Bengt Pohjanen: Creating collective memory in Meänkieli

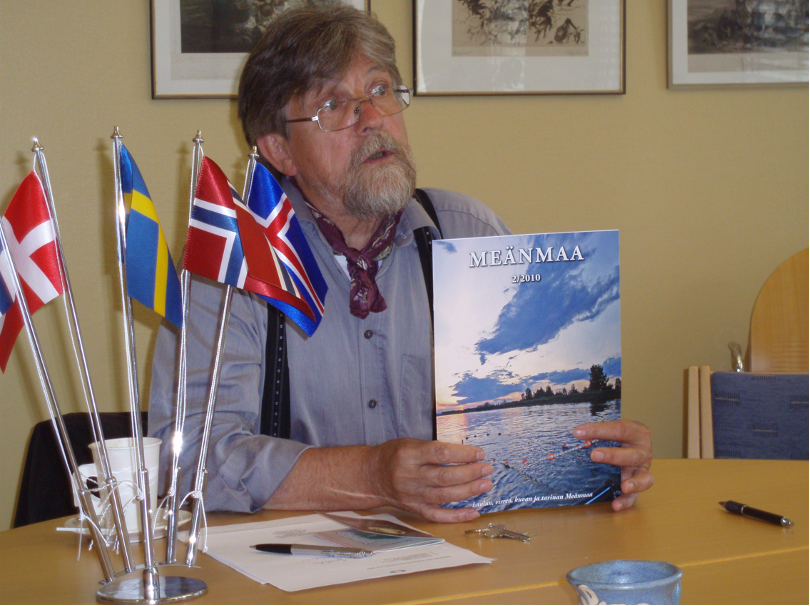

Bengt Pohjanen is a multilingual author and translator best known for his work in Meänkieli, which has been vital in establishing a literary and linguistic heritage for the population of the Torne Valley and the Meänkieli-speaking diaspora elsewhere. A central element of Pohjanen’s work is the notion that Meänmaa is more than just a geographical area, but also a virtual cultural space with an imagined Tornedalian community, their common identity and a shared Meänkieli cultural heritage.

What is Meänkieli?

