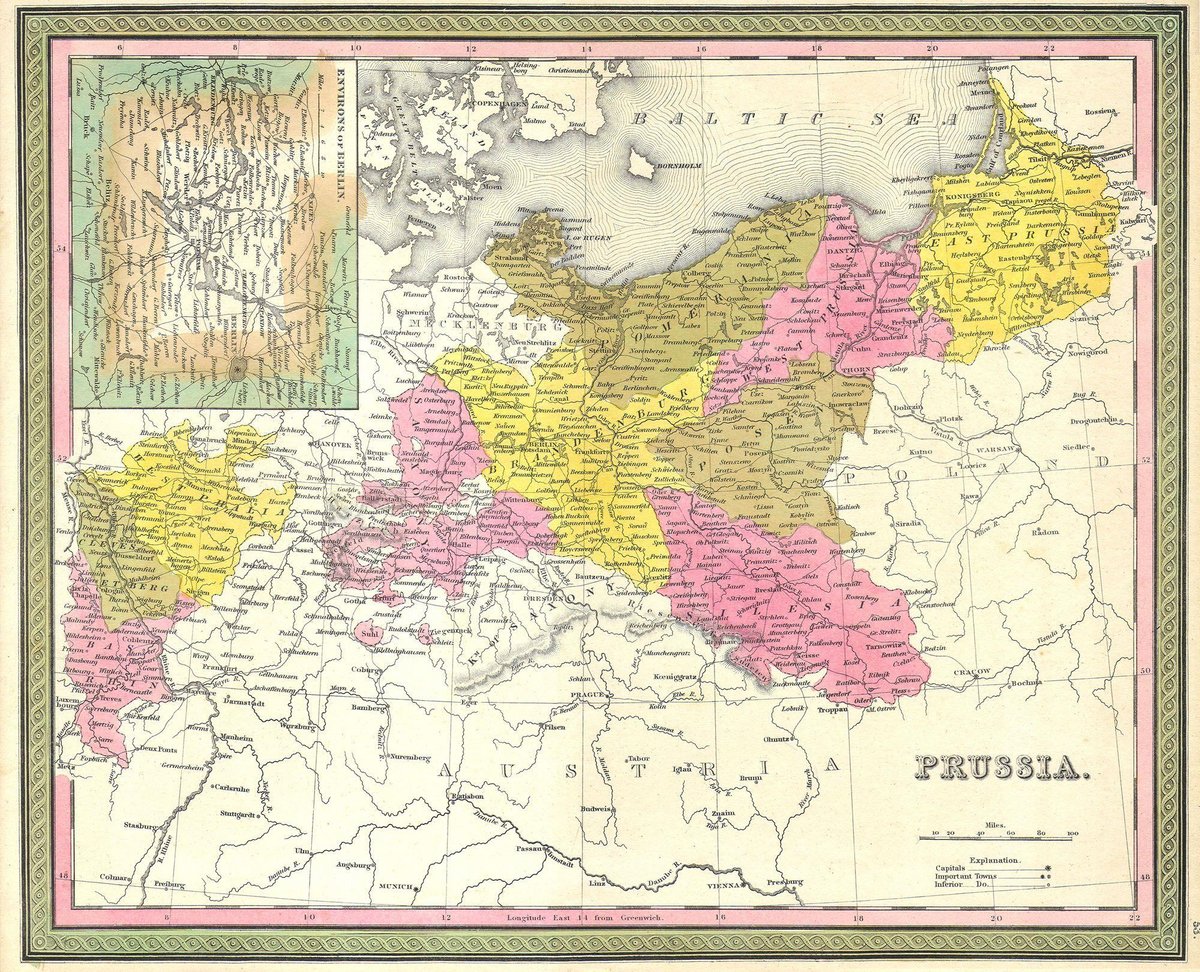

Supporters of Scandinavianism sought to emphasise the importance of brotherhood between the countries instead of the earlier adversarial relationships. But developments external to the Nordic countries were equally – if not more important – than internal ones. Principally, the development and possible threat from Prussia and Russia was decisive for relations between the Scandinavian countries, and there is no doubt that external pressure contributed to internal collaboration. Small states had to band together to survive in a world of great powers, many argued, although the threat was not felt as acutely in Norway.

