Language and the Nordic Region

Language and the Nordic Region

National languages in the Nordic countries

Danish, Finnish, Icelandic, Norwegian and Swedish are defined in relation to a nation state. Each of these five languages has a relatively fixed form (or forms in the case of Norwegian). Variations from the established norm(s) are classed as dialects or, where the variation has a social basis, sociolects. Each language exists under the watchful eye of a type of language ‘board’, official bodies overseeing the Nordic languages, which for the most part are state-sponsored, semi-autonomous bodies.

Finland has two official languages, Finnish and Swedish, as a result of its more than 600 years as part of the Kingdom of Sweden (until 1809). About 6% of the Finnish population are Swedish-speakers, and the autonomous region of the Åland Islands in Finland is Swedish-speaking. The two language groups exist peacefully, but their co-existence has led to some friction, which has also been a source of artistic inspiration.

The Faroe Islands are one of the three autonomous regions of the Nordics and here both Faroese and Danish are official languages. The islands have been part of the Kingdom of Denmark since before the dissolution of the common Danish-Norwegian kingdom in 1814. Faroese, like Danish, Icelandic, Norwegian and Swedish, is a descendant of Old Norse. It is the first language of virtually all islanders, and those who speak Danish as their native language tend to be immigrants from Denmark or children of them.

Sámi – and Finnish – belong to the Finno-Ugrian branch of the Uralic language family, which also includes Estonian and Hungarian as well as a number of languages of the former Soviet Union. Even though they have no state of their own, the Sámi tend to be treated as a single people and their varying forms of speech are often deemed to be dialects of ‘the Sámi language’. However, Sámi actually consists of three branches which are sufficiently different from each other to be considered separate languages as they are not mutually intelligible.

The different types of Greenlandic (Kalaallisut), on the other hand, are on the whole mutually intelligible, and are thus known as dialects. In East Greenlandic, many common words are replaced with near-synonyms and it may therefore be difficult for other Greenlanders. Although Greenlandic is often split into East, North and West Greenlandic, there is further variation within these geographically delineated areas. Greenlandic is a branch of Eskimoic, part of the Eskimo-Aleutic family spoken in Alaska, North Canada, eastern Siberia and the Aleutian islands. With respect to Danish, the linguistic situation in Greenland resembles that in the Faroes: Both Greenlandic and Danish are official languages, but Danish tends to be spoken as a native language chiefly by Danes, although some Greenlanders have it as their first (and sometimes only) language. You can hear more about Greenland’s language and three different researchers’ personal language experiences in our short podcast series The Nordics Uncovered: Critical Voices from Greenland.

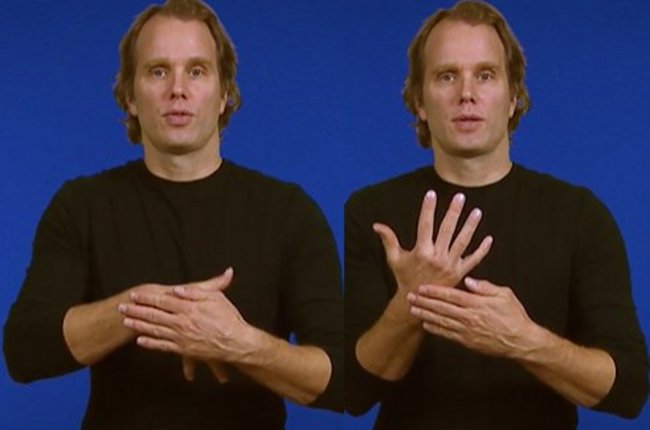

Signed languages in the Nordic countries are loosely split into a ”western” and an ”eastern” group, which reflects the fact that they arose primarily in schools for deaf children in Denmark and Sweden in the early 19th century and were later exported to the other areas. It is estimated that there are currently about 5,000 deaf speakers of Danish Sign Language, 4,000-5,000 of Finnish Sign Language, 4,000 of Norwegian Sign Language, 8,000-10,000 of Swedish Sign Language, between 200 and 300 of Icelandic Sign Language, and about 90 of Finland-Swedish Sign Language. There are additional speakers whose primary language is not a signed language, such as family members, and friends and professionals such as interpreters, social workers, teachers, and priests.

