Photography, Settler Colonialism and Research in the Arctic

New ways of using photography in and outside research can help decolonisation in Svalbard and beyond.

Summary: Historically, photography has played a large role in creating certain images of the Arctic - images that are usually associated with settler colonialism. However, new and important approaches seek to decolonise photography as a method. Photography is relevant in research of the Arctic, including as a way of documenting something or as part of the research process itself. Communities are becoming increasingly aware of the impacts of research and in many places they insist on “nothing about us without us.”

Images and photography as part of the settler-colonial heritage in the Arctic

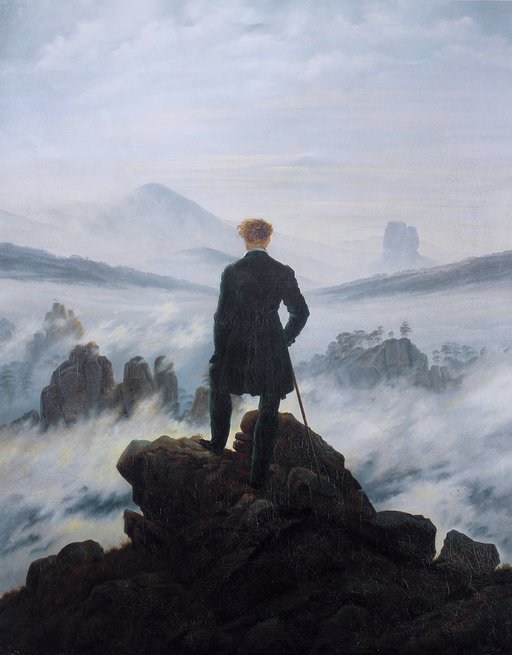

Prior to photography, Western images of the Arctic often came from voyages of exploration in the 16th to 18th centuries. These images depicted the region as barren and timeless. Combined with Europe’s colonial mindset, this projected view of the region meant it was seen as available for exploitation, be it in the form of whaling, trapping or, later, mining. The 19th century saw an increasing interest in travel and the desire, in the Western world, to experience the sublime in nature. A well-known depiction of this kind of experience is 'The Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog' by the German painter Caspar David Friedrich from 1817, which you can see here. Christopher P. Heuer’s book from 2019 Into the White: The Renaissance Arctic and the End of the Image gives a good historical overview of the varying depictions of the Arctic.

Photography as we think of it today can be traced back to the 19th century, emerging at about the same time as this ‘Heroic Age' of Polar Exploration by Europeans and people of European descent began. As photography developed, it also became a way to document (or perhaps we should say ‘portray’) these voyages, including the increasingly feverish race to the North Pole. In the popular culture of the 19th century, polar explorers were seen as heroes. Illustrated and sensationalized accounts of their voyages helped perpetuate the image of a colonizing people as ‘conquerors.’ Just as in Friedrich’s image, a single, male, ‘hero’ was often at the center of the photograph. All the others who made the trip possible, including many Indigenous men and women, were left out of the frame of the image.

