The Legal Basis of Åland’s Demilitarization and Neutralization

The history of Åland’s legal status reflects key security issues in the area of the Baltic Sea for the last 100 years or more

Summary: From a bridge between two parts of the Swedish realm, to a western outpost of the Russian Empire, to a demilitarized and neutralized part of NATO, the legal status of this autonomous region has far-reaching consequences for the Nordic region.

The Åland Islands are one of the three autonomous regions in Norden (alongside the Faroe Islands and Greenland). They are, population-wise, the smallest of the three, with roughly 30,000 people as opposed to 52,000 in the Faroe Islands and 56,000 in Greenland. Geopolitically they are located in the Baltic Sea region with strong political, cultural and legal ties to Finland and Sweden. The Åland Islands are the only remaining monolingually Swedish-speaking region in Finland and are guaranteed to remain so in public affairs according to international and constitutional law.

Contemporary perspectives on Åland's status

After the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia in February 2022, Finland and Sweden decided to apply for membership of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). This brought up the question of if and how Åland’s demilitarized and neutralized status would be compatible with Finland’s membership in a military alliance. Certain circles in Finnish defense policy making raised their concern over Åland’s status as a potential “military vacuum” claiming, without any evidence, that the lack of military fortifications would constitute a security threat for Finland.

On the Ålandic side, they wanted a seat at the table during NATO-Finland negotiations as a part of the Finnish delegation and that Åland’s demilitarization and neutralization would continue even after Finland joined the alliance. The result was that, regarding Åland, both NATO and Finland accepted the status quo, arguing that the international conventions establishing Åland’s status are still in force, and that "Finland is obligated to protect Åland’s neutrality [sic]” (Finland's Defence Policy Report 2022, page 18) which is not in conflict with Finland’s obligations under the NATO treaty. Despite this apparent certainty, the Foreign Ministry of Finland in 2023 have initiated a legal study of the current status of Åland’s international status pertaining to demilitarization and neutralization. It is currently unclear whether this would be made public, but it appears to be a sign that Åland’s international legal status will be a hot topic for Finnish and Nordic foreign and security policy in the foreseeable future.

But, what does it actually mean to be demilitarized and neutralized? And how did Åland become interesting from a security policy perspective? Åland’s international status is a result of several important international treaties which take us through key historical milestones in the Nordic region.

Key legal developments pertaining to Åland’s military status

1856 The Demilitarization Treaty

1921 The League of Nations Decisions

1940 Finnish-Soviet Bilateral Treaty

1947 Paris Peace Treaty

1991 Autonomy Act of 1991

1992 Renewal of the Finnish-Soviet Bilateral Treaty

1994 The Åland Protocol and the European Union

2009 The Lisbon Treaty

2022-2023 Finland’s NATO Process

1856: The Demilitarization Treaty

The Åland Islands, alongside mainland Finland, were an integrated part of the Kingdom of Sweden for roughly six centuries. With the loss of the eastern part of the Swedish realm to the Russian Empire in 1809, the Åland islands became the westernmost outpost of Russia. In other words, Åland became a “loaded pistol directed at Sweden's heart” (a phrase supposedly used by Napoleon). This posed a particular problem for Sweden, which now had a potential hostile power stationed near Stockholm. Russia undertook construction of military fortification in the early 19th century (most notably, the Bomarsund fortress), however the outbreak of the Crimean war in 1853 prevented the realization of the fortification plans when the unfinished fortress was bombarded by British and French forces. As a result of the war, a treaty was signed in Paris on March 30, 1856, between France, Great Britain and Russia. This treaty is often referred to as the “Convention on the Demilitarization of the Åland Islands” (Demilitariseringsfördraget in Swedish), and is fairly short, consisting only of two articles which state that “...the Åland Islands shall not be fortified, and that no military or naval establishments shall be maintained or created there”.

"Neutral” or “neutrality” tends to refer to a policy of non-alignment and non-engagement with war activities. It is more accurate to say that the territory of Åland has been "neutralized" so as to create an international obligation to keep the territory outside the theatre of war according to customary and treaty-based law. This has not been considered a hinder towards Finland’s membership of NATO nor has NATO membership affected the validity of Åland’s demilitarized and neutralized status.

