Imagining Nordicity in the American political discourse

The Nordic region is frequently presented in the American media as prosperous and business-friendly, as well as allowing for extensive welfare benefits. US media coverage often positions one or more of the Nordic countries between the monolithic and highly politicized understandings of ‘socialism’ and ‘capitalism’ – with the many shades of mixed economies that coexist within the Western liberal and democratic sphere unacknowledged. In this way, the Nordic countries often function in the American political imaginary as blank screens upon which politicians and pundits project justifications for their own version of American economic policy—either for or against a social welfare state. The resulting images of the Nordics in the US reveal less about the complexities of the region itself, and more about current American national anxieties and the enduring legacy of the Cold War upon American self-definitions.

These days, references to the Nordic countries seem to be a constant fixture of American political news. The most visible country is Sweden, whose hands-off approach to the Covid-19 pandemic has drawn a lot of favorable attention in conservative American circles. At the end of August, Sweden was even openly praised by Scott Atlas, President Trump’s latest coronavirus-advisor, who wants the Trump administration to replicate the Swedish model, touted as an ideal strategy for the US because it favors individual and economic freedom over government-mandated restrictions.

Before 2020, references to a Nordic economic and social model appeared mostly in contexts linked to social welfare, competing economic models, and the role of the government in the economy. Mentions of the Nordic countries—usually exemplified in the US by Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, with sometimes the addition of Iceland and Finland— tend to increase during presidential election campaigns, and during times of proposed changes to the economic arrangements of the country, such as the acrimonious Obama-era debates over the US health-care system.

The significance of Nordicity in American political culture can be better understood when located within the larger national conversation about the meaning of Americanness and its reliance upon a monolithic understanding of capitalism and of socialism respectively. In this context, ‘Nordicity’ becomes a handy tool in the ideological arsenal of political pundits on the left and on the right, and it is used to illustrate radically divergent economic arrangements which Americans are encouraged to either support or reject.

PICTURE: What is Americanness? And why are discussions about it so often predicated on monolithic understandings of capitalism and socialism? Photo: colourbox.dk.

When writers on both sides of the political spectrum engage rhetorically with a ‘Nordic’ or ‘Scandinavian’ model, consistently associated to a robust social safety net, they assume that their respective readers will decode both terms as compatible with an array of other meanings: ‘democratic,’ ‘participatory,’ ‘free,’ ’happy,’ ‘egalitarian,’ as well as ‘capitalist,’ ‘innovative,’ and ‘market-friendly.’

This malleability of the terms as cultural signifiers in the current American ideological landscape is due to the often neutral position that the region occupies on the US imaginary spectrum of otherness: solidly Western and democratic, a low-conflict zone in what used to be a highly polarized part of the world, and a group of countries where the free-market economy coexists with a strong welfare system in a harmonious and productive relationship.

The latest upsurge in US interest in The Nordic Model

The latest upsurge in interest in the Nordic or ‘Scandinavian’ model started around six years ago, in response to the growing interest in democratic socialism in certain segments of the American voting population. The Democratic Socialist party has existed in the US since the 1980s, but it has been a minuscule political player on a stage almost exclusively dominated by the Democratic and Republican parties. The term was brought into the limelight in 2015 and again in 2019 by the meteoric run for presidency of Vermont senator Bernie Sanders (a Democratic Socialist who caucuses with the Democrats), who is surprisingly popular with young voters. Although Sanders’ millennial supporters seem less wedded to the ideological orthodoxies of the Cold War, repeated public opinion polls by the nonpartisan Pew Research Center show that ‘socialism’ continues to be viewed negatively—even downright unamerican—by over half of the population.

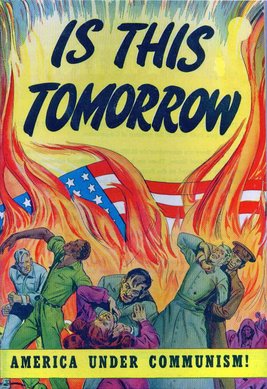

PICTURE: Cover of the 1947 propaganda comic book "Is This Tomorrow". Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

American Studies scholar Donald Pease locates the origins of contemporary American Exceptionalism in the ideological struggle of the Cold War. He describes Exceptionalism as a discourse dependent upon the historical trajectories that it attributed to Europe, the Soviet Union, and the Third World. It predicated America’s uniqueness on its alleged distinctions from Europe as a whole: no class tensions, no feudal structures, no inequality. As such, the US was believed to be inherently immune to the lures of Marxism and socialism, unlike Europe. The Exceptionalist mythology seemed validated by the abundance of the post-World War II American economy; the anti-communist propaganda of the age presented socialism as the first step towards communism and the elimination of private property, linking capitalism to American identity, upward mobility, and the country’s Exceptionalist mission globally. The economic boom under Reagan’s neoliberal leadership in the 1980s strengthened the parallel between economic freedom and political freedom, which was cemented by the collapse of the Soviet Union and ‘the end of history’ that it supposedly hailed, with the US in a new role as sole and unchallenged global superpower.

