The Nordic Countries during the Cold War

Further attempts at greater Scandinavian unity on defence fail and the Nordic countries turn towards other European and international partners.

Summary: The Nordic countries developed very differently during the Cold War. This was partly due to their varying experiences during - and different geopolitical positions coming out of - the Second World War. However, they were often seen as a "third way" between communism and capitalism, and even nurtured this perspective, which was edged with Nordic exceptionalism. Overall, the dominance of social democracy at home and the need for these small states to form international and European alliances meant that the Nordic countries did in fact embody a middle way of sorts - albeit each from their different geopolitical and security positions.

The Nordic Countries at the start of the Cold War

The Second World War completely changed the picture of security policy in Europe. On the one hand, the Nordic countries emerged from the war with very different experiences and relations to the outside world. On the other, the geopolitical picture had completely changed. It was precisely the Nordic countries' different experiences of the Second World War and their disparate relations to the outside world at its end, that led to very uneven developments and positions during the Cold War.

The Nordic Region and the "Third Way"

During the Cold War, the Nordic countries branded themselves, and to varying degrees perceived themselves as, a "third way" between communism and capitalism. Despite roots going further back in time, the idea of a "third way" or a "middle way" really became popular in the 1950s. This was partly due to the Cold War's bipolar division between communism and capitalism, and partly to the rise and expansion of the welfare state. The Nordic countries may have been capitalist and democratic, but the social democratic welfare models, with significant state control and regulation of the economy, were nevertheless a "softer" version of capitalism than, for example, the American insistence on the free market. Although the third way was not always entirely understandable to Denmark and Norway's partners in NATO, it could nevertheless be used for propaganda purposes to demonstrate that in the West, unlike the East, there was room for political variation.

The self-perception of "a third way" did not only apply in socio-economic terms. It was just as much a political-ideological project to stand apart from, or rather be above, the dirty realpolitik conflicts of the great powers. The Nordic countries were small states, but they were (they believed) great moral powers. Here, a certain element of Nordic exceptionalism can be seen, which was grounded in the idea of a common past, moral superiority, and a unique opportunity (and thus obligation) to resolve differences peacefully.

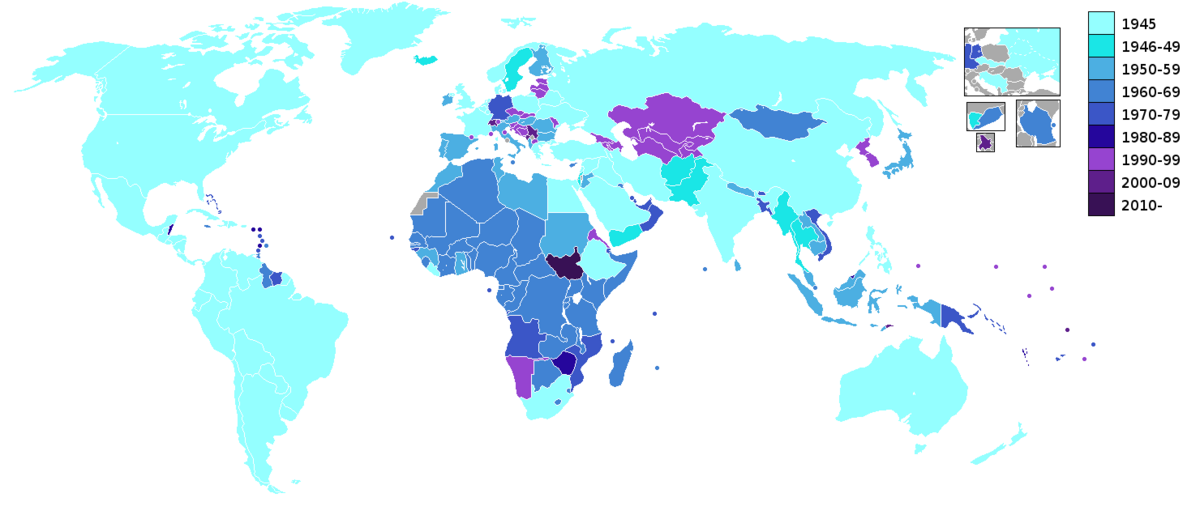

Timeline of when states joined NATO

- 1949 Belgium, Canada, Denmark, USA, UK, France, the Netherlands, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, Norway, Portugal

- 1952 Greece, Turkey

- 1955 Germany

- 1982 Spain

- 1999 Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary

- 2004 Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia

- 2009 Albania, Croatia

- 2017 Montenegro

- 2020 North Macedonia

- 2023 Finland

- 2024 Sweden

Small state diplomacy

As small states, the Nordic countries' foreign and security policy objectives were to strengthen an international order based on diplomacy and international law, in order to reduce the risk of larger and more powerful actors abusing their position to browbeat smaller ones. It was for this reason that the Nordic countries were such staunch supporters of the UN and they were to be found in several of the UN's peacekeeping missions. This commitment was an extension of Nordic normative values and ideals of internationalism, peace and reconciliation, and enabled the Nordic countries to act as bridge builders and solvers of conflict. At the same time, it was a way of working towards a more secure and stable world order by preventing local conflicts from escalating into a confrontation between the superpowers, which could also drag the Nordic countries into war. Additionally, it could not distablise the "Nordic balance" because the UN was the recognised actor.

