Finland in (Popular) Geopolitics – An Overview

Meaningful themes from national and world history resurface in modern film and culture.

Summary: With its accession to NATO, Finland reversed decades of geopolitical liminality in 2023. From its declaration of independence through the Cold War, the country functioned as part of a protective corridor dividing Western Europe from Soviet Russia; however, the seeds of its new position as a bulwark against Russian territorial aggrandisement were laid during World War II, a fact underscored by the release of the internationally popular film Sisu set during the Lapland War.

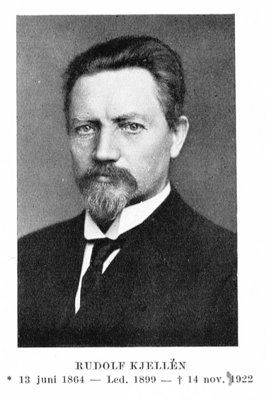

Geopolitics began in Norden. Pioneered by the Swedish geographer Rudolf Kjellén with his 1916 text Staten som livsform (translated into German a year later as Der Staat also Lebenform), Geopolitik emerged as a distinct discipline in the early twentieth century. Geopolitical thinking shaped much of the twentieth century, introducing terms such as the World-Island, Lebensraum, and Rimland Theory. Despite its historical links to the Nazi regime, contemporary geopolitics has been redeemed via successive innovations in its focus, including critical, feminist, and popular turns – each of which has further distanced the discipline from its dark past. With Finland’s accession to the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), Norden is once again at the centre of the geopolitical thinking.

Rebuffing Russia - from independence to the Continuation War

Declaring its independence in 1917, Finland established a model for other polities of tsarist Russia to do likewise. Shortly thereafter, other subaltern nations of the Romanov imperium – including Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland – would follow, alongside other failed attempts at state-building that were short-circuited by the Bolsheviks (e.g. Ukraine, Georgia, and the Idel-Ural State). After its bloody Red-White civil war (1918), Finland – as a ‘border state’ with the new Soviet regime – became the northern bulwark of a geopolitical bloc known by its French appellation, the cordon sanitaire (protective corridor). This zone served to separate the ‘politically diseased’ states of revanchist Germany and Bolshevik Russia, later known as the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Possessing an Arctic coastline before World War II and territory on the threshold of Russia’s former capital Leningrad, Finland’s spatial situation neatly served western European interests, which included preventing the revolutionary ‘contagion’ spreading to the working classes in Birmingham, Rotterdam, and Paris, while also establishing a new market for goods produced in these industrial cities. However, Finland followed most of its fellow Soviet-bordering states down the path to authoritarianism as the politics of Europe trended increasingly towards right-wing reaction in the 1930s – although this period was relatively short-lived.

Sisu – roughly translated as ‘stoic resilience’ or ‘grit’ in the face of extreme adversity; shaped by the country’s harsh northern climate and difficult past, sisu is considered to be the defining national trait of the Finnish nation and a source of (quiet) pride.

World War II proved to be a key inflection point in Finland’s geopolitical positionality. Surreptitiously sold out by Nazi Germany’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Joachim von Ribbentrop on 23 August 1939, Finland found itself in Joseph Stalin’s sights as he sought to reclaim lands lost due to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (1918) as part of a bargain with Berlin. Following the Blitzkrieg on Poland from the west, the Red Army marched into eastern Poland, and shortly thereafter on Finland. In a grand example of sisu, Finns rallied in defence of their territory in the Winter War (1939-1940), an intervention that resulted in the USSR being expelled from the League of Nations.

However, predicting the coming onslaught, a series of fortifications embedded in the terrain known as the Mannerheim Line helped Helsinki fend off the Soviets. Failing to reclaim Finland, Moscow moved on the fledgling republics of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia in the summer of 1940, incorporating the Baltic States into the union as constituent republics, an act that would not be recognised by much of the Western world for the ensuing five decades. A second Finnish-Soviet conflict followed with the Continuation War (1941-1944); in this case, Finland, backed by Berlin, took the offensive reclaiming lost territory and expanding into Soviet Karelia. There would be one further turn, with Helsinki signing the Moscow Armistice reaffirming the 1940 border agreement with the USSR, requiring the country to turn its weapons on the remnants of the Wehrmacht in the Fenno-Scandinavian peninsula in the Lapland War (1944-1945).

