Freedom of the press in Iceland during the Napoleonic wars

An international current affairs publication in Iceland (Minnisverð tíðindi or Noteworthy News) ran for eight years at the turn of the nineteenth century informing all layers of society about political events at a time when censorship was introduced in the Danish Kingdom.

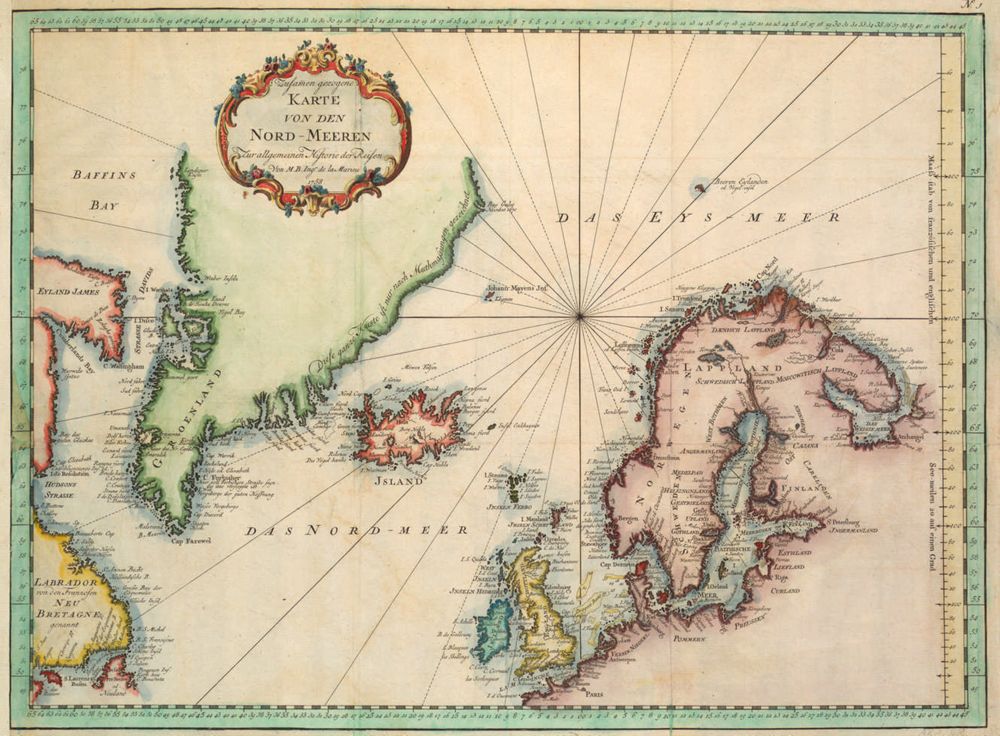

At the height of the Napoleonic Wars and at a time when press freedom was curtailed in Denmark, an interesting development in the opposite direction occured in Iceland, then a province under the Danish Crown: a new, current affairs publication was launched.

