Samfundssind / Community-mindedness

Danish political banner and stigma word during the COVID-19 crisis.

Summary: The Danish word "samfundssind" (community-mindedness) is emotive and often associated with the pandemic. It can be used positively or negatively, it has different connotations for different people, and the way it is used can indicate diverging political views. Analyzing how samfundssind was used on social media can help us understand what is now a rather controversial word in Denmark.

What does samfundssind mean?

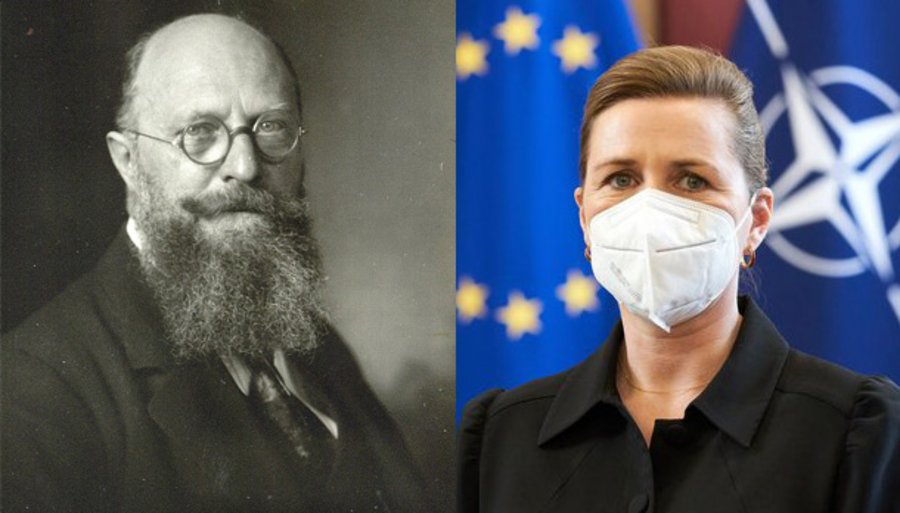

Samfundssind is a Danish word and translates roughly as ‘community- mindedness’ into English. The word experienced its first high profile appearance in 1936 when it was used by Thorvald Stauning (Danish Prime Minister 1924–1926 and 1929–1942) to urge the Danish people to show solidarity during the difficult times they faced around the time of World War II. The word has been used since then but without anyone paying particular attention to it. This situation rapidly changed when the Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen re-introduced it in her first press conference to do with COVID-19 on March 11th 2020.

The dictionary of the Danish Language Council (Sprognævn) states that ‘samfundssind’ means “to consider society’s interests higher than one’s own” (“at sætte hensynet til samfundet højere end egne interesser”).

| Community-mindedness or "samfundssind" also exists in Swedish (samhällsanda) and Norwegian (samfundssind). |

Samfundssind as a banner word

The Danish Prime Minister used this word from the start as a so-called banner word: a positive, affirmative catchphrase to indicate a group and a particular set of ideological convictions (see Hermanns’ articles from 1989 and 1994 for more on this). Political words like this set a direction and a goal, make the experience of political belonging possible and establish a willingness to act in a certain way. This, in turn, gives a necessary base for certain political endeavors. Banner words show and can even create in- and outgroups; they demand solidarity and tell the community what should be done and where their users stand. Once a banner word is established, only minimal context is necessary to activate a wide range of associations, according to Klein (1989). In our data, an overview of which is set out below, this is true for the hashtagged form #samfundssind. Indeed, it is possible to argue that the use of hashtags has become conventionalized as a means of establishing a word or formulation as a banner word.

Samfundssind as a stigma word

Mette Frederiksen’s goal with the strategic introduction of the word in 2020 was, of course, to urge the Danish population to show solidarity, more specifically to comply with the new measures that were intended to inhibit the spread of the corona infection in Denmark. It did not take long for critics of Frederiksen’s line of crisis management to pick up on this banner word and turn it into a so-called stigma word (again, coined by the German linguist Hermanns). Stigma words are used to negatively denote an opponent group, its members, goals and values. While banner words clearly indicate their user’s ideological inclination, stigma words do not automatically do so. They only indicate which groups or individuals their user opposes.

