Cooperating Across Norden

Cooperating Across Norden

On this theme page, you can find articles and podcasts about Cooperating across the Nordics.

The diverse peoples and territories within the Nordic region cooperate in many different ways, but it can be loosely categorised into formal and informal cooperation.

How do the Nordics formally cooperate with one another?

There are a variety of organisations which facilitate the discussion and coordination of policies in areas of joint interest to the Nordic countries. The Nordic Council (founded in 1952) fosters co-operation among parliamentarians from member nations, and the Nordic Council of Ministers (founded in 1971) promotes cooperation among government officials. Without the power to make laws, these bodies are nevertheless influential and useful instruments for Nordic cooperation and for pursuing Nordic interests outside the region. Likewise, all the Nordic countries are members of the Arctic Council, which was formally created with the signing of the Ottawa Convention in 1996. All these fora provide opportunities for similar-minded political parties from different Nordic countries to meet and align their policies, and foster a trans-Nordic bureaucracy .

The mechanisms of formal Nordic cooperation have been much studied and even imitated. For example, the British-Irish Council follows the Nordic model. The Nordic Passport Union was established as early as 1958 and was a forerunner of the European Schengen system. However, these institutions have more recently been criticised for their limited impact. They operate slowly (often taking a year or more to deliberate issues) and the Nordic Council’s lack of legal power has limited its ability to influence and change policy. Another criticism has been that the autonomous territories of the Faroe Islands and Greenland (which are part of the Danish realm), and the Åland Islands (which are part of Finland), have not had a big enough say.

Some key issues are difficult to tackle within formal cooperation. Defence and security remained largely absent from the formal agenda of the Nordic Council as well as the Nordic Council of Ministers throughout much of the second half of the 20th century, hindered largely by the Cold War. Significant collaboration was undertaken on the ground during that time though, and since the 1990s and particularly during the last 10 years, concrete attempts have been made to formalise security cooperation in this area with mixed results.

Other types of cooperation have built up gradually in a bi- or multi-lateral way throughout the years. While key processes to do with Nordic civil security cooperation are founded by the work of the Nordic Council, there are also numerous other agreements and collaborations across borders in order to deal with disasters, accidents, crises and emergencies. Another example is the signing of the Nordic Environmental Protection Convention. A multilateral convention from 1974, it was the first international environmental treaty that implemented the polluter-pays principle for transboundary pollution.

The history of formal Nordic cooperation

Even prior to the formation of the Nordic Council in 1952, the Nordic states were widely considered to form a distinctive region by virtue of their strong historical ties. Nineteenth century Scandinavism envisaged a federal state made up of Denmark, Norway and Sweden. This idea was more or less replaced with Nordism in the 1920s, a movement which was less ardently intergrationist than Scandinavianism, but still supported the fostering of mutual understanding, respect and friendship across the Nordics.

