Public opinion on the EU in Iceland since 1980

Back in the 1980s and 90s, support for joining the European Union in Iceland was split into three, a bit like it is today: for, against and undecided. But popularity for the EU has slowly fluctuated between these two periods of time due to the financial crisis, Brexit and domestic politics etc.

Note: The opinion polls referred to in this article are not exhaustive and mainly refer to national Gallup polls, which have often been made with the support of other pollsters.

Icelanders divided over EU in the 1980s and 1990s

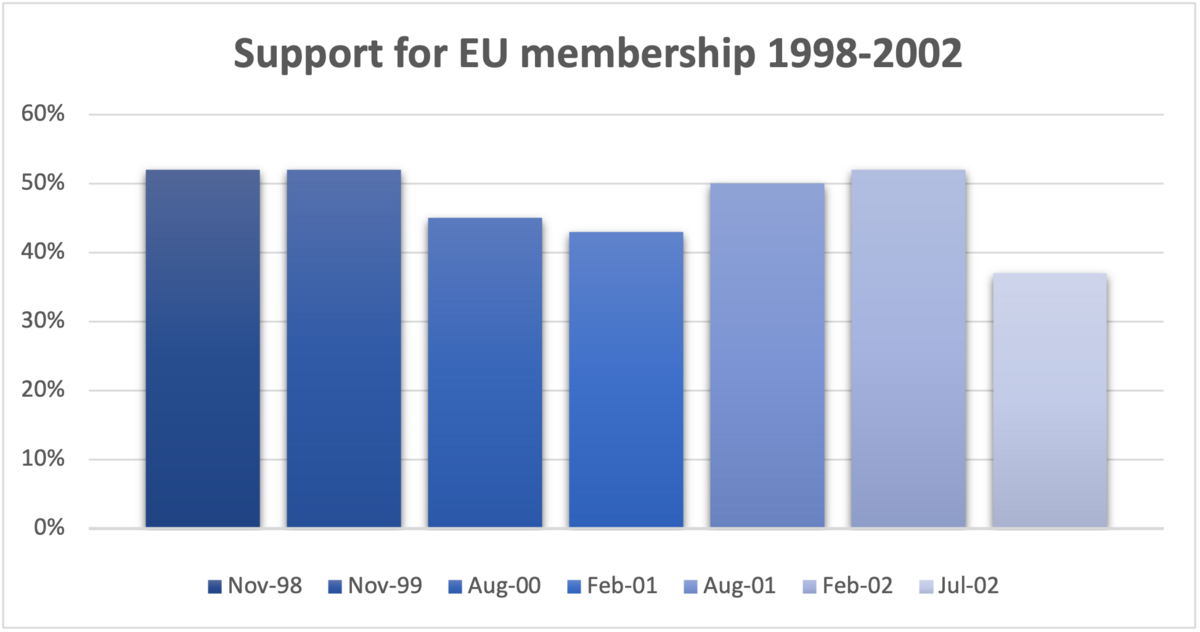

In the late 1980s and most of the 1990s, opinion polls indicated that Icelanders were quite divided about whether the nation should become a member of the European Union. The nation was split roughly into thirds between those against membership, those for, and those who were uncertain. In the late 1990s, however, support for the European Union grew and was 52% at the turn of the century. Support stayed around 50% for the first two years of the new century, but has been in decline since then.

At this time, the main arguments in favour of admission, according to the opinion polls, were to do with business and the economy, including that it would be beneficial to Iceland if it were part of the monetary union. The two main reasons given by Icelandic people against joining the EU were that it would be unfavourable for the fishing industry, and it would be a delegation of the country’s sovereignty to a supranational authority.

While a significant percentage of the Icelandic public wanted to apply for membership at the beginning of the 21st century, most political parties did not. Out of the five parties represented in the Icelandic parliament (Alþingi) after the 2003 and 2007 parliamentary elections, there was only one that supported joining the European Union: the Social Democratic Alliance (Samfylkingin (SDA)). After the 2007 election, the SDA and the Independence Party (Sjálfstæðisflokkurinn) formed a majority coalition government. Even though the pro-EU SDA was now a member of the coalition government, the political agreement made by the two parties before forming the new government did not stipulate that Iceland would seek to join the EU. It did mention, however, that the government’s stance towards the EU would be based on a report from 2004, itself rather inconclusive, which was put together by a committee on European matters arranged by the Prime Minister’s Office. In short, there appeared to be no clear signs that the government at that time would embark on a journey towards EU membership.