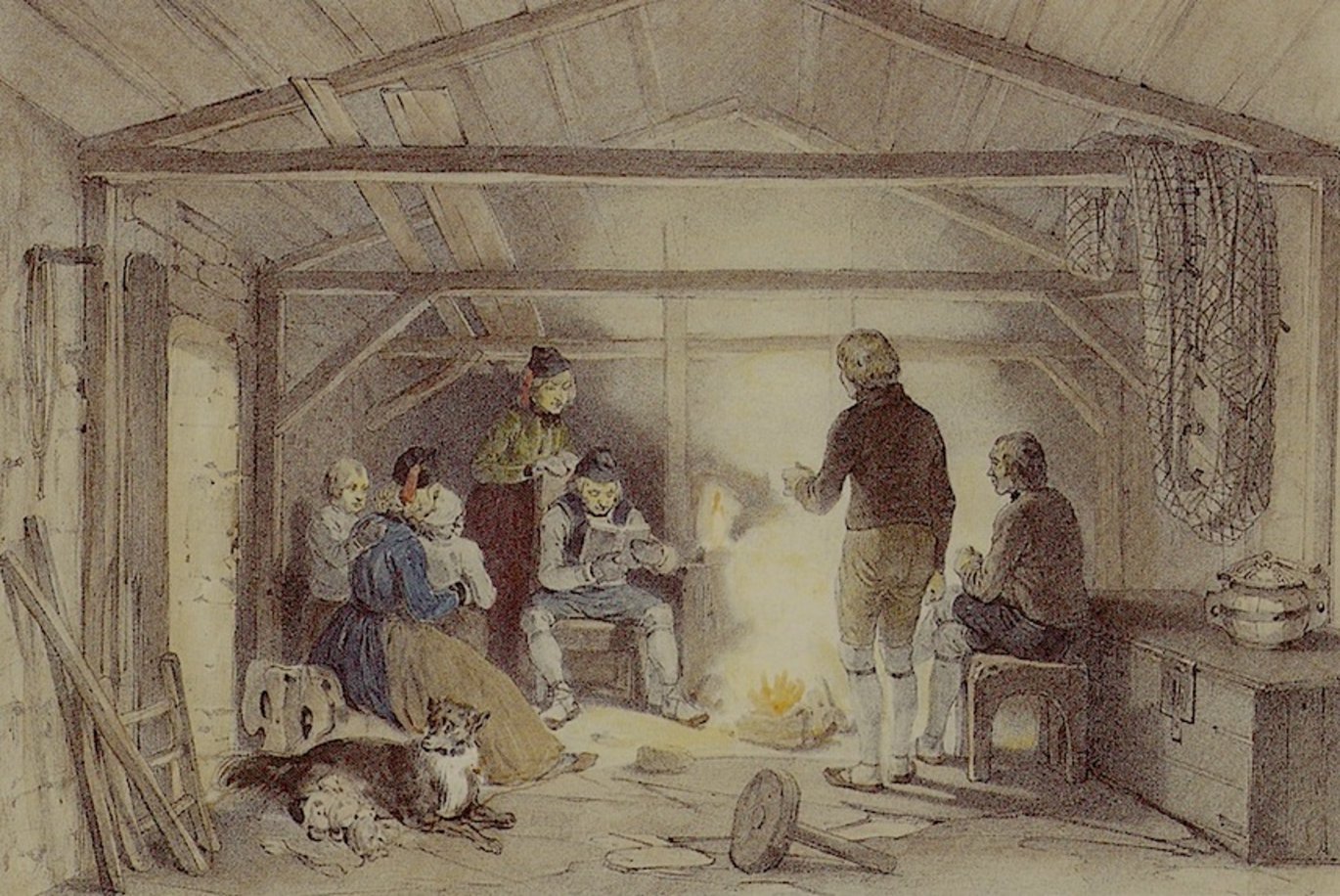

In 1796 the population of Iceland amounted to 43,430 and the literacy level was high although the society as a whole was poor. The title of the periodical, which had the purpose of bringing news and world politics to the eyes of Icelanders, was Minnisverð tíðindi. In Danish, one would say Mindeværdig Tidende. In English I have opted for the translation Noteworthy News. The periodical was published regularly from 1796–1804 and contained detailed narratives of current affairs abroad. Icelanders were given the chance to read about major political developments around the world, not only European affairs such as news from France, England, Ireland, Germany, the Netherlands, Prussia, Poland, Russia and the Ottoman empire, but also items about America, Asia and Africa.

The Icelandic Society flouts censorship laws to bring international news to the people

The publisher of Noteworthy News was a newly founded educational society, “Landsuppfræðingarfélagið”, or the Icelandic Society in English. Its main driver was its president, Magnús Stephensen (1762-1833). Stephensen was editor in chief of Noteworthy News and wrote the first issues himself. He was a rising star in Iceland and became the first Chief Justice of Iceland when the Icelandic High Court of Justice was established in 1801. During the following decades, he was very prominant in Icelandic public life.

The publication of Noteworthy News was expected to be a powerful tool for influencing the Icelandic public sphere which was just starting to blossom. More than one thousand copies were printed which were circulated widely among friends and neighbours. Stephensen knew that membership of the Society would be more desirable if its publications were frequent from the outset. The printing press of the Icelandic Society - which was the only press operating in the country - was thus operated at full capacity from the very beginning. Soon the head printer was near exhaustion from printing large print runs of the periodical as well as of other materials, such as books.

Consequently, it so happened that Icelanders from all ranks of society and in every isolated corner of the country, from farmers, to priests and officials, could read about global events at the same time as censorship laws were being upheld in Copenhagen. Freedom of the press was abolished in Denmark in 1799 with the Trykkefrihedsforordningen, which also applied to the province of Iceland (September 27 1799, Forordning om Trykkefrihedens Grændser, Lovsamling for Island 6, pp. 386–397). But the laws did not deter Stephensen. Strangely enough, upholding the law really fell to one person for practical reasons: Stephensen himself. This was by virtue of him being the person in charge of the only printing press in Iceland as well as the president of the Icelandic Society and, at that time, Iceland was remote from law enforcers at the administrative centre in Denmark (Lovsamling for Island 6, 8 November 1799, pp. 410–411.)