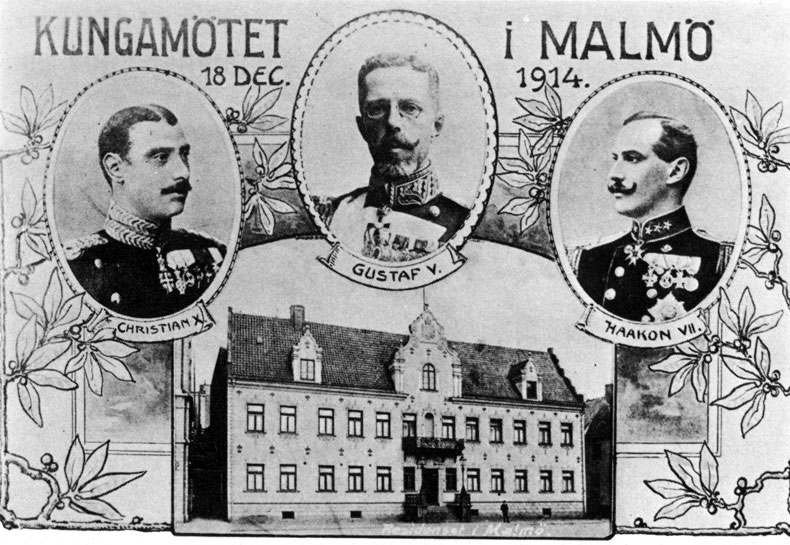

The ’Three Kings Meeting’, which took place in 1914 with the kings of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, is said to have cemented Scandinavian solidarity and cooperation, and is seen as an important precursor to more formal cooperation later on. At the time, the three countries wanted to present a united front in the face of the First World War, and to declare that they were all neutral and would not be swayed by the Great Powers. Under the surface, though, there were tensions: Each nation had divided loyalities, and Norway was a very young nation determined not to be dominated by its powerful neighbour from which it had become independent in 1905.

Although the Three Kings Meeting has been heralded as a significant one, there were of course many other cross-Nordic meetings and collaborations in the first half of the twentieth century and even before that. Examples include, after the war in the 1920s, members of the Scandinavian parliaments met annually under the auspices of the Northern Inter-Parliamentary Union, and the Nordic nations worked together to a greater or lesser extent within the League of Nations and later the United Nations; cooperation across national borders and inter-governmental co-operation certainly predated the founding of the Nordic Council in 1952.

Defence and economics: challenging areas for Nordic cooperation?

Yet the path of Nordic cooperation did not always run smooth. After the Second World War, attempts to formalise Nordic security and defence cooperation in the late 1940s floundered and were overtaken by Norway, Denmark and Iceland becoming founding members of NATO in 1949.

Immediately before and after the Nordic Council was founded in 1952, there was much debate over what form cooperation should take, primarily with respect to the economy and defence. You can get an idea of the different national agendas – and those of individual political parties even – in the articles, ’Nordic Cooperation 1947 – 1960: a Norwegian perspective’ and 'Nordic Economic Union (NORDEK): a Danish perspective'. Norway’s attempts to support a customs union/common market in 1947, 1950 and 1954 belied how it repeatedly blocked initiatives for closer cooperation; the Labour government’s pro-Nordic stance could not overcome international as well as domestic concerns.

The never-realised NORDEK plan (so called due to the Swedish name for Nordic Economic Union (NORDiskt EKonomiskt samarbete)) grew out of a Danish initiative to create a Nordic common market. The plan attracted much attention in the years from 1967 to 70. It was a serious attempt to create a comprehensive, Nordic political and economic organisation of cooperation, but disagreements that could not be resolved persisted. For example, the Danes and Finns could not agree on what sort of cooperation there should be with Europe. After many years of sluggish negotiations, plans were finally dropped when the opportunity for Denmark and Norway to join the EEC arose in 1969-70 and both countries went on to have referenda in 1972.

Today, these small, open economies are well-integrated on the international stage, thanks in part to their involvement in NATO (Denmark, Iceland, Norway), and NATO’s Partnership for Peace (Sweden). Their integration in the global economy, and the European one in particular, can be greatly attributed to the Nordic countries’ membership of the European Union, the European Free Trade Association and the European Economic Area; each of the five countries has had differing economic relationships with Europe over time, with Finland currently being the only country to have adopted the euro, and Iceland and Norway the only Nordic countries not to have become members of the EU. Modern economic moves for greater Nordic integration also include initiatives like the establishment of Nordic companies, and there are of course natural economic ties that reach across the borders of neighbouring countries, like the collaboration of the Danish and Swedish municipalities in the Oresund region, for example.

Activists and friends working together in different contexts

Cross-Nordic working has created a fertile ground for discussing national policy-making throughout much of the twentieth century as well as to this day. For example, different representatives have created a network across borders through the labour movement, and the social democratic parties, and even the communist parties and factions – as part of the Scandinavian Communist Federation in the 1920s, for example. You can read the biography of Karl-August Fagerholm, 1901-1984, an influential figure in Finnish politics during the post-war period and a good example of a politician who was a keen supporter of Nordic cooperation.