The Icelandic financial crisis and its impact on support for the EU

Just over a year later, Iceland was hit by a severe financial crisis. A major economic and political event, the crisis involved the defaulting of all three of the country's major, privately-owned commercial banks after they experienced difficulties in refinancing their short-term debt and there was a run on deposits in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Relative to the size of its economy, Iceland's systemic banking collapse was the largest experienced by any country in economic history. The crisis led to a severe economic depression from 2008 to 2010 and significant political unrest.

Public support for joining the EU fell drastically after the financial crisis. The political landscape also changed significantly and, in the spring of 2009, Iceland was forced to hold a snap election. This was the first time since 1927 that the Independence Party (founded in 1929) did not receive most of the votes in a parliamentary election. The Social Democratic Alliance received most support with 29.79% of the votes, and it formed a majority government with the Left-Green Movement (Vinstrihreyfingin – grænt framboð), which had received the third largest number of votes (LGM 21.68%, after the Independence Party at 23.7%).

The two new government coalition parties did not agree on applying for admission to the European Union; the Social Democratic Alliance were for and the majority of the Left-Green Movement against, believing that Iceland’s interests were better served outside the Union (see for instance its manifesto at the time). Despite these differing views, a parliamentary resolution was passed in July 2009 that negotiations with the European Union about the country’s admission would begin. The resolution was only marginally approved, with 33 parliament members voting for and 28 against, with two abstentions. For the first time, an application for EU membership - or to start the negotiations at least - had received a majority in the Icelandic Parliament.

There was some dispute over whether a referendum on the matter should take place before negotiations started, even though it was clear that a referendum would ultimately have to be held on any negotiated accession agreement before a final decision was made. Furthermore, the SDA was the only party more or less unanimously in favour of membership, while most Left-Greens were sceptical or opposed. These two governing parties ultimately reached a compromise that, while a membership application would be submitted, the Left-Greens reserved the right to oppose the outcome of the negotiations.

People and politicians out of sync?

