Swedish speakers in Finland

Finland has two official languages, Finnish and Swedish, as a result of its more than 600-years as part of the Kingdom of Sweden (until 1809). While the Swedish-speaking minority has remained relatively small, the Finnish Constitution and other relevant legislation guarantee them the same language rights as Finnish speakers. This has resulted in bilingual public and private services and organisations, and the relationship between the two language groups has led to both friction and been a source of artistic inspiration.

Swedish-speaking Finns have Swedish as their first language, although it has become increasingly common to grow up in bilingual households. The presence and roles of the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland have, at various times, caused significant tensions in the formation and maintenance of a Finnish national identity. On the one hand, some Swedish-speaking Finns (‘Finland Swedes’ or Finlandssvenskar) feel harassed or disrespected on account of their Finland-Swedish identity. On the other, some Finnish-speaking Finns resent what they see as the outsized protection and concern given to a linguistic minority. The country’s bilingualism has been, and continues to be, a source of tension between Swedish and Finnish speakers. This tension has been present to varying degrees in Finnish society since the rise of Finnish nationalism in the late nineteenth century. As early as the 1980s, Finland-Swedish migration to Sweden was seen as a serious societal problem, contributing to the possibility of the minority disappearing entirely, although in recent years this issue has been discussed only rarely.

Stereotypes

A recurring topic in Swedish-language Finnish media is the contemporary relationship between the two national language groups. Finnish-speakers are asked to describe what they think of the Swedish-speaking Finns. Responses often reveal stereotypes about Finlandssvenskar, including that they are wealthy, more intellectually or culturally oriented, more arrogant on average, or that they identify more with Sweden rather than Finland. Similarly there is a frequent stereotypical criticism that Swedish-speaking Finns are isolationist and more interested in their own minority community than Finland itself. Some of these cultural stereotypes have clear links to the history of Swedish-speakers in Finnish society.

Rights of Swedish-speaking minority written in constitution

Despite the small number of Swedish-speakers in Finland, the group long exerted a disproportionate amount of control over the political life of the realm. In 1880, Swedish-speaking Finns comprised 14.3% of the total population of Finland; by 2017 the percentage had dropped to 5.2%, or about 289,000 people, according to Statistics Finland. Nonetheless, Finland’s constitution dictates that both Finnish and Swedish are the country’s official languages and thus equal in status. Each Finnish citizen may choose to communicate with authorities in either Swedish or Finnish. Church services occur in both languages, as the Evangelical Lutheran Church has both Swedish- and Finnish-speaking parishes. Individuals who are conscripted to serve in the military are likely to be placed in a unit of soldiers who share the same native language.

