The Nordics in the modern Japanese political imagination

In the early 1900s, Japanese progressive intellectuals, writers, and feminist activists questioned their country’s quest for power and looked to Scandinavia for an alternative modernity. The Scandinavian modern breakthrough peaked in Japan in the 1910s and 1920s on the back of a burgeoning interest in Nordic literature, philosophy and political thinking. Its influence weakened in the 1930s and then returned from 1945 onwards, evident in the voices of advocates for pacifism, neutrality and women’s rights. Its influence can arguably still be felt today.

Survival in the age of colonialism, Japan in late 19th century

With the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Japan turned from isolationism to international engagement and a struggle for survival in a western-dominated world. The Charter Oath declared in the name of the new monarch that:

“Knowledge shall be sought throughout the world…[which would] enrich the nation and strengthen the military.”

Since Japan could not beat the encroaching imperialist powers, its leaders chose to join them as an industrialised great power. The unpalatable alternatives were outright colonisation, or the quasi-colonial humiliation suffered by China.

Japan thus modelled itself on the great powers of the day, which is to say Britain, the United States, France, and Prussia. Britain, above all, came to occupy the place China once held as the standard for cultural, economic, and political achievement and the source of ideas and technologies. Japan industrialised, developed a modern military, and projected its power in East Asia: Korea came under Japanese control from 1876, Taiwan was colonised in 1895, and humiliating demands were issued to China. With the symbolically important victory of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, Japan had become the first non-western modern great power in a mere four decades. But not everyone rejoiced in this apparent success, and some questioned the wisdom and ethics of imperialism and militarism.

In late 1800s and early 1900s, Japanese imperialism saw the success of the Russo-Japanese war in 1905, but a growing number of intellectuals looked for an alternative, some of whom looked towards Scandinavia. Photo: A Japanese military hospital. Coloured woodcut, ca. 1904 - Europeana, Wellcome Collection (CC BY).

Scandinavia as an alternative modernity, 1880s-1920s

In the 1880s, some Japanese intellectuals, writers, and political activists began to take an interest in Scandinavia. This undercurrent grew until the mid to late 1920s, fuelled by disenchantment with the mainstream modernisation strategy and a sense that what had been accomplished was shallow and inauthentic. Their search for an alternative modernity led some to authors such as Georg Brandes, Harald Høffding, Henrik Ibsen, August Strindberg, Hans Christian Andersen, Bertel Thorvaldsen, Ellen Key, Søren Kierkegaard, and N.F.S. Grundtvig. Additionally, some found the image of Scandinavian thought, culture, art, education, gender relations and politics transmitted through German and English-language sources appealing. Nordic language skills hardly existed until the second half of the 20th century.

Mori Ōgai’s (1862-1922) translation of Andersen’s The Improvisatore (Improvisatoren) in 1888 was hence based on a "free" German translation. It had more in common with traditional East Asian prose than with Andersen’s Danish. No matter the accuracy of the translation, it became an instant classic and put Nordic literature firmly on the horizon. In 1889, the philosopher Inoue Tetsujirō (1855-1944) attended a conference in Stockholm and visited Høffding in Copenhagen. In 1892, an article on Ibsen by Brandes appeared in the literary journal Waseda Bungaku, translated by Tsubouchi Shōyō, and Ishida Shintarō’s abridged translation from German of Høffding’s Psychology (1882) (Psykologi i Omrids paa Grundlag af Erfaring) came out in 1897, followed by Philosophy of Religion (Religionsfilosofi) in 1912 and his Brief History of Modern Philosophy in 1917. Høffding’s popularity prompted Kobayashi Ichirō to write an article on “Modern Danish Philosophy” in 1911, based on German sources. In 1915, a translation from English of Brandes’ Main Currents in 19th Century Literature (Hovedstrømninger i det 19de Aarhundredes Litteratur) was published. The number of indirect translations and the interest in Scandinavia thus grew steadily after the turn of the century.

Ellen Key’s influence on Japanese feminism

By the 1910s, this burgeoning appreciation of the Scandinavian modern breakthrough set the stage for the massive influence Ellen Key (1849–1926) came to have on Japanese feminism through Hiratsuka Raichō (1886-1971) and Yamada Waka (1879-1957). Japan was first introduced to Key through Ōmura Jintarō’s partial translation of The Century of the Child (Barnets Århundrade) in 1906.