Linguistics, which is the scientific study of language form and meaning, has been a prominent academic pursuit in the Nordics since the Middle Ages, including the specialised branch of runology. Runes were a specifically Northern script, carved on stones for memorials, and on wood for everyday communication. There are some unique and interesting features of the Nordic languages which are interesting from a linguistic point of view, like the Danish ‘stød’ (glottal stop), and the Swedish double accentuation (which is why it is sometimes described that it sounds like Swedes are singing).

Is ’Scandinvanian’ a language?

The three Scandinavian languages Swedish, Norwegian and Danish are part of the North Germanic branch of the Indo-European family. From a practical point of view, ‘Scandinavian’ was – and still is – used when many Danish, Norwegian and Swedish people communicate with one another. Young people, however, increasingly resort to English in communication with other Scandinavians. Danes, Norwegians and Swedish speakers can primarily speak their own language, perhaps replacing some words, phrases, or pronouncing things slightly differently, depending on who they are talking to. At meetings of the Nordic Council and Nordic Council of Ministers, for example, and in their documentation, ‘Scandinavian’ can refer to Danish, Norwegian or Swedish, while the other Nordic languages (usually Finnish and Icelandic) are separate.

That said, mutual intelligibility – even between speakers of Danish, Norwegian and Swedish – is not straightforward, but often depends on factors like accent and dialect, among others. It also depends on the degree of exposure: Danes in Copenhagen may hear Swedish regularly, but that is not the case far from the border. Formally, the Helsinki Treaty (the founding document of Nordic cooperation) has included a provision since 1982 that Nordic schools shall include ”an appropriate measure of instruction in the languages, cultures and general social conditions of the other Nordic countries, including the Færoe Islands, Greenland and the Åland Islands.” (Article 8). This policy is not implemented everywhere, however.

Linguistic variety in the Nordic countries

There is a wide variety of other, smaller languages in the region and tracing their history can provide insight into the indigenous and non-indigenous peoples of the Nordic countries, often reflecting important political and socio-economic contexts of minority groups. Linguistic minorities have existed for centuries, such as the Finns and Sámi in Sweden, but since the 1960s particularly, minority languages have often been associated with immigration. Policies with regard to minority languages have ranged from assimilation on the one hand, where the majority language is a necessity, to multicultural pluralism on the other, where minority languages are encouraged.

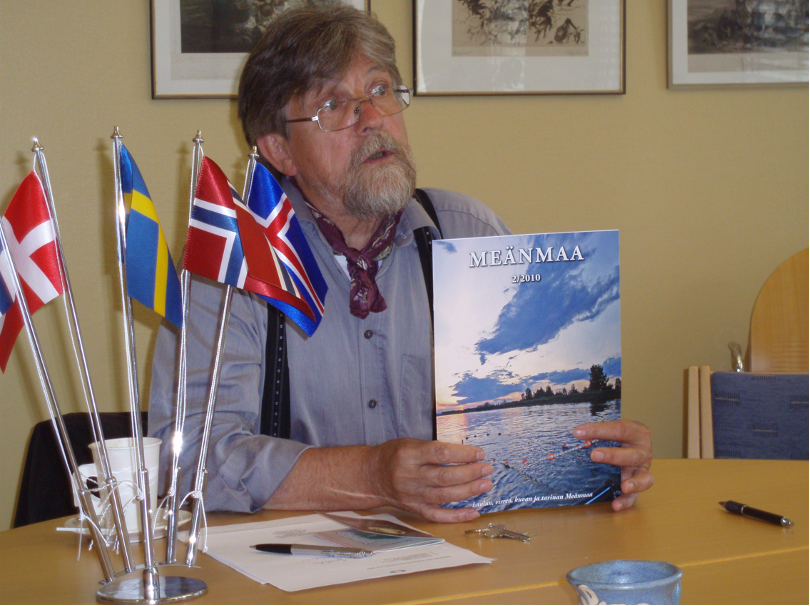

Meänkieli and Kven are two languages that both stem from Finnic varieties, that is, the Finnic branch of the Uralic language family, together with Estonian, Ingrian and Karelian. They have no language status in Finland, but are instead usually regarded as Finnish dialects However, in Sweden and Norway, Meänkieli and Kven are recognised as languages and have the status of national minority languages. Meänkieli was spoken along the shores of the Tornio and Muonio river.