Bilingual municipalities

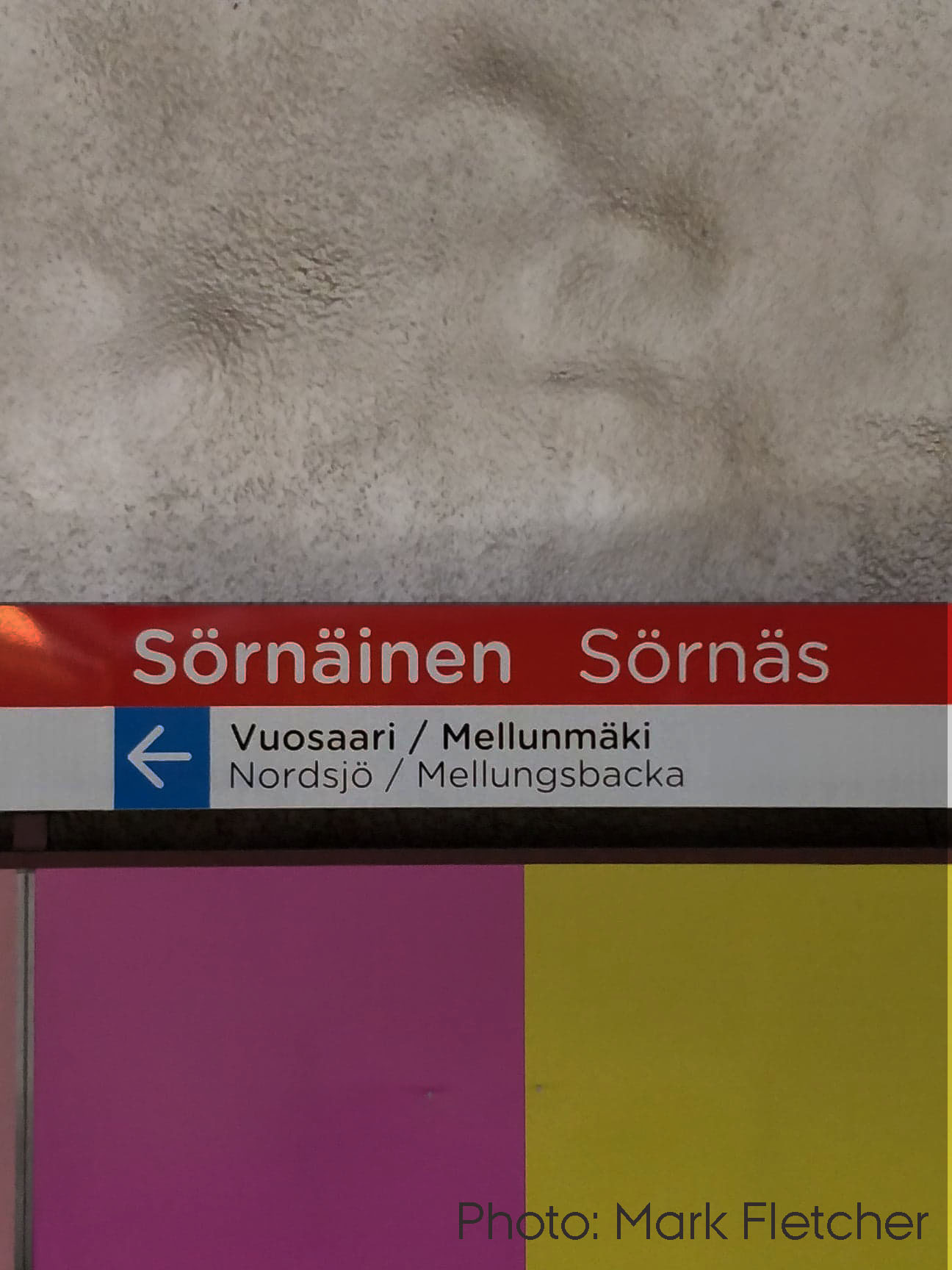

Finnish municipalities can be bilingual or monolingual, depending on the composition of their population and the language in which residents are registered with the government. Most Swedish-speaking Finns live in bilingual municipalities. Monolingual local governments have slightly fewer legal responsibilities in terms of providing all services in both official languages. Most Swedish-speakers in Finland are concentrated in the coastal areas of Nyland (Uusimaa), Åboland (Turunmaa), Ostrobothnia (Österbotten, Pohjanmaa), and Åland (Ahvenanmaa). The Åland islands are an autonomous part of Finland and as of 2017 the only municipality that is registered as monolingually Swedish-speaking.

Political representation of Swedish-speaking minority

There is one political party in Finland that explicitly defines itself as the party of Swedish-speaking Finns, namely the Swedish People’s Party (Svenska folkspartiet, SFP). Founded in 1906, the SFP is one of the oldest political parties in Finland. Another means of representation, the Swedish People’s Assembly (Svenska Finlands folkting) advocates for the interests of Swedish-speaking Finns. The members of the Assembly are elected based on the results of nationwide municipal elections. Partly subsidised by the state, the Assembly is actively involved in the preparation of legislation like the most recent Language Act, which came effect in 2004. The official understanding of ‘language’ in the legislative context is almost exclusively a matter of the two official national languages (Finnish and Swedish) and at the constitutional level does not take up the issue of other ‘minority languages’ like Russian, Estonian, and Sámi. As of 2014, speakers of other foreign languages outnumbered Swedish-speaking Finns.

Bilingual schools and universities

As in other aspects of life in Finland, educational opportunities are available in both official languages; private and public Swedish-language schools exist at all levels. Day care and preschool must be available in both languages and are provided by the municipalities. Swedish-speaking Finns may also undertake to study in Swedish at the university level. Åbo Akademi, located primarily in Åbo (Turku) and Vasa (Vaasa) but with activities in Jakobstad (Pietarsaari) and on Åland, is Finland’s Swedish-language university. In addition, the University of Helsinki (Helsingfors) is officially bilingual, while certain schools at the university use Swedish as their working language. Students are required to study the other domestic language (either Finnish or Swedish) but, since 2004, are no longer required to pass an exam in it as a condition of graduation.

Swedish language newspapers and Finland-Swedish literature

There are several city and regional Swedish-language newspapers published in Finland, of which Hufvudstadsbladet, a national daily paper published in Helsinki since 1864, has the largest number of subscribers. The Finnish Broadcasting Company (YLE) is required to provide media services in Swedish in addition to its programmes in Finnish. Swedish-language television and radio programmes, produced both in Finland and in Sweden, are available to the Swedish-speaking community. Additionally, Swedish-speaking Finns have been both active and successful on the literary scene (see Finland-Swedish literature). Some Finland-Swedish authors include Tove Jansson (creator of the Moomin trolls), Bo Carpelan, Jörn Donner, Lars Huldén, and Märta Tikkanen.

Further reading:

- Mia Halonen, Pasi Ihalainen, and Taina Saarinen, eds. ,Language Policies in Finland and Sweden: Interdisciplinary and Multi-Sited Comparisons. (Bristol, Buffalo, Toronto: Multilingual Matters, 2015).

- Ulriks Wolf-Knuts, 'Coping Mechanisms among the Finland-Swedes.' Folklore 124, 1 ( 2013), pp. 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/0015587X.2013.722304.