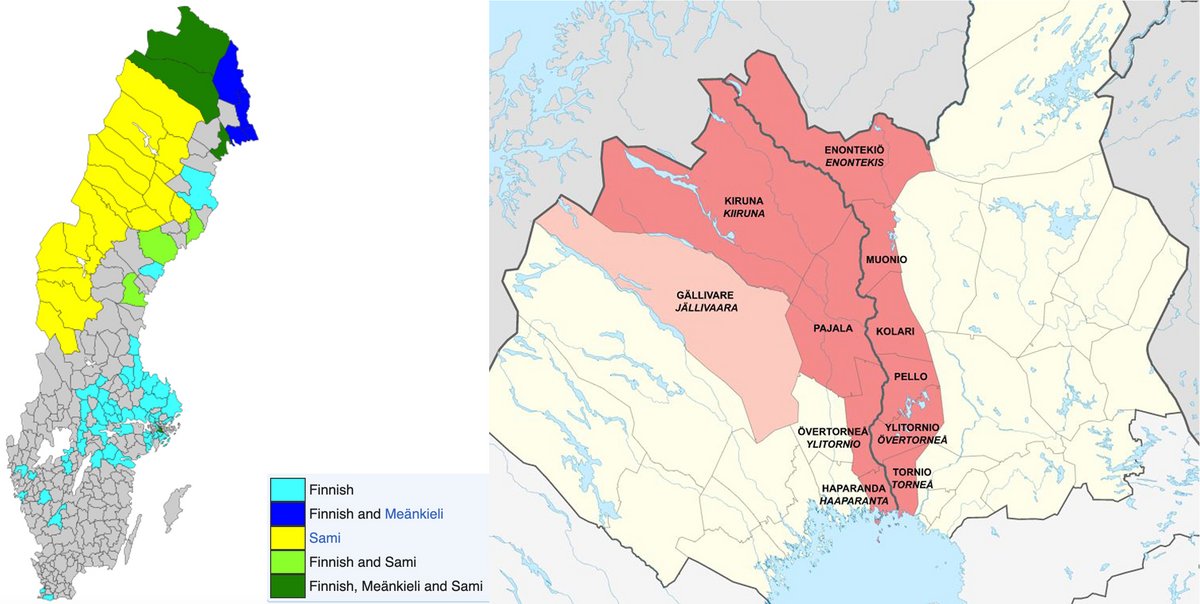

Meänkieli is one of the Baltic Finnish languages and is spoken in the Torne Valley (Tornionlaakso in Finnish and Tornedalen in Swedish). This area has been inhabited by Finns for centuries, probably since before the Middle Ages. However, there have also been other languages spoken in the area, like Sámi and Swedish. The Finnish territories were under Swedish rule between 1155 and 1809, becoming part of the Czar’s Empire after the so-called “Finland’s War” (1808–1809) between Russia and Sweden. The eastern part of the Torne Valley was annexed to Russia as the Finnish Grand Duchy, while its western part remained under Swedish rule. The Finns living on the western bank have become a linguistic and ethnic minority in Sweden – the Tornedalians – and their language has developed separately from the Finnish language spoken in Finland.

There are about 25,000–75,000 Tornedalians (See Arola et al (2013) and Laakson et al (2016)) living in the following administrative territories in northern Sweden: Haparanda, Övertorneå, Pajala, Kiruna, Gällivare and Kalix, but also in Umeå, Luleå and Stockholm. Only a fraction of them still speak Meänkieli and they are mostly middle-aged or aging. This is living proof that this minority has been subjected to policies of language assimilation; most young people in the Torne Valley consider it the language of the old, or simply part of a world that is past.

Northern Sweden has generally been severely marginalized and, seen from Stockholm, it has been – and still is – often considered an extraneous region, inhabited by people speaking foreign languages: Sámi and Meänkieli. At the same time Meänkieli has also been marginalized in the Finnish official discourse as it is only considered a dialect in Finland, while it has been an officially accepted minority language in Sweden since 2000.

There are several reasons for the marginalization of the Torne Valley and its cultural heritage. Firstly, there have been economic challenges with the sparse population and the valley being abandoned because of lack of jobs. Secondly, there has been cultural marginalization through negative attitudes towards the minority language from the Swedish majority population, from Finnish-speakers in Finland, and even from some Tornedalians who have become Swedish speaking. There has additionally been a disparity between the formal acceptance of linguistic rights on the one hand, and these being put into practice. For example, there remains a lack of educational provision in Meänkieli in Sweden even though it has been an officially accepted minority language since 2000. While there has perhaps been greater recognition of it in recent years, there remains little public awareness of the importance of using Meänkieli.

Bengt Pohjanen – a multilingual writer

No one can be said to have done more for the Meänkieli language and literary scene than Bengt Pohjanen, who was born in 1944. Pohjanen’s mother tongue is Meänkieli but the educational system at the time he was a child was in Swedish – and still to this day it is not possible to receive schooling in Meänkieli. At the beginning of his career, he wrote in Swedish and his first novel, which was published in 1979, was Och fiskarna svarar Guds frid (And the fishes/fishermen answer God’s peace). It was not until an international seminar in Stockholm on ‘New Writing in a Multi-Cultural Society’ in October 1985, where he met the likes of Salmon Rushdie, that he discovered there were other writers who wrote in a language other from their mother tongue:

“Colleagues came from Africa, from the Caribbean Islands, from India, Japan and many other places. There were a lot of us bound together by our mutual experiences of living along the border…I felt close to them even though they were living in faraway places. They seemed to be my relatives, even if the colour of their skins was different from mine. I realized then that the world was not monolingual. It was thereafter that I wrote my first Meänkieli novel – in my own tongue.” (Page 8 of the Foreward of the Hungarian version of Bengt Pohjanen’s The Smuggler King’s Son from 2011).

Despite being educated in Swedish and having to rediscover his mother tongue as a young adult, almost every aspect of his body of work demonstrates that, for Pohjanen, Meänkieli takes priority over the other languages.

First novel in Meänkieli

Pohjanen is very versatile in that his work spans many different genres, including novels, poems, lyrics, essays, dramas, feuilletons, texts for musicals, short stories, as well as translations into, for example, English, German, French, Russian, Livonian and Karelian.

