Signed languages in the Nordic countries

Sweden was the first country in the world to recognise deaf people as bilingual in 1979, and the other Nordic countries eventually followed suit. But new technologies and the policy of including deaf children in mainstream education has markedly reduced the use of signed languages in some of the Nordic countries in recent years.

What is a signed language?

Signed languages are languages that are used by people who are deaf from birth and by their families, their friends and people who work professionally with them. They arise when deaf people get together, or in areas with a high percentage of congenital deafness. They may be imported from a different country and introduced in a school for the deaf, perhaps leading to their alternative development from the original.

Signed languages are created primarily by deaf children based on gestures and things that they see in their surroundings. Human hands can imitate shape and movement, the body and face, objects and emotions, and more abstract notions such as love can be expressed through, for example, pressing hands to your heart. When deaf people get together, they start using each other’s signs and develop new ones. Gradually ways of expressing statements, questions, exclamations etc. develop into standard sentence patterns, partly influenced by the majority spoken languages.

The rise and development of signed languages in the Nordic countries

There is some evidence of scattered usage of signed languages in the Nordic countries from the 18th century. But the rise of the Nordic signed languages reflects the political situation in the Nordic countries in the 19th century with a split into two different “language families”. The reason for the split is that the signed languages of the Nordic countries arose primarily in schools for deaf children in Denmark and Sweden in the early 19th century and were later exported to the other areas. The western group consists of Danish Sign Language (DTS, dansk tegnsprog), Icelandic Sign Language (ÍTM, íslenskt táknmál), Norwegian Sign Language (NTS, norsk tegnspråk, norsk teiknspråk), and the dialects of Danish Sign Language used in Greenland and the Faroe Islands. The eastern group consists of Swedish Sign Language (SSL, svenskt teckenspråk), Finnish Sign Language (FSL, suomalainen viittomakieli), and Finland-Swedish Sign Language (FinSSL, finlandssvenskt teckenspråk).

The first schools for the deaf were founded in Denmark in 1807 and in Sweden in 1809. It is generally believed that Danish Sign Language was somewhat influenced by French Sign Language because the founder of the first Danish school visited the earliest French school for the deaf before establishing the Danish school. A deaf teacher, who had also been a student at the Danish school, founded the first school in Norway in 1825, and the first school in Finland was established in 1846 by a deaf teacher who had been a student at the Swedish school. Deaf children from the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Iceland were sent to Denmark before schools were established in these areas, which happened in Iceland in 1867, in the Faroe Islands in 1962, and in Greenland in 1978.

Official teaching policy pushed signed languages into the private sphere, 1880-1970s

The signed languages were generally used as the language of instruction in schools for the deaf up until the last decades of the 19th century, during which time the staff also included deaf teachers. But, partly influenced by teaching methods in Germany and partly by a general trend from 1880 in Europe in favour of what is called the oralist method, the signed languages were suppressed in Nordic schools from the end of the 19th century. From then up until the 1970s, most deaf children were supposed to learn to speak and lipread. However, the signed languages prospered in the dormitories and in associations and clubs founded by deaf people. Deaf people generally found a deaf spouse, which also strengthened the signed languages.

The Nordic associations for the deaf founded the Nordic Council for the Deaf in 1907 with more frequent meetings being held after 1950. Even before 1950 there were Nordic congresses and sports conventions for deaf people, and later also Nordic summer camps for young people, theatre festivals etc. Attempts at developing a Nordic signed language vocabulary or at least some shared signs failed, as deaf people are as little inclined to change their language as anyone else. Nevertheless, frequent interactions among Nordic deaf people have led to loan signs among the Nordic signed languages.

The golden age of the Nordic signed languages from the 1970s to about 2000

The years from the 1970s to around 2000 may be regarded as the most successful period for the Nordic signed languages in terms of public recognition and the spreading of the languages to many sectors of society and communication domains. Technology made long distance video communication possible, and greater travel opportunities gave Nordic deaf people access to international conferences and universities abroad, opening up for an influx of new ideas about the value of signed languages. Importantly, this also led to identity formation as speakers of minority languages with a particular culture – what was characterised as Deaf culture and Deaf identity with capital D.