Negotiating the Kremlin’s orbit during the early Cold War

Not included in the grand balance-of-power negotiations at Yalta, Finland was left out in the cold when WWII ended. Due in part to the departure of the staunch anti-communist C. G. E. Mannerherim from the realm of Finnish policymaking, the US and UK permitted Finland to slip into Moscow’s outer orbit after the Allied victory over the Axis powers. Under the soft hegemony of the Kremlin yet avoiding being rendered a Soviet satellite due to skilful diplomacy, Finland suffered a four-fold burden in the immediate post-war era:

- the territorial loss of its eastern and Arctic fringes;

- the challenge of absorbing displaced Finns, Ingrians and Karelians from the USSR;

- severe reparations to be paid to Moscow; and,

- its forced rejection of Marshall Plan aid from the United States.

With this confluence in the frame, a new word entered the lexicon of geopolitics: the somewhat derogatory term Finlandization.

Finlandization – in international relations this term harks back to the power Moscow held over Finland after World War II, that is, that a smaller country is independent to all intents and purposes, but is simultaneously unable to go against the foreign policy of a large and powerful neighbour.

Liminality lies at the heart of Finland’s Cold War-era geopolitical identity. Helsinki did not join the Soviet-dominated bloc of states that stretched from Poland to Bulgaria, nor did its situation rhyme with neutral-but-Communist Yugoslavia, which broke with Moscow in 1948. Coincidentally, Finland found itself in the position of a cordon sanitaire in reverse, serving as part of an insulating belt of states positioned against Western influence directed at the USSR. Here, the Finns were charged with absorbing the capitalist, consumerist, cultural imperialism emanating from the London-Washington, DC-Hollywood continuum that trained its sights on the eastern side of the ‘Iron Curtain’ after 1948.

Notwithstanding, Finland would become an important conduit of information into the USSR via Estonia due to geophysical proximity and linguistic commonalities. Four years later in 1952, Finland threw a geopolitical ‘coming out party’ in the form of the XV Olympiad, rescheduled from 1940 due to WWII. Like the USA, Helsinki instituted prohibition in the interwar period, but Finland launched a new product on the world in connection with the games: the long drink (Lonkero). Extending and enhancing the country’s nation brand, this gin-and-grapefruit beverage has grown steadily in popularity, currently taking America by storm.

Finland finds its footing as Norden’s eastern fringe

Despite being the focus of intense international attention for its hosting of the games, Finland remained a singular presence in global geopolitics as the paired presidential administrations of Juho Kusti Paasikivi (1946-1956) and his successor Urho Kaleva Kekkonen (1956-1982) ensconced Finland in an in-between space that was neither fully west nor east, instead forming a terra nullius or, if not a precisely that, a ‘nobody’s land’ of the Cold War via a policy of active neutrality enshrined in the so-called ‘Paasikivi–Kekkonen line’.

Together, these heads of state toed the Soviet line with regards to foreign policy, but towards the end of the twentieth century Finland gravitated into quiet alignment with Sweden. Helsinki and Stockholm constructed a condominium of steely Nordic resistance against what was expected as the inevitable Soviet thrust across the Far North of the European continent. Sweden prepared to repel the incursion, while Finland prepared to absorb it, using its geography to literally ‘bog down’ the invaders, therein affirming the spatial essence of the country as a depleting ‘sink’ based on its deglaciated biome of boreal forests, eskers, fens, drumlins, peneplains, rivers, and lakes. This invasion never came, though the world held its breath when a Soviet submarine ran aground near the Karlskrona naval base in October of 1981, rocking the normally tranquil region. While Sweden had made tactical moves to ostensibly guarantee its informal inclusion in the collective security arrangement associated with NATO, Finland remained at the edges of such protections: an absorption zone for eastern aggression to be depleted as the Red Army lumbered westward towards ultimate defeat at the hands of the Americans, British, and Canadians.

Finland played a role as the USSR wrestled with its future in 1991, relaying the chaos of the August Coup to the outside world via new information and communication technologies which were not being monitored by the anti-Gorbachev junta. In 1995, Helsinki joined its fellow non-Communist continental neutrals Austria and Sweden in acceding to the European Union. With an undivided Europe as the playing field, Finland developed a robust trading relationship with its eastern neighbour, the Russian Federation. For decades, NATO membership was anathema for most Finns; however, international sanctions crashed the rouble after Moscow’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, thus weakening interest in keeping Russian bonds strong. The full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 proved a geopolitical earthquake in eastern Norden. For Swedes, who had long been divided into neat thirds about membership in the western alliance (one-third for, one-third against, and one-third undecided), the needle shifted towards a slight majority in favour. For the Finns who had been decidedly against membership at the end of the 2010s, the message was clear: NATO now!