Incendiary subjects were included despite some opposition

Current affairs in Stephensen‘s detailed accounts appeared regularly. Potentially incendiary issues, in Ireland and Poland for example, were not shyed away from, as well as Toussant Louverture and the revolution in „St. Domingo“ (i.e. Haiti). Icelandic readers also got detailed accounts of discussions in the British Parliament and public meetings in London. A Scotsman who visited Iceland during the summer of 1810, Sir George Steuart Mackenzie, gave a fair description of Noteworthy News. In his 'Travels in the island of Iceland during the summer of the year MDCCCX', he wrote that it contained:

a narrative of the political events which had occurred in Europe during the preceding year; a separate article being allotted to the affairs of every state. The narratives appear to be drawn up with much care and considerable minuteness. Under the article of England, as an example, not only are the more important national events described; but the state of parties is accurately detailed; extracts are given from the Parliamentary debates; and notice is taken of many provincial occurrences. (Edinburgh, 1811, pp. 302–303).

Stephensen comments on the progress of the Society in letters to his co-founder and closest co-worker, Bishop Hannes Finnsson, show that he was pleased with the development and make-up of the society during its first years. Its membership consisted of people from all parts of society, i.e. the whole “nation”. Stephensen said it was a miracle in a poor country that the society had acquired more than 1000 members in its first couple of years. According to Stephensen this was “the only example in the history of the world of as pure a sign of enlightenment spirit”. This interest would lead to “eternal glory” for the members themselves as well as their country.

Although the Society was successful at first, it had its opponents. Stephensen was well aware that his political standpoint was not to the liking of all of his fellow countrymen. In a letter to Bishop Finnsson, while preparing the first issue of Noteworthy News for printing he wrote: “I shiver and tremble with fear, as I can be certain that [what I write] will be condemned.” (Lbs. 29 fol. Magnús Stephensen to Hannes Finnsson, 12 Mai 1796 (author‘s translation)).

Stephensen‘s readers weren‘t only farmers and commoners with limited knowledge of political affairs. Stephensen knew that his fellow officials in Iceland, many of whom had studied in Copenhagen, were well informed about political developments in neighbouring countries and that his progressive views, even though written in the Icelandic tongue, would be deemed provocative and could get him into serious trouble with the Danish authorities. The Danes took pride in the preservation of the Icelandic language (Old Norse) and, for example, priests in Iceland preached their sermons in Icelandic.

One of the Danish merchants in Iceland noted (in 1797) that the narrative of the “bloody” French Revolution in the first issue of Noteworthy News was not suitable for members of the Icelandic Society who were peasants. Careless use of concepts such as “liberty” and “equality” in publications for the general public was considered dangerous as the public lacked the necessary background to understand such terms properly. This could have the opposite effect of the intended enlightenment and even lead to a “bloody” revolution (Georg Andreas Kyhn, Nödværge imod den i Island regierende Övrighed (Copenhagen n.a., 1797), p. 257.)

Political education important to publisher

The publishing history of Noteworthy News in Iceland at the turn of the 18th century during the height of the Napoleonic wars gives food for thought. Its publication was daring, but Stephensen was protected in several ways: Very few outside Iceland spoke Icelandic, the island was remote and Stephensen himself, the editor in chief and owner of the only printing press in Iceland, was largely responsible for upholding the censorship laws in the country.

Iceland can be considered an isolated community at the time, but the publishing activity of the Icelandic Society indicates otherwise. It is impressive to consider the publishing role of the president of the Icelandic Society, Magnús Stephensen. While he shivered in fear before releasing the printing press in order to produce the first issue of Noteworthy News, the political education of Icelanders remained a primary driver for Stephensen.

Further reading:

- Ingi Sigurðsson, 'The Icelandic Enlightenment as an extended phenomenon', Scandinavian Journal of History (2010) 35, 4, pp. 371–390.

- Anna Agnarsdóttir, 'Iceland in the eighteenth century. An island outpost of Europe?' Sjuttonhundratal. Nordic Yearbook for Eighteenth-Century Studies (2013), pp. 11–38.

Links:

- Article on The Regulation of Freedom of the Press in 1799 and 1814 on danmarkshistorien.dk (In Danish)