Young countries finding their feet

After 1814, Norway was still a young country and it continued to have an uneasy relationship with both Denmark, which continued to be culturally dominant, as well as with the far more established Sweden, which Norway was now in union with. This naturally dampened support for cooperation with these two countries and Scandinavianism in Norway. Norway was also busy building its own nation, and did not welcome new external ties. Nor did Scandinavianism play a major role in Finland, for related reasons as well as due to Russian restrictions, although some Scandinavian activists certainly had a Finnish background.

Scandinavianism a more natural step for Denmark and Sweden

For Sweden and Denmark, Scandinavianism could more easily be seen as an extension of their own national projects. Carl Johan, who was the Swedish-Norwegian king from 1818 until his death in 1844, maintained the policy and borders from 1814, with the Scandinavian Peninsula considered a 'natural' unit. The broader Scandinavian ideas of the 1840s, however, found some resonance in Swedish anti-Russian, liberal circles. Seen from both a Danish and a Swedish perspective, the image of the external enemy certainly had a mobilizing effect.

With Oscar I, and not least with Karl XV from 1859, the idea of a Scandinavian union found its way into the Swedish-Norwegian royal ranks. This was partly because of the Swedish desire for reunification with Finland, and partly because of the possibility of expanding the Norwegian-Swedish union into a common Scandinavian union. Karl XV went to great lengths to promise military support to Denmark prior to the Second Schleswig War in 1864. However, the majority in the Swedish and Norwegian governments were more reticent about this type of Scandinavian political project, particularly if they did not receive support from other great powers. In fact, the developments in Denmark and the complicated Schleswig issue deeply challenged the continuation of Scandinavianism.

Scandinavian brotherhood put to the test

In Denmark, Scandinavianism began as both a national and liberal movement in what was still an absolute monarchy (until 1848/9). The politicization of the movement was closely linked to the growing conflict in and about the Danish-German borderland. Historically, the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein in the south of the country had a looser connection to the Danish Kingdom. While Holstein (and from 1815 Lauenburg) was German and part of the German Confederation from 1815, Schleswig was an old Danish fiefdom, with a Danish-speaking population in its northern part, but with an increasing degree of German language influence. Different languages and affiliations had not been a decisive problem in a Europe without clearly defined nation states, but, as the nation state became increasingly important, the chance of conflict along these lines grew.

The dispute regarding these territories escalated from 1842 and ultimately led to two wars between Denmark and Prussia in 1848 to 1851, and in 1864. The hope that Denmark’s Nordic neighbours would come to their aid was not realised, with only a handful of volunteer soldiers signing up for service – around 400 in the First and a slightly greater number in the Second Schleswig War. When Denmark lost the war and all the territories of the Duchies in 1864, Scandinavianism was in general declared “dead and buried”.

Scandinavian currents quietly persist

In fact, Scandinavianism was not dead and buried, and ideas of cooperation lived on and grew through an increased focus on cultural, practical and professional cooperation and transnational contacts between a variety of professions, scholars and others. It was found that Scandinavianism could actually complement the growing national focus, rather than compete with it. The vision of closer ties was based on the common Nordic, not least Old Norse, history, similar languages and cultural community – and it was on this foundation that Scandinavianism was built and it even enjoyed a quiet, and more practically-oriented renaissance after 1864/1870.