In Southern Denmark, there is a German-speaking minority. The historical duchy of Schleswig, which stretched over the area where the border between the two countries is now, was divided between Germany and Denmark following two plebiscites in 1920. National minorities were left behind on both sides of the border, so a minority of people who live in southern Denmark identify as German and speak German, and a minority of German nationals south of the border identify as Danish and speak Danish. In 1955, the German and Danish governments recognised the minorities in two unilateral declarations.

Immigration has added many new community languages. The oldest of these is Romani, whose history in the Nordic countries appears to go as far back as at least the 1500s. Romani (in different varieties) is a recognised minority language in Sweden, Finland and Norway, but not in Denmark. Another minority language traditionally spoken in Scandinavia was Yiddish, but this is no longer in use today, although it remains a recognised minority language in Sweden.

It was not until the 1960s that large numbers of people speaking non-indigenous languages began to settle in Scandinavia. The long-term linguistic effect of late twentieth- and twenty-first century immigration is difficult to predict. Most probably the immigrant languages will gradually disappear locally, unless continually reinforced from the homeland, but they are likely to leave some traces in the indigenous tongues of the region; indeed such influence has already been reported. For example, ‘Rinkebysvenska’ or Rinkeby Swedish is a contemporary urban vernacular (CUV), which has developed in multi-ethnic urban areas of Sweden including a suburb of Stockholm called Rinkeby. This speech variety is mainly used by young people in addition to other languages and language varieties depending on context, and its use is reflected in rap and fiction. Similar immigrant varieties of the majority language have developed in the major cities of Denmark and Norway as well, and in other cities in Sweden.

Official policies and economic opportunities, together with cultural pressure to assimilate, can create a language shift away from heritage languages – a term which can encompass both indigenous and non-indigenous languages – towards more dominant ones. Maintaining the language and identity associated with heritage languages in the Nordic countries can therefore be challenging.

Language as identity

There has not only been societal pressure to conform and use the majority language in many of the Nordic countries, but legal measures have also been used to enforce the use of the majority language. The process of Norwegianisation, for example, is outlined in the Interview: "we won't be silenced" - Sámi language and literature, where a professor from The Arctic University of Norway discusses the Sámi language before, during and after Norwegianisation. Language is very important for identity and this has played out in some regions over a movement to maintain place names and road signs etc in particular languages.

While Meänkieli has been receding for decades, its resonance and importance remains in a common sense of identity and a shared cultural heritage. The literary work of Bengt Pohjanen, for example, a multilingual author and translator, has been important in establishing a literary and linguistic heritage for the Meänmaa region.

When priority is given to the national languages, some linguistic minorities can go unrecognised, or are even disadvantaged. Language pluralism is, as one would expect, politically contentious. However, Northern Sámi has become an official language in several municipal areas in northern Norway, and Sámi language is gaining ground elsewhere as well. Immigrant languages are often dealt with differently, partly because immigrants cannot claim indigenous status, and partly because they do not live in concentrated or monolingual areas. Most of them live in extremely diverse metropolitan areas, where 50 or more mother tongues may be present in relatively small local populations.

