The age of insecurity and the Danish welfare state

Denmark and the other Nordic countries pride themselves on being safe and secure societies and there has been much talk of ‘tryghed’ by Danish politicians over the last 10 years. Still, the poorest generally feel less secure than those with larger disposable incomes, although this can be ameliorated by generous social welfare policies. However, research by a team at the University of Southern Denmark has found that the more generous welfare states do not necessarily have a smaller gap between how insecure the poor feel compared to the rest of society.

Since the global financial crisis of 2008, and certainly since the Covid-19 pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and a string of alarming updates on climate change, the future appears ever more uncertain and more threatening. It comes as no surprise then that Danish politicians have seized on this. Particularly the social democrats under Mette Frederiksen have been very keen on all these measures, but other parties sing to a similar tune. It seems like virtually every problem can be politically packaged as addressing ‘tryghed’.

What does ‘tryghed’ mean?

The Danish term ‘tryghed’ – ‘trygghet’ in Swedish and Norwegian – is a curious word, which doesn’t correspond directly to the English security-safety distinction or, for example, the German word ‘Sicherheit’. Danish (and the other Scandinavian languages) allows for a distinction between the objective ‘sikkerhed’ and subjective 'tryghed'. The word also carries distinct connotations of warmth, being cared for, and homeliness. While it is not new in politics, the politicization of ‘tryghed’ has seen a massive peak in Denmark in recent years. Security cameras or surveillance cameras have been renamed ‘tryghedskameraer’ and the police installed 300 additional ones in public spaces across the country. New local police stations, rather than being rolled out to crime ‘hot spots’ are targeting a fear of crime in small towns. Uniformed ‘tryghedsvagter’ to assist the police will now also be piloted in some municipalities. It is not all about ‘law and order’, however. Social policies such as a new early retirement scheme (dubbed the ‘Arne pension’) were introduced to make voters feel more ‘trygge’. To deal with the latest crisis, the state gives inflation help for pensioners and low-income families. It all culminated in 2022, the year of the so-called ‘tryghedsvalg’, a general election which appeared to revolve around people’s sense of security in lots of different contexts.

The feeling of insecurity has been rising in Denmark

An interdisciplinary research group at the University of Southern Denmark has been studying feelings of insecurity among people in Denmark, the Nordics and other rich countries, and initial findings suggest that we are not all equally affected by recent developments. Based on data from two separate representative surveys, TrygFonden’s Tryghedsmålinger (since 2004) and the OECD’s Risks That Matter (2020) study, we can paint a relatively precise picture of subjective insecurity for up to 25,000 individuals in 20 rich democracies. The Danish data show, first, that insecurity has indeed been rising on average, and that, in 2021, one out of five respondents stated that they ‘generally feel insecure in their everyday lives’. This is a massive increase from 2004, when the same survey showed that just 2.5% of respondents felt this way.

Unfortunately, this is difficult to compare precisely as we don’t have such a time series for the other countries, but the OECD data also covers insecurity across a wide range of separate issues, from health and crime to financial insecurity. People were asked here how concerned they were about issues like becoming ill or disabled, losing their job, not finding affordable housing or being victim of a crime. Interestingly, Denmark - despite the recent rise in insecurity - still comes out on top as the country with the least subjectively insecure population in the group.

Passengers on the ‘cheap seats’ feel much more insecure

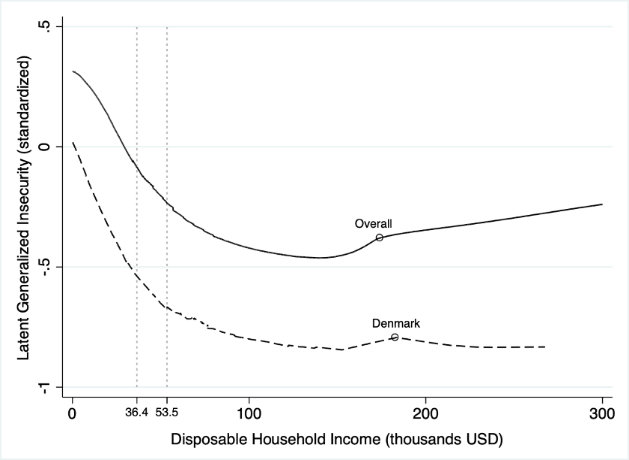

One could assume that these worries and fears from illness to crime are all very specific and that there is a multitude of profiles or ‘faces of insecurity’, but that is not what our research has found. People’s worries tend to be very closely connected. In other words, respondents who are concerned about one issue also tend to be anxious about some or all of the others. Perhaps this points to a deeper form of ‘ontological insecurity’ about the pace of change in the modern world, as suggested by the sociologists Zygmunt Bauman and Anthony Giddens already in the 1990s. Empirically, this pattern allows us to construct a synthetic measure of ‘latent insecurity’, capturing people’s underlying concern about their future more generally. And here is where we can see that we are not all in the same boat. The passengers on the ‘cheap seats’ do indeed feel much more insecure than the more comfortable middle class (see Figure 1). This security gap between the poor and the rest of the population exists in all countries studied (except for the United States where it is the rich who worry most about the future). The most vulnerable who lack the means to privately insure against multiple shocks fear the future most. Moreover, education levels and gender also have an influence, with women feeling typically less secure than men.