The fight over a word’s meaning

The fight for the right to define a word’s denotation (its basic meaning) and connotation (the positive or negative associations that come with it) between competing political groups is a phenomenon called meaning competition. Who wins such a semantic fight depends more on the sociopolitical context and less on linguistic cleverness or the size of a particular PR budget. Meaning competition is very often about what should be done, based on a set of values. Once a banner word becomes (or risks becoming) powerful, opposing parties will seek to ridicule and devalue it, and thereby influence the public agenda and its underlying values. Ways of delegitimizing a word include pointing to a lack of consistency between word and deed or putting quotation marks around the word (Lübbe 1967).

Samfundsind on Facebook during COVID-19

A collective research project at Aarhus University on the use of the term samfundssind in public Danish Facebook groups since the term’s re-introduction into Danish society in March 2020 was initiated in 2021. Our corpus was gathered using CrowdTangle and consists of original and shared Facebook posts containing the search word “samfundssind” from public groups from the period 11th of March 2020 to 2nd of July 2021. I manually went through the 100 posts that had received the most interactions (that is, with respect to the number of likes and other reactions, shares and comments). I looked for the use of the word in concrete contexts and classified the uses first into positive and negative mentions and then, within these two main groups, into different readings or uses. While the corpus contains a clear majority of positive uses, positive mentions show relatively little semantic variation, while the negative uses show much more variation.

There are four positive types of use for the word (author’s translations from Danish):

- Most occurrences show the same interpretation as in Mette Frederiksen’s original (re)introduction of the term as a called-for virtue, as in “Please, people, show samfundssind!”

- A little less often, but still quite frequent, is the use of samfundssind as a praiseworthy contribution, e.g., “Thank you so much for your help. This was the most beautiful samfundssind.” This type of use is very often accompanied by the hashtag #samfundssind.

- A few mentions show the reading basic contribution in the sense of “starting point for a civic society” or “the least you can expect from a good citizen”, as in “Children should not only be taught samfundssind, but also public information and education, and law and order, in one word: civic decency.”

- A last type of positive mention is meta-linguistic,: referring to the word “samfundssind” itself (rather than using it), as in Mette Frederiksen’s own Facebook post from December 18th 2020: “”Samfundssind” is the word of the year”.

Interestingly - but also logically - enough, all negative mentions are meta-linguistic (talking about the word or concept) in one way or other. This can be explained by the fact that people that mention the word negatively seek to distance themselves from the type of use as a “called-for virtue”. The use of the word samfundssind as a banner word is taken as a starting point, after which its supposedly true meaning, according to the Facebook post, is explained: it is turned into a stigma word.

People have different reasons for rejecting the word, based on different ideological stances:

- A hypocritical demand as in: “Samfundssind has been a key word during the corona crisis, but while many Danes suffer financially under the restrictive policies, the Prime Minister has got herself a pay raise.” This reading points to the divergence between word and deed.

- An unfair demand, e.g., “As an ER nurse, I have to do extra shifts, but have to pay more than two thirds of my extra pay in tax, due to Danish tax rules. My samfundssind is dwindling.”

- Among the deniers of the dangerous character of the virus, we find the reading misplaced demand: “We have an infection number of 2% of the population. The pandemic is a huge hoax. If you tell me once more that I should show samfundssind, I will slap your face.”

- A pretext for demand as in: “More and more people see through this demand for “samfundssind”. We do not buy these lies anymore.” Here, we see the use of delegitimizing quotation marks around the term.

- Citizens that refuse to wear masks for different reasons see the concept as a pretext for shaming: “This person told me to show solidarity and wear a mask – “samfundssind” 2021 means shaming!” In this example, the post explicitly redefines the meaning of the concept, and at the same time delegitimizes the word by using quotation marks.

- A misconceived concept (in the sense of “wrong interpretation”, which does not necessarily amount to a dismissal of the concept itself): “Most politicians represent a kind of samfundssind that I feel totally estranged by.”

Even language users that are not actively involved in the semantic battlefield of meaning competition cannot escape the effects of meeting the word both as banner and as stigma word in daily discourse.