The Nordic languages in a global perspective

Proficiency in English is both widespread and high-level in the Nordic countries due to, amongst other things, these relatively small nations needing to be outward-looking and accessible for global trade. English remains important when communicating on a Nordic level as speaking the Scandinavian languages can exclude particularly Icelanders and Finns, although many are proficient in Swedish or Danish for historical reasons. Young people – even Scandinavians – often prefer to speak English together. But it should not be assumed that everyone is equally proficient, nor that the power of the English language goes unquestioned. Opportunities to learn and be exposed to English are, for example, linked to particular socio-economic and geographical situations, and there are legitimate concerns that English has too powerful a role.

Translation is an everyday necessity for many Nordic people who do business and exchange ideas with those outside (and to some extent inside) the region. This has led to a healthy translation industry. Often up to 60% of books published by Nordic publishers are translated texts. Membership associations and certification bodies have grown up to support translators and verify their work, and educational institutions provide relevant theoretical and practical courses. Outside the region, Nordic literature in translation remains limited, but especially the genre of Nordic crime fiction has been translated into many languages. Scandinavian films and series have also gained popularity abroad.

Ingria, now a part of Russia, was – and still is – home to Finns who settled in the region starting in the seventeenth century. Their use of the Finnish language has been politically bound up with their ethnic/national identity at certain points in history. So, while Ingrian Finns themselves have often promoted a more complex, less binary view of their identity than ‘Finnish/Not Finnish’, in 1990, President Mauno Koivisto of Finland announced that Finland would offer residence permits to Soviet citizens of Finnish descent, allowing the Ingrian Finns to ‘return’ to Finland. This policy on return migration suggested not only that Finland had a special responsibility to protect those with a Finnish identity in the Soviet Union or Russia, but also that the Finnish language was crucial in ascribing a Finnish identity to those outside of Finland. Karelian, likewise spoken in Russia, is very close to the Finnish language.

Nordic terms can be found around the world in communities of descendants of Nordic immigrants. For example, in the year 1882, 28,000 Norwegians emigrated to the USA, and from then until the 1920s, about 800,000 Norwegians emigrated to America in total. Danes and Swedes also migrated during that period. While emigration to the US is perhaps the most well-known, there have of course been other destinations. A community of Finnish migrants that moved to Argentina in 1906 founded a settlement known as Colonia Finlandesa in the province of Misiones. Finnish was lost as a language within about 50 years as a result of demographic changes related to the small number of people in the colony, return migration to Finland, the bilingualism of the founding group, and marriages with people who did not speak Finnish. Curiously, Finnish lumberjacks who emigrated to the great lakes area in North America learned the first nations language Ojibwe before they learned English, and some of their descendants are known as Findians.

Language is complex and not everything could be covered here as this text is only based on the articles we have on nordics.info to do with language and linguistics at the current time - please feel free to suggest additions!

Articles to do with the theme language and the Nordic region on nordics.info:

Further reading

- Allan Karker, et al., eds., Nordens språk (Oslo: Novus, 1997).

- E. Hovdhaugen, F. Karlsson, C. Henriksen, and B. Sigurd, The History of Linguistics in the Nordic Countries (Helsinki: Societas Scientiarum Fennica, 2000).

- Henry Minde, 'Assimilation of the Sami - Implementation and Consequences'. Aboriginal Policy Research Consortium International (APRCi). (2005).

- Lars S. Vikør, The Nordic Languages: Their Status and Interrelations (Oslo: Novus, 2002)

- Maisa Martin, ‘Multilingualism in Nordic Cooperation – A View from the Margin’, in Dangerous Multilingualism: Northern Perspectives on Order, Purity and Normality (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

- Oscar Bandle, Kurt Braunmüller, Ernst Hakon Jahr, Allan Karker, Hans-Peter Naumann, Ulf Telemann, Lennart Elmevik and Gun Widmark, ‘The Nordic Languages’ (Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 2008).

- P. Quist. P. & B. A. Svendsen, MultiLingual Urban Scandinavia. New Linguistic Practices. (Bristol: Multilingual Matters, 2010).

Links

- Lingoblog, a platform on language and linguistics (the science of language) to all with a passion for languages.

- Nordiske Språk, a website with educational material (e.g. films and quizzes) on the differences and similarlities between the Nordic languages.