Prior to this development, there had been a growing awareness of the failure of the oralist method. Many deaf children did not profit from the teaching. Moreover, linguists started documenting that signed languages had all the richness of structure and potential for new vocabulary as any other language.

With the growing awareness of the importance of a signed language for deaf children, hearing parents started attending signed language courses from the late 1970s. The Nordic governments also started actively supporting the signed languages outside the educational system, for instance, by supporting broadcasted programs in the signed languages and establishing educational programs for interpreters.

Legal recognition of signed languages across the Nordic countries from 1979

Developments in deaf education and the recognition of the signed languages followed different policies in the Nordic countries. Sweden was the first country in the world to recognise deaf people as bilingual in 1979 and, thus, indirectly to recognise Swedish Sign Language as a language in its own right. This led to a policy of bilingual-bicultural education with Swedish Sign Language as the language of instruction and written Swedish as a second language for deaf children. In 2009 Swedish Sign Language was included in a language law. Finland recognises “domestic languages” in its constitution, and Finnish Sign Language was included in the constitution in 1995 and got its own law in 2015. Icelandic Sign Language was declared deaf people’s first language by the Ministry of Education in 1999, which led to a policy of bilingual education. Icelandic Sign Language was included in a general language law in 2011.

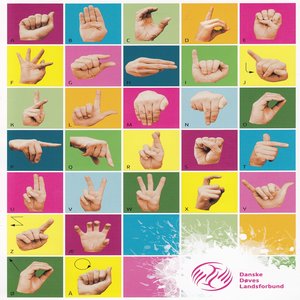

In Denmark and Norway the official recognition of the signed languages followed rather than preceded implementation of a bilingual educational approach. In Denmark the first attempt at bilingual education was instigated in a class in the school for the deaf in Copenhagen in the early 1980s, and ideas about teaching in Danish Sign Language spread to other classes and schools. In 1991 the Danish Ministry of Education issued a ministerial order and a curriculum guide for teaching “sign language” as an academic subject in schools for the deaf. Denmark does not have any legislation about any official language, but in 2006 the UN recognised deaf people’s right to learn a signed language in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, and that same year, the Nordic Council of Ministers adopted a language policy declaration which also recognised signed languages. As a consequence, in 2014 the Danish Parliament passed an addendum to the law about the Danish Language Council which obliges it to work out principles for documenting Danish Sign Language and to provide information about the language. The addendum is often described as the official recognition of Danish Sign Language.

Already in 1985 a Norwegian National White Paper stated that the recognition of “sign language” as a natural language would have consequences for deaf education, and legislation in the 1990s advocated bilingual education for deaf children. In 2009 Norwegian Sign Language was included in a parliamentary proposal to develop a general language law, a law that was passed in 2021.

The era of Cochlear Implantation

From the 1990s hearing screening of all newborns in the Nordic countries and especially the new technology of Cochlear Implants (CI) have changed the linguistic landscape for children who are born deaf or become deaf at an early age. A CI is an electronic device that stimulates the hearing nerve. It consists of an outer part behind the ear and an inner part in the cochlea, and it has improved speech perception considerably for many deaf children, who, with special training, may acquire a spoken language. The reactions to the new technology differ in the Nordic countries.

In Denmark there was a dramatic decline in the number of hearing parents of deaf children enrolled in signed language courses in the period 2000-2010. This development was reinforced by the Danish Health Authority’s decision in 2010 to recommend speech therapy for deaf children with CI and the use of “sign language” only by deaf parents of deaf children. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education adopted by UNESCO in 1994 further supported a movement away from providing deaf children with the opportunity to acquire a signed language as it advocates inclusion of children with disabilities in mainstream schools. In Denmark the number of deaf students in special schools went down from almost 350 in 2002 to about 50 in 2020. Today the majority of Danish deaf children are included in mainstream schools, which do not offer any courses in Danish Sign Language. As a consequence, the number of speakers of Danish Sign Language is being reduced continually.