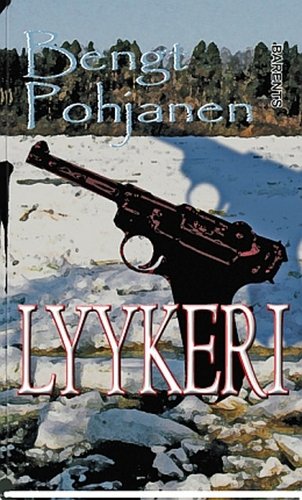

Pohjanen is also the author of the first novel ever written in Meänkieli: Lyykeri, from 1985 (The Luger), as well as the first drama Kuutot, from 1987 (The Kuutto Family). His work suggests that literature can provide the individual with the opportunity to share in the culture of their own people or ethnic group as well as their collective memory. He does not hide away from telling people about the marginalisation of the Meänkieli culture in Sweden and Finland. Other key themes include the individual’s experience in sharing the same fate or being different, as well as strategies used by minorities in societies which exclude them.

Creating a past: Literature reclaiming history

While the roots of Meänkieli literature can be traced back to the 17th century, it did not really develop until the last part of the 20th century, thanks mainly to Pohjanen. Pohjanen considers that intellectuals in general, and artists in particular, have a double mission of uncovering the historical roots of their ethnic group’s collective identity as well as its uniqueness. A central element of Pohjanen’s past-creating activity is the notion that Meänmaa is more than just a geographical area populated by Finno-Ugric people; importantly, it is also a virtual cultural space with an imagined Tornedalian community, their common identity and a shared Meänkieli cultural heritage, including the diaspora and Meänkieli-speakers outside the Torne Valley. In Pohjanen’s opinion, the history of the Meänkielis cannot be considered to be the same as the history of Sweden or Finland, it has to be written from the point of view of the minority and it is not of any less value.

In a paper from 2009, Anne Heith calls attention to the fact that Pohjanen deconstructs the boundaries of the imagined communities imposed by the Swedish majority discourse: “One aim of Pohjanen’s text is to provide a critical examination of the construction of a national culture and identity and of the history of the colonisation of Norrland. This is performed by a presentation of an alternative history through a deconstruction and negotiation of the boundaries of imagined communities which have shaped historiography based on homogenising nationalism.” (Page 216, Heith, 2009).

"an alternative history through a deconstruction and negotiation of the boundaries of imagined communities which have shaped historiography based on homogenising nationalism." (Heith, 2009)

The concept of the "alternative history" of Meänmaa can be traced through all Pohjanen’s works. His best known work written in Meänkieli is Jopparikuninkhaan poika (The Smuggler King’s son) (2009), the first volume of his autobiographical novel. He also wrote it in Swedish (2007) and it has been translated into Finnish, Hungarian and English. The novel deals with painful memories including ethnic, linguistic and minority issues. However, he manages to deal with them in a carthartic manner due to the warm and light writing style that has a healthy dose of humour.

The cultural heritage of a minority

Re-creation of the past – functioning also as self-creation in Pohjanen’s work – is an integral part of the author’s activity in creating a world on the basis of one’s mother tongue. He does not merely have an aesthetic aim, but seeks to create – or re-create – an alternative past seen from the minority point of view, and in the minority language. It is the history of Meänmaa Pohjanen writes about again and again in his literary and journalistic works. And while he is working on awakening the collective memory of his community, he is also trying to understand his own place and role in it. He takes a different historical approach from other writers on the western bank of the Torne Valley, who generally only write in the dominant language of Swedish – although some use a few Meänkieli words in their texts. Some writers and commentators do not see the significance of persisting with the Meänkieli language. Others, like Pohjanen, believe that the literature of the Torne Valley should encompass works written by authors from both the Swedish and the Finnish banks of the river. Pohjanen also seeks to create a kind of “third room of the frontier” as he calls it in his autobiographical novel (Jopparikuninkhaan poika/ Smugglarkungens son/ The Smuggler King’s Son); an autonomous literary world which is beyond national borders.