In Sweden, the UN missions also served a purpose within the domestic policy arena as a response to criticism of its neutrality, while for Norway and Denmark it was a way to demonstrate to the outside world (and especially the Soviet Union) that, despite their NATO membership, they were peace-loving states that posed no threat to anyone. The Nordic countries took part in peacekeeping missions in, for example, Egypt in the 1950s-70s, Cyprus in the 1960s and 1970s, and Lebanon in the 1980s. These missions were considered very successful and were to form the backbone of Nordic defence co-operation after the Cold War.

The Nordic countries also increasingly positioned themselves as pioneers in relation to international solidarity between the Global South and the Global North. Norway, for example, was the second country in the world without colonies to provide bilateral aid, and for Finland these issues became pertinent after the country became a member of the UN in 1955. While Danish and Norwegian policy on decolonisation issues in the 1950s had taken into account NATO allies such as France and Britain, in the 1960s, attitudes shifted – in line with the other Nordic countries – and the two countries expressed more obvious support for those countries demanding independence, even if it was contrary to the wishes of the alliance’s partners. For example, the Danish Social Democratic government supported the Marxist rebel movement MPLA in Angola in the 1970s, while the United States supported a competing organisation.

The most prominent Nordic voice in the North-South debate was the Swedish Social Democratic Prime Minister Oluf Palme (1927-1986). Palme became world-renowned as a champion of oppressed peoples and social justice. He was a fierce critic of the apartheid regime in South Africa and the American involvement in the Vietnam War, and he supported independence movements regardless of political affiliation in Central America, Asia and Africa. However, he was also denounced for not criticising human rights violations in the communist regimes in Eastern and Central Europe.

The Nordic Region and European integration

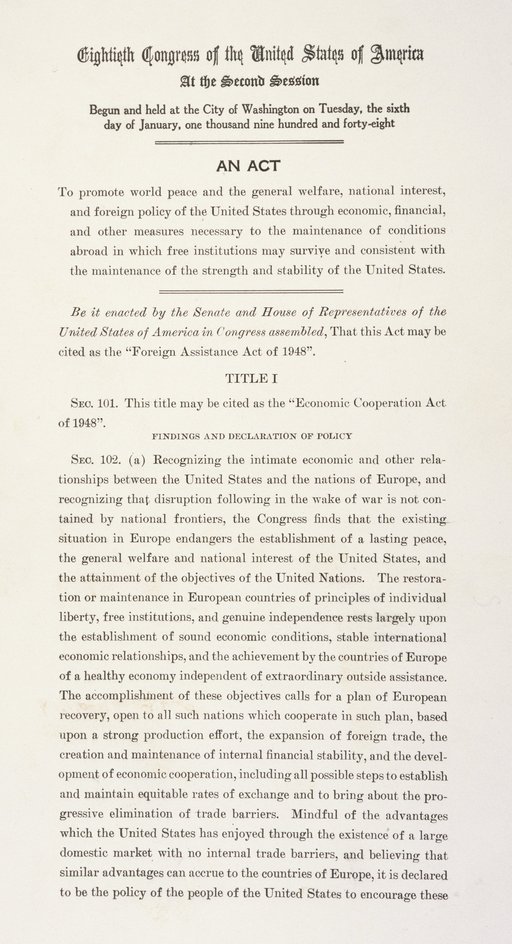

Against the background of the nascent East-West dispute in the late 1940s, it was considered vital by American decision-makers that Western Europe was economically and politically stabilised as well as being firmly anchored in a democratic capitalist bloc. This was one of the reasons why the United States offered Europe financial aid in the form of the Marshall Plan, which all the Nordic countries accepted except Finland. Economic integration was a requirement attached to receiving aid under the Marshall Plan, and this was achieved through the establishment of the Organisation for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC), which was to handle and coordinate the reception and use of the Marshall programme, and which made it impossible for Finland to participate given its relationship with the Soviet Union. Norway and Sweden initially tried to get the UN's economic organisation to coordinate the relief response in order to reduce U.S. influence and, in so doing, avoid an approach that fostered the formation of geopolitical blocs which was inherent in the Marshall Plan.

