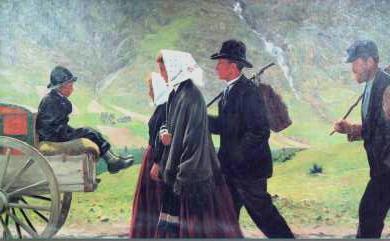

Population movement to and within Norway, 1830-1914

From the 1830s to the 1920s about 800,000 Norwegians emigrated, mostly to America. There is less general awareness of the fact that between 100,000 and 200,000 people immigrated to Norway during the second half of the 19th century. The migrants came largely from Sweden, but also from other parts of Europe. Moreover, the population was on the move within the country's borders - between regions, counties and municipalities.

A time to move

In the second half of the 19th century, migration was an increasingly important feature of Norwegian society. It was largely economic development that caused the movement. As a result of industrialisation and mechanisation in agriculture, there were fewer opportunities in the countryside for employment and far more in the city and overseas.

There were also other factors: The state implemented a liberalisation policy that facilitated migration. Compulsory service (tjenestetvangen), the duty of those who did not own property to work, was officially stopped in 1854, although the tradition of changing work place each spring and autumn continued. The passport requirement (passtvangen) was discontinued in 1860, so passports were no longer needed to travel domestically and abroad. This simplified both immigration and emigration. It was only during World War I that the need for passports was reinstated.

Immigrants from Sweden

The vast majority of immigrants were Swedes with over 100,000 relocating to Norway in the second half of the 19th century. Of the 65,000 foreign-born people in Norway in the 1900 census, three quarters were Swedish. Other large immigrant groups were Danes, Finns, Germans, Britons and Russian Jews. However, none of these groups accounted for more than 4,000 people in the 1900 census. Many other countries were represented by smaller groups. Most immigrants settled in the cities. Only Swedes and Finns settled to some degree in the countryside, the Swedes south east of Oslo and along the border to Sweden, and the Finns in the north.

Work along national lines

The majority of Swedes worked as craftsmen or workers, ending up in industry or became servants. The same was true of the Finns, but they worked as settlers and miners.

Germans and Danes found their way into commerce, crafts and – particularly the Germans – into industry. The British were often specialised industrial workers, Jews from the Russian empire were traders and industrial workers, the Swiss, livestock specialists and pastry makers, and the Italians, tunnel workers and stucco workers. Several Poles became photographers.

PICTURE: A large crowd at the ship "Montebello", which brought Norwegians to America. Photo: Wilse, Anders Beer / Norsk Folkemuseum.

Integration and assimilation

Most immigrants were easily integrated, and even assimilated into Norwegian society: The Swedes because their language and culture were so close to that of the Norwegians, and others because learning the language was a necessity.

Jewish people were able to retain their faith and the customs attached to it, but were otherwise well integrated. Finns, who were called 'Kven' (kvener) in Norway, often spent a long time acquiring the Norwegian language, but became more integrated over time.

Some maintained their Catholic faith through the establishment of their own congregations. Several immigrant groups organised themselves along religious or cultural lines without clashing with Norwegian customs. In some places they dominated districts and parts of towns, such as in the ‘Swedish town’ in Halden and ‘Kvenby’ in Vadsø.

PICTURE: Kvenbyen in Vadsø, probably photographed between 1890 and 1910. Finnish immigrants were referred to as Kven in Norway. Photo: Severin Worm-Petersen / DEXTRA Photo, Teknisk museum [Norwegian Technical Museum]

Internal movement

In the 1800s and up to 1914, two large movement patterns took place within Norway’s borders. One population flow went from the countryside to the city and towns. Often, it was a matter of moving to a nearby centre, such as to Hamar from the surrounding area. The larger cities, and especially Oslo, attracted people from a wide area, and even from the whole country. It is therefore possible to talk about regional and national concentration. The new industrial centres, such as Rjukan or Odda, often attracted people from afar too.

The second type of movement took place between regions. Because Northern Norway offered free land and plenty of fish, a significant number of people moved north from overpopulated areas such as Voss, Gudbrandsdalen, Østerdalen and Trøndelag. The areas around the Oslo fjord and the southern coast also had incoming groups of people, mostly to the cities, during the heyday of shipping (1850-1880).

On the move, but conscious of place all the same

Some population movements were seasonal, such as the construction workers (the Swedish rallare) and fishermen. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, there were annual children's journeys during the summer from poor inner-city settlements in Vest-Agder to richer settlements along the Aust-Agder coast, where there was money to be made.

More than ever before, Norwegians had become a people on the move by 1914. However, peasants still often celebrated the ties to one particular locality and place.

Further reading:

- Einar Niemi, Jan Eivind Myhre and Knut Kjeldstadli, Norsk innvandringshistorie, bind 2, I nasjonalstatens tid 1814-1940 [Norwegian History of Immigration, Vol 2] (Oslo 2003).

- Brynjulv Gjerdåker, ed., På flyttefot: innanlands vandring på 1800-talet [On the move: domestic movement in the 19th century] (Oslo 1981).

- Grete Brochmann and Knut Kjeldstadli, A History of Immigation – The Case of Norway 900-2000, (Oslo, 2008).

Links:

- Thanks go to norgeshistorie.no for allowing us to translate this article. The original article can be read in Norwegian here.