Prominent literary work by Bengt Pohjanen to date

- Kotirannan jalanjäljilä [The Footprints of my Homeshore] (Barents E-books, 2020).

- Murhaballaadia Vaslav Havelin putkassa [Murder Ballad in Vaslav Havel’s Jail] (Barents Publisher, 2019).

- Vaihettaa kieltä, vaihettaa naamaria [Language Change, Mask Change] (Överkalix: Barents Publisher, 2019).

- Keksin runo-Kexis kväde [The Poem of Kexi] (Barents E-Books, 2019).

- Kylmät hypyt, Jerusalemmin tansit [Cold Jumps, The Dance of Jerusalem] (Barents Publisher, 2018).

- Hauskoja piruja. Väylänvarren trilogia.[Funny Devils. The Trilogy of the Torne Valley] (Barents Audio Books, 2017).

- Kolme näytelmää (Antigone, Kuutot, Bara en ettöring) [Three dramas: Antigone, The Kuutto Family, Only One Penny] (Barents Publisher, 2017).

- Korpelalaisuus [The Korpela-Movement] (Elib, Barents E-Books, 2014).

- Faravidin maa [Faravid’s Realm] (Överkalix, Barents Publisher, 2013).

- Joulun taikaa Kassasta ja muita tarinoita [The Magic of Christmas in Kassa and other stories] (Barents Audio Books, 2012).

- ‘Kieli keskelä suuta’ [The Tongue in the Middle of the Mouth] (Tornedalica, 61, 2011).

- Jopparikuninkhaan poika [The Smuggler King’s Son] (Överkalix: Barents Publisher, 2009).

- Murhaballadi [Murder Ballad] (Ylikainus/Överkalix: Barents Publisher, 2008).

- Lyykeri [The Luger]. (Ylikainus/Överkalix: Förlaaki Kamos, First edition 1985, Second edition 1986, Third Jubilee Edition 2005).

- Saksan liekit polttava – tarina evakosta 1944 [The Flames of Germany Burn – A Story about the Evacuation in 1944] (Barents Publisher, 2004).

- Väylänvarren trilogia / Tornedalstrilogin [The Trilogy of the Torne Valley]:

- Mettäperän pyhät, Meänmaan manalaiset [The Holy People of the Forests]. (Överkalix: Barents Publisher, 2003).

- Kiveliön röykyttäjät, Korpien kolkuttajat [The Strikers of Wasted Land, The Knockers of the Desert] (Barents Publisher, 2003).

- Jerusalemmin tansit, Kaanan häät [The Dance of Jerusalem, The Wedding of Canaan] (Barents Publisher, 2004).

Further reading

- Anne Heith, ‘Voicing Otherness in Postcolonial Sweden. Bengt Pohjanen’s Deconstruction of Hegemonic Ideas of Cultural Identity.’ In The Angel of History. Literature, History and Culture. ed., Vesa Haapala– Hannamari Helander et al. (Helsinki, 2009) pp. 140–147.

- Bengt Pohjanen, Smugglarkungens son. Norstedts. 2007. (Original in Swedish). Hungarian translation: A csempészkirály fia. Enikő M. Bodrogi (Kolozsvár/Cluj: Koinónia, 2011). English translation: The Smuggler King’s Son. Betty Léb. (Överkalix. Barents Publisher, 2017).

- Johanna Laakso, Johanna Sarhimaa, Sia Spiliopoulou Åkermark, & Reetta Toivanen, Towards Openly Multilingual Policies and Practices: Assessing Minority Language Maintenance Across Europe. (Bristol, Buffalo, Toronto: Multilingual Matters, 2016).

- Enikő Molnár Bodrogi, 'The Voice of a “Tongueless” Periphery'. Revista Româna de Studii Baltice şi Nordice [The Romanian Journal for Baltic and Nordic Studies] 6, 1 (2014) pp. 191–205.

- Laura Arola, Elina Kangas, & Minna Pelkonen, Meänkieli Ruottissa. Raportin yhtheenveto ELDIA-projektissa. [The Summary of Report of the ELDIA-project.] (Mainz – Wien – Helsinki – Tartu – Mariehamn – Oulu – Maribor: Research Consortium ELDIA, 2013).