The Ukrainian connection - Finnish neutrality dies in the Donbas

Sloughing off informal arrangements about collective security with Stockholm, Helsinki manoeuvred the tangled web of barriers to admission – placed on it by Turkey and Hungary – to join the collective security organisation on 4 April 2023, leaving Sweden clamouring to follow by 2024 (with accession finally happening on 7 March 2024). Seemingly overnight, Finland became NATO’s newest member and its most geopolitically-important given its 1,340-kilometre border with Russia. Moreover, the country represented a welcome addition to the alliance given its military spending, formidable armed forces, and a war-readiness honed over decades. Buoyed by the celebrity-prime ministership of Sanna Marin (2020-2023), Finland found a highly receptive audience in the West to its purposely modest charms combined with a century-old resistance to Russian territorial aggrandisement

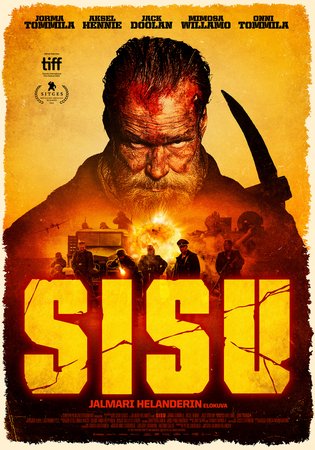

As if on cue, April 2023 saw the US release of Sisu by director Jarlmari Helander. Set in Lapland immediately after the Moscow Armistice when Finland turned against its hitherto-ally Germany, the film focuses a solitary gold miner who finds a motherlode in the Arctic fells before beginning a one-man war against a Waffen SS platoon on their way to Norway with enslaved Finnish women in tow. As the narrative unfolds, we learn that the wizened prospector is a former commando known for his astronomical kill record in the Winter War, earning him the sobriquet ‘Koschei the Immortal’ from the Soviet invaders, thus invoking the nightmarish ghoul of Slavic myth. With his off-screen lethality against Russians established and amplified by a righteous-albeit-gratuitous slaughter of sadistic Nazis on screen, Aatami (Jorma Tommila) fuses elements of the real-life Winter War sniper Simo Häyhä with the American-style cinematic vigilante (e.g. John Rambo, Beatrix Kiddo, John Wick) to establish Finnish sisu as a valuable adjunct to Finland’s geopolitical heft on NATO’s north-eastern front. Terra nullius no more!

Analysing popular culture can help us understand geopolitical events.

This article was published in response to readers' interest in 'Sisu', Finnish history and popular culture.

Further reading:

- Erkki Berndtson, 'Finlandization: Paradoxes of External and Internal Dynamics', Government and Opposition 26,1 (1991), pp. 21-33.

- Henrik Meinander, Mannerheim, Marshal of Finland: A Life in Geopolitics (London: Hurst, 2023).

- Juha Ridanpää, 'Culturological Analysis of Filmic Border Crossings: Popular Geopolitics of Accessing the Soviet Union from Finland', Journal of Borderlands Studies 32, 2 (2016), pp. 193-209.

- Juhana Aunesluoma, 'A Nordic Country with East European Problems: British Views on Post-War Finland, 1944–1948', Scandinavian Journal of History 37, 2 (2012), p. 230-245.

- Pertti Joenniemi, Finland: Always a Borderland? In Madeleine Hurd (ed.), Bordering the Baltic: Scandinavian Boundary-drawing Processes, 1900-2000 (Berlin: LIT Verlag, 2010), pp. 41-68).

Links:

-

‘Finns Don’t Wish “Finlandization” on Ukraine (or Anyone)’. Article by Jason Horowitz in New York Times.

-

‘Logical But Unexpected: Witnessing Finland’s Path to NATO from a Close Distance’. Blog post by Dr Matti Pesu at NATO Review.

-

‘Lonkero: Finnish Drinks Invented for the 1952 Olympics’. Blog post by Adrian Murphy at Europeana.

-

‘The Moscow Coup(s) of 1991: Who Won and Why Does It Still Matter?’. Essay by Ian Bond for Centre for European Reform.