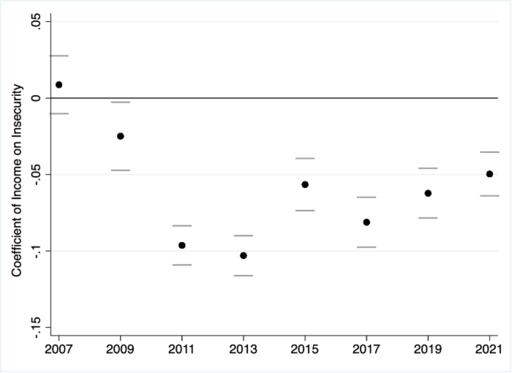

In Denmark, the gap starts to open up after the financial crisis in 2008 and has been relatively pronounced since then. Figure 2 shows the effect of income on generalized insecurity over time. While in 2007 there was effectively no systematic difference in line with income, it has become quite pronounced ever since. The gap has been so persistent that neither economic recovery nor additional shocks like the Covid-19 pandemic have been able to influence it much. While more secure on average, when it comes to inequality in security, Denmark basically looks like any other rich country now.

More generous welfare is not associated with a smaller 'security gap'

Are protective policies, especially welfare and criminal justice, adequate to address the security gap? By using statistical regression models, we can control for a variety of demographic characteristics and political context conditions – as well as for Covid-related worries, which could influence the 2020 findings. The results for 20 countries, including Denmark, show that several, but not all, kinds of welfare policies, tend to lower insecurity. More generous pensions or sickness benefits and higher spending on active measures like retraining schemes are associated with lower insecurity while others even have counterintuitive, positive effects. Spending on police, prisons and the judiciary has, surprisingly, no effect on generalized insecurity nor on worry about crime. Overall, this suggests that at least some welfare state programs make people worry less on average. When it comes to the security gap, however, the results are sobering. More generous welfare states do not display a smaller subjective insecurity gap between the poor and the rest of society. Poor people’s confidence in the welfare state being there for them in the future seems very limited.

For people at the lower end of the income scale and for those in socially marginalized areas, policies are often an ambiguous mix of support, surveillance and tougher sentencing. We know from discussions with civil society groups that many vulnerable citizens feel that these measures can lead to more - rather than less - insecurity for them.

Furthermore, the sheer multiplication of rules and changes to existing rules adds to the uncertainty about how to behave. This means that, despite all the talk, there is a mismatch between what these measures do and who needs protecting the most. New police stations in small, rural towns and new pension rights contrast with heavy-handed measures in urban areas, including more punitive welfare measures. Parents, especially in areas with many migrants, are feeling increasingly insecure about measures such as ‘parenting orders’ that allow the state to take away child benefits if their children are absent from school or commit crimes. Given the persistence of the security gap and the limitations of existing welfare policies, new ideas are needed on how those at the margins of society can regain hope in the future.

New initiatives about 'tryghed' in Denmark and elsewhere need to be adequate to address inequality in security. Of course no politician wants to appear to be against more security. Our project’s results show that people at the margins of society still feel much more insecure than others, and this should certainly not be forgotten in the way we address insecurity politically.

Further reading:

- Anthony Giddens, Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1991).

- Bethany Albertson and Shana Kushner Gadarian. Anxious Politics: Democratic Citizenship in a Threatening World. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

- Dina Hummelsheim, Helmut Hirtenlehner, Jonathan Jackson, and Dietrich Oberwittler. 2011. "Social Insecurities and Fear of Crime: A Cross-National Study on the Impact of Welfare State Policies on Crime-related Anxieties." European Sociological Review 27, 3 (2011) pp. 327-345.

- Zygmunt Bauman, Community: Seeking Safety in an Insecure World. (Cambridge: Polity, 2013).

Links:

- Security, equality and brotherhood (Tryghed, lighed og broderskab), article in Weekendavisen on 22nd October 2022.

- Core Group ‘The Politics of Insecurity’ (POINS) at SDU, financed by the Velux Foundation.

- Twitter profile of the project