Tug of war between Finland and Sweden resulted in neutralization

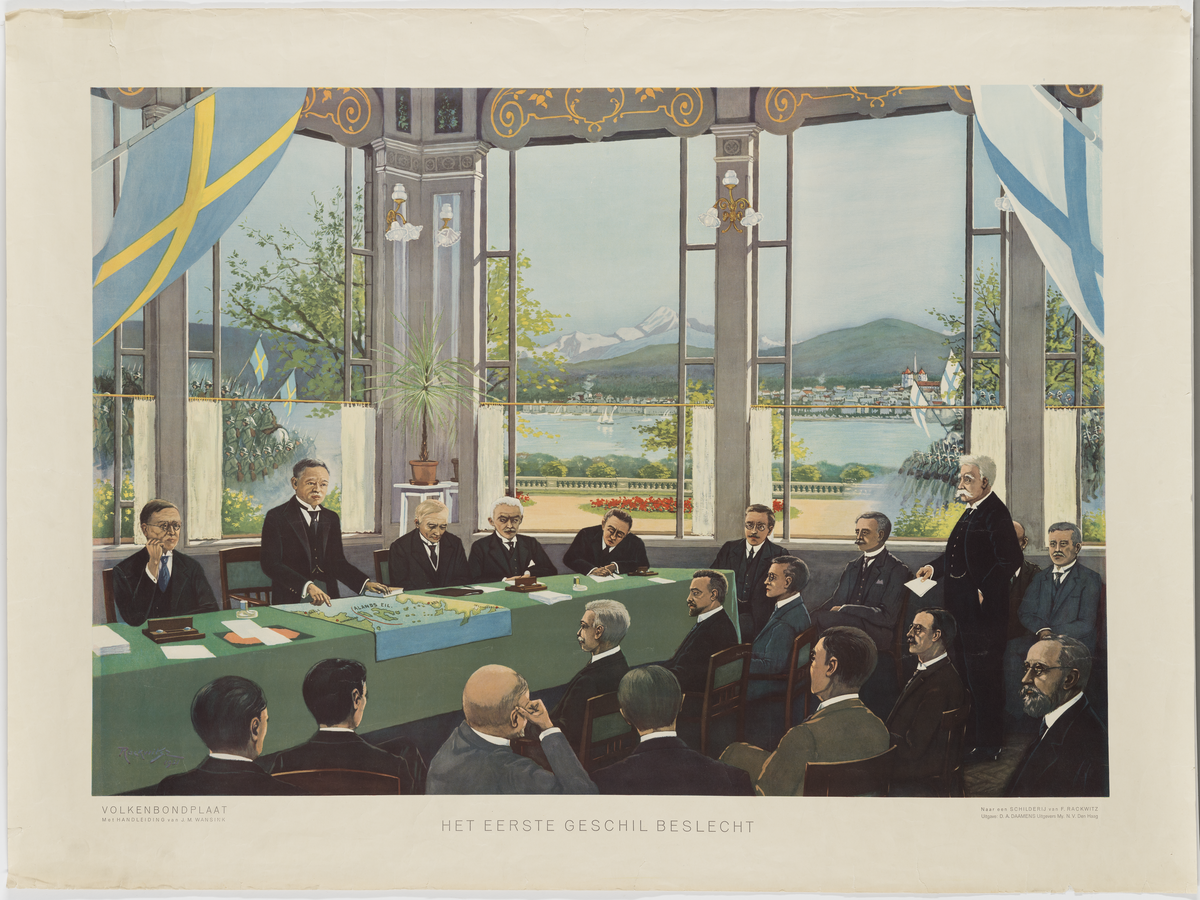

As a result of the struggle of the Åland Movement (a group of Ålandic activists advocating for an annexation of the islands by Sweden called Ålandsrörelsen) between 1917-1921, the Åland Islands once again became an international question. As a result, the territorial dispute between Finland and Sweden was brought before the newly established League of Nations (LoN) in 1921 by the United Kingdom.

After long deliberations and considerations of all factors deemed relevant by the League, they finally issued a decision on June 24, 1921. This decision included a recognition that the Åland Islands belonged to Finland, provided that Finland would commit to addressing the cultural anxieties of the Swedish-speaking Ålanders, and that Sweden’s security concerns would be addressed with a separate convention regarding the neutralization of the islands. The Convention on the Non-fortification and Neutralization of the Åland Islands was signed among 9 states (Germany, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Britain, Italy, Poland, Sweden) in October 1921. In this treaty, Finland not only undertook to maintain the conditions demanded by the 1856 Demilitarization treaty, but also to uphold a regime designed to keep the islands outside of the theatre of war. It should be noted that the Soviet Union was not a signatory power of this treaty as they were not a member of the League of Nations at that point.