Positive meanings outweighed the negative

In our study, samfundssind’s positive uses outnumbered the negative, but the negative voices seem to be louder. It seems plausible that disagreement/negativity requires an element of needing to be ’louder’ as it is demanding change of some sort rather than maintaining the status quo. Words gain their meaning in context (both linguistic, but also societal), and shifting contexts can over time change a word’s connotation or “coloring”. Neutral words can gain a negative connotation from repetitively being used in conjunction with negatively loaded words, just as much as they can obtain a highly emotive value by being combined with emotionally loaded words, also in a relatively short period of time (Karpenko-Seccombe 2021). Various linguists have used the term pragmatic strengthening for this process. And we find negatively and emotionally loaded words in our data (suffer; hoax; slap your face; lies; shaming), where samfundssind is used as a stigma word, while we also find positively and emotionally loaded words in our data (help; beautiful; decency), where samfundssind is used as a banner word. Older and newer uses of a word can co-exist, eventually leading to polysemy (the existence of two separate words with two separate meanings, as pointed out by Aaron in her article from 2010 on the word ‘lame’ in English). At this point in the word samfundssind’s development, it is not clear whether one meaning will prevail over the other, or two separate words will develop. It is possible that the importance of this word will wane in parallel with the waning of interest in the pandemic.

Linguistics can shed light on points of tension in society.

This article is published in response to an interest in Covid-19/crises, samfundssind, social cohesion, and social division.

Further reading:

- Fritz Hermanns, ‘Deontische Tautologien. Ein linguistischer Beitrag zur Interpretation des Godesberger Programms (1959) der Sozialdemokratischen Partei Deutschlands‘ [A linguistic contribution to the interpretation of the Godesberg Program (1959) of the Social Democratic Party of Germany]. In: Josef Klein, ed., Politische Semantik. Bedeutungsanalytische und sprachkritische Beiträge zur politischen Sprachverwendung [Political semantics. Contributions to the analysis of meaning and criticism of language on the political use of language]. (Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag; 1989) pp. 69-149.

- Fritz Hermanns, ‘Schlüssel-, Schlag- und Fahnenwörter. Zu Begrifflichkeit und Theorie der lexikalischen „politischen“ Semantik’ [Keywords, buzzwords and flag words. On the concept and theory of lexical “political” semantics.] in Arbeiten aus dem Sonderforschungsbereich 245 “Sprache und Situation“ [Works from the Collaborative Research Center 245 "Language and Situation"] Bericht Nr. 81 (Heidelberg/Mannheim; 1994).

- Hermann Lübbe‚ ‘Der Streit um Worte. Sprache und Politik’ [The quarrel over words. Language and Politics]. In: Hans-Georg Gadamer (ed.). Das Problem der Sprache [The problem on language]. (München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag; 1967) pp. 351-371.

- Jessi Elana Aaron, ‘An awkward Companion: Disability and the Semantic Landscape of Lame’. Journal of English Linguistics 38, I (2010) pp. 25-55.

- Josef Klein, ‘Wortschatz, Wortkampf, Wortfelder in der Politik‘ [Vocabulary, battle of words, fields of words in politics]. In: Josef Klein, ed., Politische Semantik. Bedeutungsanalytische und sprachkritische Beiträge zur politischen Sprachverwendung [Political semantics: Contributions to the analysis of meaning and criticism of language on the political use of language]. (Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag; 1989) pp. 3-50.

- Paul Hopper and Elizabeth C. Traugott, Grammaticalization (2nd ed., Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

- Paul Hopper and Elizabeth C. Traugott, ‘Grammaticalization’. Journal of Linguistics, 31(1) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993) pp. 186-188.

- Tatyana Karpenko-Seccombe, ‘Separatism: a cross-linguistic corpus-assisted study of the word meaning development in the time of conflict’. Corpora 16, 3 (2021) pp. 379-416.

Links:

- ‘How do you define “samfundssind”? – A little questionnaire study’. Blog by the author (in English and Danish).

- '”Samfundssind”: How a long-forgotten word rallied a nation’. Interview with Marianne Rathje from the Danish Language Council on BBC.com by Mark Johanson on 4th August 2020.

- Read about Thorvald Stauning on danmarkshistorien.dk (In Danish).