Yet history did not end in 1991, pace Fukuyama. American Exceptionalism is currently being challenged by the new geopolitical realities of the twenty-first century and by the impact of a globalized economy that has left large swaths of the US population behind. The country is experiencing levels of wealth inequality comparable to those reached during the Gilded Age, intense domestic social divisions, a dropping life expectancy, and a shrinking middle class. Politically, its democratic institutions are under assault and enjoy records low of public trust (see in The Economist's Democratic Index 2019).

Culturally, the US is deeply divided over what Exceptionalism means anymore for a social contract that is fraying. The United Nations World Happiness Report, released every year for the past decade, ranks the Nordic countries consistently at the top, with the US hovering around 19. It is not only in its pursuit of happiness that America is lagging behind other countries; according to the latest Social Progress Index (SPI) report released in September 2020, which measures the extent to which nations are able to provide for the basic human needs of their citizens, the quality of life in the US has continued to decline since 2011. The US sits at number 28 of the 163 countries included in the study, towards the bottom of the second tier; Norway is at the top of the 2020 edition, followed by Denmark, Finland, New Zealand and Sweden. In short, the Nordic countries are consistently present in the American media as examples of prosperous and business-friendly nations from a part of the world that managed to keep its capitalism humane through governmental programs that provide extensive welfare benefits.

However, whenever national debates turn to whether policies found in the Nordic countries could or should be implemented in the United States, they cease to be examples of regional exoticism and become indexes of ideological otherness.

The most prominent political narratives where examples of the Nordic countries are employed are as follows:

-

“The Nordic countries are democratic, not communist.”

Bernie Sanders and other prominent Progressive Democrats, such as Congresswoman Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, routinely turn to the Scandinavian model to critique the American unfettered capitalism, and to illustrate what their proposed socially-progressive economic policies would look like, if the American voters could be persuaded to support them. Norway, Sweden, Finland and Denmark are the preferred illustration of a form of democratic socialism intended to be decoded as non-threatening by mainstream audiences; collectively or individually, these countries represent for the American left the counterparts of Venezuela, Cuba, Nicaragua, or the Soviet Union, which are the favorite conservative examples of failed socialist experiments.

PICTURE: Bernie Sanders at a rally for the 2020 presidential election. John Nicksic, Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Sanders and Ocasio-Cortez emphasize the democratic credentials and consensual democracy that characterizes the Nordic model, and highlight the positive impact of a robust welfare state on the quality of life of their citizens. The Progressive use of the Nordic model points out the relative egalitarianism of these societies, contrasting it to the rampant inequality in the US (see this article in the New Yorker). This discussion of the region tends to leave out the realities of the free-market economies of the Scandinavian countries, the tax reforms that happened over the past two decades, and the internal diversity of the region (the growth in inequality in Sweden since the 1980s has been the largest among the OCED countries).

In short, from the vantage point of Progressive Democrats and of Democratic Socialists, the Nordic countries are primarily signifiers of societies that promote economic justice and equality within the framework of democratic institutions, and where big government programs, rather than infringing on personal freedoms, help individuals to successfully mitigate the negative impact of global capitalism on their lives.

| Differences between American & European 'liberalism' |

|---|

| Overall, the American political spectrum skews much more to the right, by comparison to the European political spectrum. Both the ‘left’ and the ‘right’ (i.e the Democratic Party and the Republican Party) support the idea of the free market and of capitalism. However, the two parties differ significantly in their positions on the involvement of the government in the economy. American liberals (the Democrats) believe the legitimate role of the government includes addressing economic as well as social issues such as poverty, health care, and education. By contrast, American conservatives (the Republicans) although rooting their ideas in classical liberalism, primarily emphasize individual responsibility and economic freedom via an unfettered free-market capitalism. Since 2008 there has been an increasing polarization in both parties. (Read how the factions within the two main parties today translate in a European context, see this article on Deutsche Welle). |

Interestingly, moderate Democrats like Hillary Clinton in 2016 or Joe Biden in 2020 consistently stay clear of Scandinavian or Nordic comparisons. Most other references to the Nordic region in American political discourse fall under the category of pro-market rebukes to the Progressive narrative. They occur most often in the publications produced by conservative-leaning think-tanks or by the many market-oriented public advocacy organizations that dominate the American public sphere, such as the Heritage Foundation, the Cato Institute, the American Enterprise Institute, or the Foundation for Economic Freedom. However, mainstream media outlets—whether they have a business focus or not—such as Forbes, Business Week, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Newsweek, Bloomberg News or the New York Times, also routinely publish op-eds that engage with the Nordic countries along similar rhetoric lines, and that rely on the same two ideologically-laden labels.

These rebukes provide variations on the following themes:

-

“The Nordic countries are not really socialist.”