What is now known as Nordic civil society refers to the tradition for strong popular movements and voluntary organisations founded on the principles of human engagement in society, self-empowerment, and a well-functioning democracy. There are many national and cross-Nordic associations and collaborative iniatives stretching back to the nineteenth century. Friendship links between towns in different Nordic countries emerged after the Second World War and have included cooperation between schools, organizations, associations and official bodies, as well as place-marketing and branding, more recently. Much of civil society cooperation is funded by the Nordic Council of Ministers. Another association worth mentioning is the Norden Association (Foreningen Norden) which aims to:

”contribute to an active public debate, influence the decision-makers of official Nordic co-operation and take initiatives that can help to deepen Nordic co-operation internally and externally, promote free movement in the Nordic region and contact between Nordic citizens.” (Read more here: Foreningerne Nordens Forbund).

Additionally, working across national and regional borders has influenced important movements like the disability movement and the feminist movement. With the birth of the environmental movement in the 1960s and 1970s, it made particular sense for the Nordic countries to work together on complex and scientific research and decision-making which would otherwise be more costly. There has also been some cooperation on development aid, particularly in the early days of its development in the 1960s and 1970s. However, in this podcast, there is a discussion about how there has been less cooperation in this area than one might expect: Nordic Cooperation: Self-interest or Altruism?

In the university world, there has been collaborations on multiple levels, officially and unofficially, and students are permitted to study in other Nordic countries. Similarly, over a period of more than 70 years, the Nordic countries have worked together to produce comparative statistics on social and health issues with the goal of informing researchers, public officials, politicians and the public, through two committees which are still on-going: one for social welfare (NOSOSCO, established in 1946) and one on health (NOMESCO, established in 1966).

Why do people living in the Nordic countries work together?

Many reasons are given for why the Nordic peoples have a tendency to work together. Some quote joint history, cultural ties and similar languages. Others say that learning best practices from each other was important in the making the welfare states. It is also often cited that the countries are relatively small states, so they need the the support of one another. While collaboration in areas like environmentalism and development aid can give the appearance that the Nordics are altruistic internationalists, cooperation is arguably more driven by self-interest and the agenda-setting of domestic politics at any given time.

Others question whether the Nordic countries really are that similar to one another - or different from the rest of the world – and suggest that discussion of 'the Nordics' is simply a branding exercise, albeit one that is successful in facilitating cooperation. Arguably, other countries, like Estonia for instance, could be included in some of these ’Nordic’ characteristics.

NOTE: This theme page was written prior to the invasion of Ukraine.

Articles to do with the theme Cooperating Across Norden on nordics.info:

Further reading

- Franz Wendt, Cooperation in Nordic Countries: Achievements and Obstacles (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1981).

- Johan Strang and Jussi Kurunmäki, eds., Rhetorics of Nordic Democracy (Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 2010).

- J. Strang, ed., Nordic Cooperation (Routledge, London, 2016).

- M. Hilson, ’Consumer Co-operation in the Nordic Countries, c.1860-1939’ in M Hilson, S Neunsinger & G Patmore, eds, A Global History of Consumer Co-operation since 1850: Movements and Businesses. Studies in Global Social History, 28 (Brill, 2017) pp. 121-144.

- N. Gøtz, ’‘Blue-eyed angels’ at the League of Nations: the Genevese construction of Norden’ in Götz, N., & Haggrén, H. eds. (2008). Regional Cooperation and International Organizations: The Nordic Model in Transnational Alignment (1st ed. Routledge, 2008).

- Pauli Kettunen and Klaus Petersen, eds., Beyond Welfare State Models: Transnational Historical Perspectives on Social Policy (Elgar Publishing, 2011).

- Peter Stadius, 'Hundra år av nordism: Föreningarna Norden i går, i dag, i morgon' [Hundred years of Nordism: The Norden Associations yesterday, today, and tomorrow] in Meningen med föreningen : Föreningarna Norden 100 år [The meaning of the association: The Norden Association 100 år] (Föreningarna Nordens Förbund, Copenhagen; 2019) pp. 6-72.

- Ruth Hemstad, 'Scandinavian Sympathies and Nordic Unity: The Rhetoric of Scandinavianness in the Nineteenth Century'. In Marjanen, Jani; Hilson, Mary & Strang, Johan, eds., Contesting Nordicness from Scandinavianism to the Nordic Brand (De Gruyter, 2022) pp. 35–57.