However, the Nordic countries were not keen on European integration during the early period of the Cold War and only half-heartedly committed themselves to The Congress of Europe at the Hague in 1948. Denmark, Norway and Sweden may have been founding members of the Council of Europe in 1949, but, together with Great Britain, they opposed the federal and supranational aspects proposed by other countries.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, however, other Western European countries steered towards stronger supranational integration, strongly encouraged by the United States which was also involved in the plans. For the Americans, but also West German decision-makers, it was crucial from a Cold War perspective that West Germany was closely linked to Western Europe in order to make a future with a united but neutral Germany impossible (a scenario that was favoured by the Soviet Union). France would have preferred to be without a rebuilt and strong West Germany, but it had to bow to pressure, partly because it was dependent on American support to wage its colonial wars in Indochina, and partly because the Cold War made it difficult to cooperate with Moscow on the question of Germany's future. The solution for the French was to bind Germany via European integration with strong supranational institutions. It is in this light that the initiatives for European integration during the Cold War must be viewed, an integration process which also gradually started to include the Nordic countries.

The Nordic Region and European market formation

In 1952, the "Six" (Benelux (consisting of Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands), France, Italy and West Germany) set up the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) with the aim of minimising the risk of a new military build-up by making coal and steel production a common concern. Five years later, the areas of cooperation between the six countries were extended, again encouraged by the United States, when the adoption of the Treaty of Rome in 1957 led to the creation of the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom) and the European Economic Community (EEC).

Sceptical about these trends, Britain launched a counterproposal for a larger but less binding free trade area within the OEEC framework. Together with Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, Austria and Portugal, the British established this community, the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) in 1960 as a counterweight to the "Six". For both Britain and Denmark, however, the EFTA was only the next best solution (in the case of Denmark because agricultural products were not part of the free trade area), and both countries applied for admission into the EEC as early as 1961. Norway followed in 1962. However, President de Gaulle rejected the British application prompting Denmark and Norway to withdraw their applications. This was repeated in 1967, reducing the likelihood of any rapprochement between the Nordic countries and Europe.

Nordic attempt at a common market

This, in turn, was the catalyst for yet another Nordic integration initiative similar to the Scandinavian defence negotiations: an attempt to form a Nordic common market, known as Nordek. For Danish governments, the rationale was to use Nordek as a platform for a more independent Nordic rapprochement with the EEC without making it dependent on British membership. This ambition was at that point in time tricky for Finland because of its powerful neighbour. Despite conflicting views, Nordek negotiations continued, and in 1970 a treaty was made ready for signature. However, the Soviet Union made it clear that a Nordek with close ties to the EEC was unacceptable, and when Finland jumped ship, the whole project fell apart.

The resignation of President de Gaulle in 1969 meant that the path towards community membership was again clear. Denmark and Norway reapplied, but approval by referendum was required as a first step in both countries. While a majority of 53.3% of Norwegians voted no in 1972, the 63.3% majority vote of the Danes paved the way to them joining the EEC. The attraction of the enlarged EEC had now become so great that the remaining Nordic countries also entered into free trade agreements with the EEC, even Iceland which had joined EFTA in 1970. While European cooperation came to a virtual standstill in the early 1980s (there was talk of Eurosclerosis), a renewed dynamism started with the Single European Act of 1986, and the Maastricht Treaty of 1992 which laid the foundations for the European Union (EU), including the Economic and Monetary Union which underpins the euro. With the formation of the EU, the EEC was transformed into the European Community (EC), one of the EU's three pillars (the others being Common Security and Defence Policy, and Justice and Home Affairs).

The end of the Cold War

The end of the Cold War allowed neutral countries such as Sweden and Finland to consider EU membership. In the early 1990s, they applied for admission, as did Norway. In 1994, however, the Norwegians again voted against membership of the EU. On the other hand, Sweden and Finland became members in 1995, although in Sweden, it was with only a slim majority and after intense debate.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, countries in the former Eastern bloc were also given the opportunity to apply for admission to the EU. They did so in order to consolidate their newly established democratic systems and to gain access to the internal market. The application for EU membership has often been seen in parallel to also achieving NATO membership, in a bid to strengthen their position when it comes to security policy.

Putting a spotlight on previous conflicts helps to illuminate today's security situation.

This article is published in response to readers' interest in historic wars in Europe, particularly since the invasion of Ukraine.

Further reading:

-

Helge Pharo, ‘Scandinavia’. In ed., D. Reynolds, The Origins of the Cold War in Europe. International Perspectives (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994).

-

N. Ludlow, 'European integration and the Cold War', In eds., M. Leffler & O.A. Westad, The Cambridge History of the Cold War (2010) pp. 179 - 197.

-

Thorsten B. Olesen, ed., Interdependence Versus Integration. Denmark, Scandinavia and Western Europe, 1945–1960 (Odense University Press, 1995).

-

Thorsten B. Olesen, Norden i FN 1956–1965. (The Jean Monnet Centre Aarhus University, 2003).

-

Thorsten B. Olesen, ‘Choosing or Refuting Europe. The Nordic Countries and European Integration, 1945–2000’, Scandinavian Journal of History 25, 1–2 (2000) pp. 147–168.