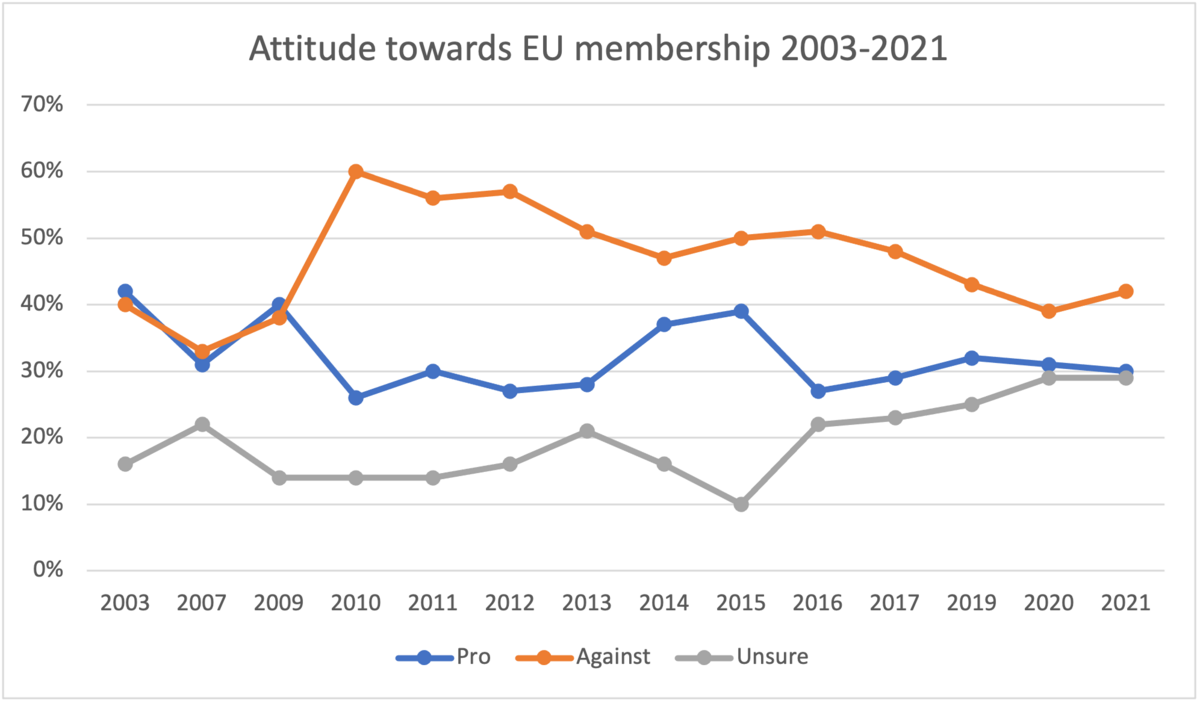

In the midst of the financial crisis, the parliament had gone from being quite opposed to the idea of Iceland’s application for EU membership to being quite positive about the idea. The public, however, seemed to react completely differently: Opinion polls in the years prior to the crisis had shown a majority in favour of applying for EU membership, but the crash saw a strong reversal of this trend. It is very likely that the Icesave affair was at least partially to blame for this. The Icesave affair was a diplomatic dispute between Iceland, the UK and the Netherlands that had begun after the privately-owned Icelandic bank Landsbanki was placed in receivership on 7th October 2008. As Landsbanki was one of the three systemically important financial institutions in Iceland to go bankrupt within a few days, the Icelandic Depositors' and Investors' Guarantee Fund (Tryggingarsjóður) had no remaining funds to make good on deposit guarantees to foreign Landsbanki depositors who held savings in the Icesave branch of the bank. Trust in the two EU member states involved in the dispute, the UK and the Netherlands, was subsequently very low in Iceland at the time and this in all likelihood had an impact on the popularity of the EU.

EU negotiations in 2010s

Opposition against EU membership reached its height in Iceland in 2010 when 60% of the nation were against Iceland’s admission. The negotiations with the EU continued despite this opposition. Trust in the Icelandic Parliament plummeted after the financial crisis - and has still not recovered to this day - which is likely to have had an effect on people’s support for the EU generally. From 2010 until the following parliamentary elections in 2013, opposition decreased slightly. In the 2013 elections, a new majority government was formed between Iceland’s two oldest parties, the Progressive Party and the Independence Party. The new majority government put the negotiations with the EU on hold and in 2015 the government stopped them altogether.

EU no longer a hot topic in Iceland?

The abrupt end to the negotiations with the EU was very controversial and much talked about in Iceland, especially because there was no discussion or debate in parliament; the government took a unilateral decision to end them. Both the decision to stop the negotiations altogether and to put them on hold, could be the reason for the sudden growth in support for Iceland’s admission to the EU in 2014 and 2015. However, that support did not last very long as support for admission decreased thereafter from 2015 to 2016, whilst indecisiveness grew. The sudden drop in support for admission in 2016 could also have been caused by the Brexit referendum which took place the same year in June. The uncertainty that Brexit brought to the EU debate generally seems also to have influenced Icelanders as the ‘undecided’ group grew at this time.

Since Brexit, support for admission to the EU in Iceland has increased slightly and, more generally in the last decade, opposition to EU membership has been slowly decreasing. The ‘uncertain’ group has also been growing in recent years and it seems that the nation has reverted back to the attitude that it had towards admission in the 1980s and early 1990s, namely, roughly a third supporting membership, a third against and a third uncertain.

In the last few years, the dust has settled on the EU discussion in Iceland and the issue seems less immediate and central than it once was. Whether this is because the public feels that the question is irrelevant today or that people are tired of the topic is difficult to say. Even though pro-EU politicians have tried to ignite the discussion again, it has not come close to reaching the prominence it had during the financial crisis.

Further reading:

- Gunnar Helgi Kristinsson and Ólafur Th. Hardarson (current authors), 'Political Data Yearbook for Iceland', European Journal of Political Data Research, 1992-2019.

- Emily D. Goodeve, 'Iceland and the European Union: An In-Depth Analysis of One of Iceland's Most Controversial Debates', Scandinavian Studies, 77, 1, 2005 (Spring) pp. 85–104.