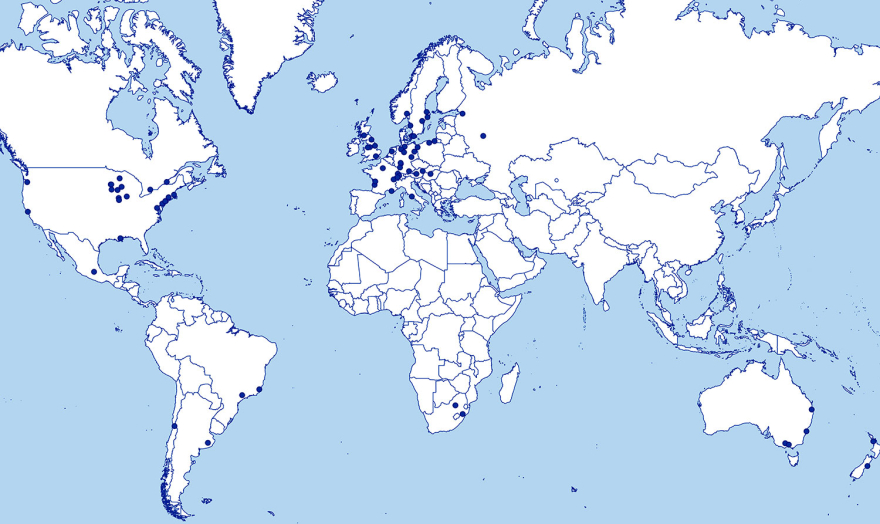

Early examples of cross-border networks

There is no doubt that transnational associations, meetings, cooperation and networks became important to the development of Nordic civil society across national borders in the 19th century. This is despite the fact that not all of these purported to be ‘Scandinavianist’, nor did they consistently have representatives from Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland (and Iceland). Examples of cross-border networks included:

- Meetings of natural scientists from across Scandinavia started in 1839.

- The first major Scandinavian student meeting took place in 1843.

- From the 1850s and 60s, national economic meetings as well as those between, for example, the clergy, missionaries and book sellers.

- Scandinavian associations abroad were also formed, such as the oldest still-functioning association is in Rome, which started in 1860.

- Cross-border civil society cooperation really took off after 1870 with, for example, meetings of jurists, teachers and a whole series of other meetings and common Nordic associations, also as part of the emerging Nordic labour movement.

Neo-Scandinavianism followed by a “Nordic ice age”

At the end of the 19th century, Scandinavianism enjoyed renewed support in the face of external threats and internal conflict. These included reports of the German power using force against the Danish population in Schleswig, the increasing Russification of Finland, and increased tensions in the personal union between Norway and Sweden. Finland became more important in the Scandinavist constellation, and there was clearer Nordic – rather than Scandinavian – rhetoric, with increasing reference to the Nordic region and Nordic associations.

In 1905, however, Norway unilaterally pulled out of its personal union with Sweden and sent Nordic cooperation into crisis. This led to a “Nordic winter”, and meetings of all sorts were cancelled, boycotted or postponed and associations dissolved. Nordic cooperation became once again politicized and Scandinavianism became discredited, particularly in Sweden.

The First World War revitalised Nordic cooperation once again, and resulted in closer cooperation, eventually involving broad parts of the societies. The ambiguous 19th century project of Scandinavianism was succeeded by a culturally and practically oriented Nordism, strictly based on respect of each Nordic country’s sovereignty.

History puts today's events into perspective.

This article was published in response to readers' interest in the joint history of Norden.

Further reading:

- Ruth Hemstad, “Skandinavisme og skandinavisk samarbeid”, norgeshistorie.no.

- Ruth Hemstad and Peter Stadius, eds., Nordic Experiences in Pan-nationalisms: A Reappraisal and Comparison, 1840-1940 (London, Routledge, 2023).

- Rasmus Glenthøj and Morten Nordhagen Ottosen, Scandinavia after Napoleon. The Genesis of Scandinavianism (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2024).

- Rasmus Glenthøj and Morten Nordhagen Ottosen, Scandinavia and Bismarck. The Zenith of Scandinavianism (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2024).

- Tim van Gerven, Scandinavism: Overlapping and Competing Identities in the Nordic World, 1770-1919 (Leiden: Brill, 2022).