Arctic Council

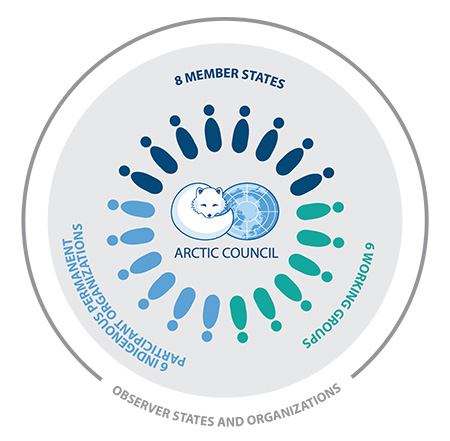

The Arctic Council was established in 1996 by the Ottawa Declaration with the intent of fostering “cooperation, coordination, and interaction between the Arctic states.” Member parties work together towards the sustainable development of the Arctic region. Member states, Permanent Participants and others, including observers, meet formally in Ministerial Meetings every two years to discuss and agree on environmental, social and, economic policies. Observer status is granted to non-Arctic states and organisations by the Council at Ministerial Meetings.

The member countries of the Arctic Council are Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, the Russian Federation, Sweden and the United States. The Faroe Islands and Greenland, and the island of Åland are also included in the Council, albeit via Denmark and Finland respectively. The Council evolved from a history of close collaboration among the Nordic countries; the Nordic countries had a passport union and common labour market even before the creation of the European Union. The Nordic Council was created in 1952 as an inter-parliamentary forum and the Nordic Council of Ministers in 1971 which was established as a formal inter-governmental body. Both these councils continue to have close ties to the Arctic Council and the Nordic Council of Ministers has observer status. In 1991 representatives from the five Nordic countries and the other arctic governments gathered to sign the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy (AEPS), the first step toward the creation of the Arctic Council. The Council was created in 1996 with the signing of the Ottawa Declaration.

Permanent Participants

Governments in the Arctic region have joined with indigenous peoples in monitoring and assessing issues of common concern, including climate change, pollution, oil and gas development, emergency preparedness, and sustainable development. Indigenous peoples are represented as Permanent Participants of the Council by six international organisations, namely:

- Aleut International Association;

- Arctic Athabaskan Council;

- Gwich’in Council International;

- Inuit Circumpolar Conference;

- the Sami Council; and,

- the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North.

The Indigenous Peoples’ Secretariat is located in Copenhagen, Denmark. Permanent Participants have the right to address the meetings of the Council, to add agenda items, and to propose collaborative projects. The Permanent Participant-indigenous members are assured a greater voice here than in many other international platforms. Their status in the Council, however, does not confer any legal recognition of them as tribal or ethnic groups and decision-making lies solidly in the hands of the eight member countries. Ministers from the member countries come primarily from their Foreign Affairs, Northern Affairs, or Environment agencies. The Council meets every other year and its chairmanship rotates every two years among the member states. A Secretariat, located in Tromsø, Norway, handles the administrative affairs of the Council, including maintenance of the website and the dissemination of reports and miscellaneous documents. The Council has no projects budget; projects are funded by the member states and those states are also responsible for enforcing guidelines and assessments.

Observers

Observer status has been a point of concern by indigenous groups whose concern is that non-Arctic states and organisations diminish the influence of indigenous groups in the Council. Observer status has been granted to at least a dozen countries and numerous non-governmental, intergovernmental, and inter-parliamentary organisations. The International Red Cross Federation, the UN Development Programme, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature are among the non-arctic observers. The Nordic Council of Ministers also has an observer role on the Arctic Council and provides it with reports, such as, the Arctic Biodiversity Assessment.

An overview of the plenary meeting room during the Senior Arctic Officials' meeting in Juneau, March 2017. Photo: Arctic Council Secretariat / Linnea Nordström (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Working groups

The Arctic Council as a circumpolar forum plays a key role in advancing policies and initiatives to protect the arctic environment. The Council has six working groups:

- the Arctic Contaminants Action Program;

- the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme;

- the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna Working Group;

- the Emergency Prevention, Preparedness and Response Working Group;

- the Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment Working Group; and,

- the Sustainable Development Working Group.

These working groups conduct comprehensive assessments on social as well as environmental issues. The Council draws together Task Forces and Expert Groups as warranted as, for example, the Task Force for Arctic Marine Cooperation and the Expert Group on the Framework for Action on Black Carbon and Methane.

Agreements

The Council has been the forum for the development of legally binding agreements between the eight member states. Examples include:

- The Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic was signed in Greenland in 2011.

- The Agreement on Cooperation on Marine Oil Pollution Preparedness and Response in the Arctic was signed in Sweden at the Ministerial meeting in 2013.

- In 2017 the Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation was signed at the Ministerial meeting in Alaska.

The Nordic Council of Ministers

The Arctic Council shares with the Nordic Council of Ministers an agenda to promote environment-friendly and socially responsible programmes and policies. The Nordic Council of Ministers has an observer role with the Arctic Council and has been influential and supportive of Council initiatives. Together they lobbied heavily in support of the UN Minamata Convention which banned the use of mercury in a host of products and industrial processes. The Nordic countries are often heralded as being at the forefront in waste management and eco-design for new buildings. For example, ’Green Growth the Nordic Way’ is a framework for educating, training, researching, and implementing green methods and technologies, e.g., disposal of plastics and food wastes, and the flexible use of energy. . Members of the Nordic Council have been active participants more recently in climate change negotiations as, for example, calling for global action plans to address global warming.

In words and action, the Arctic Council has frequently been effective in presenting a unified voice on critical issues of both arctic and global significance. In its first decades, the Arctic Council fostered cooperation and good will among its member states. Decisions are based on consensus by the member states acting in full consultation with indigenous groups. Whilst it has come under fire for granting far-removed stakeholders observer status amongst other things, its emphasis on inclusivity, fairness, and collaboration is laudable and could be a useful model in other parts of the world, particularly in areas with marginalised indigenous populations.

Further reading:

- D. Nord, The Arctic Council (Routledge Global Studies Series, 2018)

- D. Nord, The Changing Arctic: Consensus Building and Governance in the Arctic Council (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018)

- M. Byers, Who Owns the Arctic? (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2010)