The Danish government still advocates the use of Danish Sign Language with deaf children who cannot learn to speak by means of the new technologies. Moreover, the support of Danish Sign Language in contexts for adults has not diminished. For instance, deaf speakers of Danish Sign Language are entitled to interpreters in educational and social settings and at the work place. In 2019 the government decided to support the online Danish Sign Language Dictionary financially for a period of three years.

At the Nordic level, TegnTube, a website with information about the Nordic sign languages is supported financially by the Nordic Council of Ministers and Nordplus, an organization that works for cooperation between the Nordic and Baltic countries in the area of education.

In Sweden, the early emphasis on bilingual-bicultural education and deaf children’s right to acquire Swedish Sign Language is maintained in the schools for the deaf, and mainstreamed deaf children are offered courses in Swedish Sign Language, in some cases by means of distance learning. However, especially the parents’ association has advocated a stronger emphasis on spoken Swedish. As in Denmark and Sweden, the Norwegian legislation on education of deaf children has not changed since the 1990s, but the special schools for deaf children have been closed because most deaf children are now in mainstream schools. Nevertheless, a number of these children are still offered courses in Norwegian Sign Language in contrast to what is seen in Denmark.

How many speakers are there in the Nordic countries?

There has never been a census of deaf speakers of the signed languages in the Nordic countries. It is estimated that there are currently about 5,000 deaf speakers of Danish Sign Language, 4,000-5,000 of Finnish Sign Language, 4,000 of Norwegian Sign Language, 8,000-10,000 of Swedish Sign Language, between 200 and 300 of Icelandic Sign Language, and about 90 of Finland-Swedish Sign Language. To these numbers we may add hearing speakers for whom the signed languages may not be their primary language, especially family members and friends and professionals such as interpreters, social workers, teachers, and priests.

Further reading:

- Brita Bergman & Elisabeth Engberg-Pedersen, ‘Transmission of sign languages in the Nordic countries’, in D. Brentari, ed., Sign languages (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010), pp. 74-94.

- Elena Koulidobrova & Rannveig Sverrisdóttir, ‘How to ensure bilingualism/biliteracy in an indigenous context: The case of Icelandic Sign Language’, Languages 6, 2 (2021), pp. 1-24.

- Fred Karlsson, The languages of Finland 1917-2017 (Turku: Lingsoft Inc, 2017).

- Helle Skjoldan, Status på dansk tegnsprog [The current state of Danish Sign Language] (Danske Døves Landsforbund, København, 2021).

- Hilde Haualand & Ingela Holmström, ‘When language recognition and language shaming go hand in hand: Sign language ideologies in Sweden and Norway’, Deafness & Education International 21, 2-3 (2019), pp. 99-115.

- Jesper Dammeyer & Stein Erik Ohna, ’Changes in educational planning for deaf and hard of hearing children in Scandinavia over the last three decades’, Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 23, 1 (2021), pp. 114–123.

- Karin Hoyer & Kaisa Alanne, Teckenspråkens och teckenspråkigas ställning i Norden [Sign language and the position of sign language in the Nordic countries] (Finlands Dövas Förbund, 2008).

- Kristín Lena Thorvaldsdóttir & Valger∂ur Stefánsdóttir, ‘Icelandic Sign Language’, in J. B. Jepsen, G. De Clerck, S. Lutalo-Kiingi and W. B. McGregor, eds., Sign languages of the world: A comparative handbook (Berlin, Germany, De Gruyter Mouton, 2015) pp. 409-429.

Links:

- The Nordic Languages (The Nordic Council and the Nordic Council of Ministers website).

- Website for the Nordic Signed Languages (In the Nordic languages)

- Sign Tube for the Nordic countries (In the Nordic languages)