Åland’s potentially strategic location during the Second World War

After a failed Swedish-Finnish attempt to remilitarize the Islands in 1938, Åland was once again a matter of international politics as a part of the Second World War. Finland fought against the Soviet Union in the so-called Winter War and as a result, a treaty regarding the island’s status was signed between them on October 11, 1940. This bilateral treaty reaffirmed the non-fortification and demilitarized status of the islands’ territory and, perhaps more importantly, allowed for the Soviet Union to establish and maintain a consulate in Mariehamn, with the intention to supervise the application of this treaty.

The status of Åland was revisited after the conclusion of the Second World War. Article 5 of Part II (political clauses) of the Paris Peace Treaty in 1947 notes that “The Åland Islands shall remain demilitarized in accordance with the situation as presently existing”. Additionally, Part II (Military, Naval and Air Clauses) allowed “allied or associated powers” the right to notify Finland about which pre-war bilateral treaties with Finland they wanted to maintain. As a result, the Soviet Union notified Finland of their desire to maintain their bilateral treaty dating back to 1940 regarding the demilitarization of the Åland Islands.

Finland and Russia reconfirmed Åland’s status post-Cold War era

The Cold War period proved an era of remarkable stability for the military status of the Åland Islands. With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the increased impetus for regional integration in Europe, the relevance of Åland’s demilitarized and neutralized status was questioned by some military circles in Finland. However, the ultimate policy output would contradict these critical ideations. In 1992, the Russian Federation and the Republic of Finland signed a treaty, confirming the continued validity of the 1940 treaty in the post-Soviet era, meaning that the bilateral (Finnish-Russian) dimension of the regime governing the demilitarization and neutralization of Åland would continue. Russia continued to maintain a consular presence on the islands accordingly.

Åland and the European Union

According to the Autonomy Act of 1991, Åland has a right to reject the application of (on Åland’s territory) international treaties that contravene Åland’s legislative competences. Finland applied for membership in the European Communities in March 1992, following Sweden’s decision in October of the previous year. The approval of the Parliament of Åland was necessary for Finland to ensure the application of Community Law on the territory of Åland. This meant that Finland had to seriously consider the positions of the Åland Government and Parliament, which might not necessarily be convergent with those of Finland. This resulted in a separate protocol (no.2) attached to Finland’s accession treaty to the European Union, known as the Åland protocol. The preamble reads “Taking into consideration the special status that the Åland islands enjoy under international law, the Treaties of which the European Union is founded shall apply to the Åland islands with the following derogations…”. The two derogations allowed the Åland Islands to:

- Maintain regulations regarding the application of regional citizenship (hembygdsrätten). This placed certain restrictions placed on non-residents of Åland (in practice Finnish speakers with no prior connection to Åland) regarding land ownership and eligibility for political office.

- Be exempt from the tax harmonization process in the EU. This was primarily about allowing ferries to continue selling tax-free merchandise on ferries to and from Åland.

These two derogations allowed the Åland government to ultimately adopt a position favourable to EU membership, something that has proved elusive for Greenland and the Faroe Islands which have been critical towards the EU’s fisheries policies.

The international legal status of Åland was once again brought up in the discussions regarding the Lisbon Treaty in 2009, a new “constitution” for the EU. The reasons why Åland’s opinion carried any political weight were the same as in 1994: the provisions of the Autonomy Act for Åland and Finland’s political concerns regarding the application of the Lisbon Treaty on the entirety of its territory. In Part Seven (General and Final Provision) of this new treaty, the provisions of the so-called Åland Protocol were declared to be valid in the new European legal order just as before.

In conclusion, the Åland Islands were demilitarized and neutralized as a result of complex power politics in the previous centuries. They have remained so through significant historical shifts in the region, as a result of mutual political will on all relevant sides to keep the islands demilitarized and neutralized. In a political context where emotions run high, the Åland Islands are an important case study in the continued value in rules-based international order despite high tensions elsewhere.

Law and political science can shed light on current intractable issues

This article is published in a response to readers’ interest in security issues and the autonomous territories of the Nordic region.

Further reading:

-

Saila Heinikoski, “The Åland Islands, Finland and European Security in the 21st Century”, Journal of Autonomy and Security Studies, Vol.1,1, 2017, pp. 8–45

-

Sia Spiliopoulou Åkermark, “The puzzle of collective self-defence: dangerous fragmentation or a window of opportunity? An analysis with Finland and the Åland Islands as a case study”, J Conflict Security Law Vol. 22, 2, 2017, pp. 249–274

Links:

- The full texts of the treaties can be found here: https://kulturstiftelsen.ax/app/uploads/2020/07/english-3-3-1.pdf