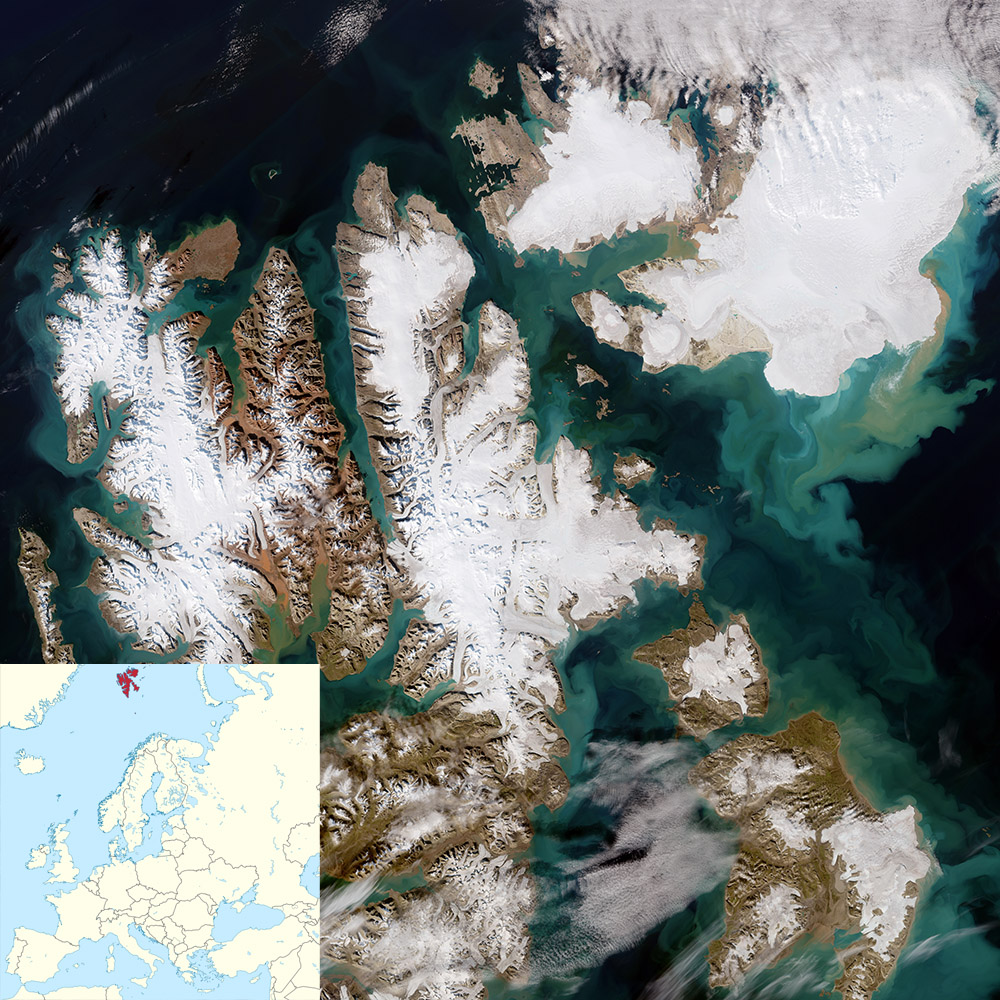

Settler colonialism refers to settlers who colonize areas where they 'copy' the life they lived at home. Examples include New England, Australia, and New Zealand, in relation to British colonialism, and the Faroe Islands, Iceland and Greenland, in relation to Norway in the Middle Ages. There are many different types of colonialism. For example, Jürgen Osterhammel, Colonialism. A Theoretical overview from 1997 (originally in German) suggests six major forms.

This selective, colonial, gaze was common in the 19th century, whether turned towards the landscape or the people inhabiting it. As Jarrod Hore explains in Visions of Nature, landscapes were often shown as idyllic and uninhabited. People were rarely shown in their natural environment. Instead they are presented in a studio, apart from the land - oddly deterritorialized. These images, and the way they were framed, helped to shape how people of European descent colonized other lands, economically and culturally. Arguably, what they record and ‘document’ has more to do with the euro-modern perspective than that of the people living in the Arctic or in the other regions being ‘explored.’

Photography and research

All kinds of research are conducted in the Arctic today, in both the natural and the social sciences. Often photos, and increasingly videos and drone imagery, are used as snapshots of the current state of the place being researched, or to communicate the outcomes of a particular project. For example, photos are commonly used in presentations in order to illustrate an issue or a finding. Here, photography is not an intrinsic part of the research but rather a way of communicating or explaining the work.

Connected to this, but differing from it, is how photography can be used as a way of documenting a research subject, including what has occurred, or has been produced. In this case, photography is used as a part of the research process but not as a method of inquiry. The same photos will of course also be used for communication purposes. Photography can also be used as part of an arts-based approach to doing research. For example in the social sciences, a researcher may present photos to elicit responses (photo-elicitation) or people can be asked to take photos as part of a way of understanding their point of view (photo-voice). In this example, the photos are an integral part of the research process.

Although some researchers do live in the Arctic where they conduct research, many only come for a set amount of time in order to conduct ‘fieldwork.’ Arctic communities are becoming increasingly aware of the impacts of research and in many places they insist on “nothing about us without us.” Good resources for learning about how to conduct research in the Arctic are the Greenlandic site ‘Arctic Hub’, the Saami Council site, and the US site ‘Respectful Research.’ Whether you are a visitor or from the place you are researching, it is important to consider how you are conducting your research and how you are taking your photographs. As the history of anthropology and ethnographic research shows, many images were used to portray an idea from outside projected onto a community.

Decolonizing research methods refers to questioning underlying conceptions of knowledge within many branches of academia and exposing these as, for example, monocultural and Eurocentric. It can therefore be very far-reaching and extend also to embedded ideas of teaching and learning generally.

Decolonizing the Arctic through photography as a research method

Photography has a long and entangled history with settler colonialism. However, as with all tools, it is possible to do photography in other ways. A helpful approach to start thinking about photography differently - including reflecting on how we view things and people through the lens - can be found in Claudia Mitchell’s book Doing Visual Research. An obvious and essential first step is obtaining prior consent when taking pictures of people or specific places (such as private homes or sacred spaces). But it is also important to examine the photos afterwards and question what is being shown - and what has been left out of the frame. It is essential to respect the community where researchers are based or visiting, and to recognise that research conducted with and for a community is not the same thing as research about a community. Respectful research can be conducted whether as a visitor or a member of the community as long as all aspects of the work are approached with care.

While living and researching in Longyearbyen, Svalbard, I took photos of the natural and built environments every day. Given that my work centered on identity of place (where the place itself is the main focus) it was important to find ways of researching that were not uniquely human-centered. My daily photography practice helped me to develop an embodied understanding of place, one linked to the specific aspects of the place itself. For example, taking photos and analyzing them afterwards helped me to develop a close attention to detail: I learned to see how the texture of sea ice is different from that of glacier ice, or how the snow compacts and changes over time. This brought a different, more grounded way of understanding place. Instead of seeing the place from the outside, I began to learn, over time, how to read the landscape and the built environment around me, and to better understand the various ways humans interacted with it.

This shift in perspective also made me question more broadly the way(s) we were doing academic research. By using the camera as a method of inquiry, the ways in which my framing was influenced by my own settler-colonial heritage became clearer. Too often research based on the Western ‘experimental method’ removes the researcher from the work, creating a view from elsewhere that is presumed to be ‘objective’. As explained above, photography has often contributed to an ‘othering’ vision of the Arctic. Reflecting on how we practice photography - including the moment of taking the photo, how we work with it after, and how we use it to present the research - provides insight into how we are framing the subject of our research. In turn, this helps us challenge our own framing and the research methods we are using – an essential aspect of trying to use photography in helping to decolonise the Arctic.

Analyzing and using photography in research can open up new perspectives.

This article is published in response to readers' interest in new methodologies and the Arctic.

Further reading:

- Christopher P. Heuer, Into the White: The Renaissance Arctic and the End of the Image (Princeton University Press, 2019)

- Claudia Mitchell, Doing Visual Research (Sage Publications, 2011)

- Gillian Rose, Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials (Sage Publications, 2023)

- Jarrod Hore, Visions of Nature: How Landscape Photography Shaped Settler Colonialism (University of California Press, 2022)