One rhetorical strategy is to argue that the Nordic countries are not really socialist. By implication, the Progressive use of the region as an illustration of what democratic socialism could mean in the US is misleading. Scandinavian socialism, democratic as it may be, is described as merely a myth. To support their position, the authors focus on the free-market credentials of the Nordic and/or Scandinavian countries, the vibrant presence on global markets of Swedish, Danish, or Finnish corporations—from Lego to Nokia—and the success and creativity of their entrepreneurial sector as evidence of the capitalist credentials of the region as a whole.

Using mostly Sweden as their reference, the articles that fall in this category point out that some of the Nordic countries have free-market policies that would never pass muster in America: no minimum wage decided by the government, low corporate taxes, school choice, and no taxes on property, gifts, and inheritance. Such pieces usually play down or do not mention at all the social welfare systems in the region or the data on the high levels of life satisfaction and upward mobility of the Nordic population. The underlying assumption is that any social welfare programs or government intervention in the economy will lead to socialism, then communism and totalitarianism; since the Nordic countries are neither communist, nor totalitarian, they are not really socialist either.

-

“Socialism never works; the Nordic countries are abandoning it already.”

This line of argument builds upon the previous assumption that equates social welfare programs with socialism, leading to limitations on personal freedom, and ultimately to failed societies. The implied reader of this type of article is an idealized upper middle-class American voter concerned about increasing taxes above anything else. The articles that fall into this category tend to focus on the economic and policy changes that have taken place in the Nordic countries since the end of the Cold War. These changes are explained to American readers as evidence of the unmitigated Scandinavian embrace of neoliberal economic models due to the population’s disenchantment with socialism and the welfare state.

This paradigm is often illustrated by the de-regulatory policies implemented in Sweden in the 1990s and early 2000s. Stories that fall in this category consistently highlight the quite significant tax burden that the middle class in the region have to bear, compared to the comparatively low taxation in the US; indeed, the tax on personal income in Denmark is often the highest in the OECD, and taxes on labor and wages are also high across the region. At the same time, the stories consistently play down the strong support that the social welfare system funded by these taxes continues to enjoy among the Nordic population. Also left out are the vast differences between the US and the Scandinavian countries in attitudes towards the government; Americans have been historically skeptical of their governments, with 2019 rates of trust at a historic low of 17%; by contrast, according to the World Happiness Report, in Nordic countries, people are more willing to pay taxes for the common good also because of the high levels of social trust that citizens feel towards each other and towards their governments.

-

“The success of the Nordic countries is not due to socialism, but rather to culture; it cannot be replicated.”

This argumentative line acknowledges both the egalitarianism and the affluence of Nordic societies, but concludes that the region attained success despite, rather than because of, their generous welfare models. Their success was due to specifically cultural and geographic peculiarities, their compact size, a peculiar work ethic and collectivist impulses. Scandinavian countries are imagined as overwhelmingly homogeneous—ethnically, racially, and culturally. This emphasis on homogeneity also implies that in Nordic societies citizens are animated by a strong sense of national solidarity, and are willing to share the burden of heavy taxation for the collective good of society. Thus, the Nordic model would not be replicable because America’s strong individualism, high immigration rates, as well as its size and internal diversity—regional, ethnic, as well as racial—make national solidarity impossible. These articles rely on a fairly anachronistic image of the Nordic countries, which leaves out the significant changes in immigration rates in the region over the past years, and the impact of these demographic changes on social policies and economic arrangements; these days, the populations of the Nordic countries are quite heterogeneous, and some 19% of people currently living in Sweden were born abroad.

The use of the Nordic countries for a wide spectrum of political arguments

In conclusion, the Nordic or Scandinavian countries—or variations of their different ‘models’—function in the American political imaginary as floating signifiers, blank screens upon which politicians and pundits project justifications for why their own version of the American dream should embrace a particular economic trajectory—either towards or away from a social welfare state. Although the articles and stories that circulate in the media start from real facts and data to describe the region, they interpret them within the limited ideological space of a Manichean choice between monolithic and highly politicized understandings of ‘socialism’ and ‘capitalism,’ without acknowledging the realities of the many shades of mixed economies that coexist within the Western liberal and democratic sphere. The resulting image of the Nordics reveals less about the complexities of the region itself, and more about current American national anxieties and the enduring legacy of the Cold War upon American self-definitions.

Further reading:

- Donald Pease: The New American Exceptionalism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009).

- Francis Fukuyama. The End of History and the Last Man (New York: Free Press, 2006 (1992)).

- Joanne Sharp. Condensing the Cold War: Reader’s Digest and American Identity (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003).

- Thomas Picketty. Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Harvard University Press, 2013).

Links:

- Jefferson Chase's article on 'German and American political parties' on Deutsche Welle

- Pew Research Center Reports on American perceptions of socialism 2019

- Pew Research Center Reports on American perceptions of socialism 2011

- Pew Research Center Report: Public Trust in Government: 1958-2019

- The 2020 Social Progress Index Report

- World Happiness Report: “The Nordic Exceptionalism: What Explains Why the Nordic Countries Are Constantly Among the Happiest in the World”