HHiratsuka Raichō (1886-1971) was a key feminist figure in Japan inspired by the Swede Ellen Key. Photo: Wikimedia Commons, By Unknown, Public Domain.

Hiratsuka was inspired by the critique of patriarchy in Ibsen’s A Doll’s House (Et dukkehjem) and by Key, whose writings she encountered in 1911 and 1912. Both were politically and intellectually minded women from elite backgrounds for whom traditional gender roles were constraining. Hiratsuka found a kindred spirit in Key, whose Renaissance of Motherhood she translated from English in 1919. Thanks to Hiratsuka and her pioneering journal, Seito (Bluestocking), Key is perhaps remembered more in Japan than in Scandinavia today as a founding mother of feminism of equal stature to Mary Wollstonecraft.

Turning Japan into “Denmark on a bigger scale”

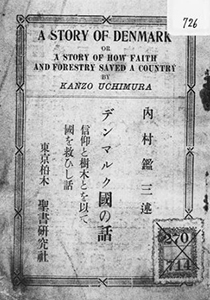

The Protestant evangelist, journalist and campaigner Uchimura Kanzō (1861-1930) met the Danish theologian Carl Skovgaard-Petersen (1866-1955) in Tokyo in July 1911. Skovgaard-Petersen described Uchimura as “a loner by nature and a bit of a Japanese Søren Kierkegaard, whom he likes to cite copiously in the journal he edits.” In October that year, Uchimura delivered the influential and curiously titled lecture A Story of Denmark: A Story of how Faith and Forestry Saved a Nation (which was subsequently produced as a pamphlet). In the following years, he continued to spread his enthusiasm for Kierkegaard, Grundtvig, and a vision of Scandinavia as a beacon of ethical politics, religious and ethnic tolerance, mass education, Protestant industriousness, and environmentalism. Uchimura profoundly influenced the next generation of liberal educators and opinion leaders. Tokai University and the International Christian University were founded on his interpretation of Grundtvig’s principles, and the political scientists Ōtsuka Hisao (1907-1996), Yanaihara Tadao (1893-1961) and Nanbara Shigeru (1889-1974) were among his pupils.

Uchimura Kanzō's 'A Story of Denmark', with the curious sub-title 'A story of how faith and forestry saved a country', inspired Japanese thinkers to reject power politics and focus on other things, such as the economy. Photo: National Diet Library Digital Collections.

A Story of Denmark told the uplifting tale of how Denmark rejected power politics after the Second Schleswig War of 1864, focused inwardly on economic development and outwardly on international trade. It portrayed Denmark as a nation that in a very short time had achieved record levels of prosperity by peaceful means despite its modest size and lack of natural resources. It recounts how Enrico Dalgas (1828-1894) – through perseverance, patriotism, and faith – reforested the Jutland heathlands and lifted the national spirit, thereby more than compensating for the loss of Schleswig and Holstein. The account is riddled with inaccuracies, but the purpose was not to teach Nordic history, it was to warn Japan’s “flippant and frivolous statesmen” that they were on the fast track to ruin. The optimistic message, however, was that defeat in war could lead to improvement in the long run. A later article by Uchimura argued that Japan should become “Denmark on a bigger scale” rather than Britain on a smaller scale.

The Nordic interlude and its aftermath

Hiratsuka, Uchimura and other early 20th century Japanese intellectuals found sources for cultural and political critique in Danish and Swedish thought and history. The peak of their influence coincided with the Taishō Democracy era from 1912 to 1926, after which it waned before returning in 1945. Post-war Japan can be considered a partial realisation of their visions of pacifism, developmentalism, toleration, prosperity, and gender equality.

Uchimura passed away in 1930, just before intensifying repression and international conflict led to 15 years of war, the firebombing of Tokyo, the nuclear annihilation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and finally surrender and occupation. Uchimura’s pamphlet went out of print, and Hiratsuka withdrew from public life while other feminists like Yosano Akiko (1878–1942) turned nationalistic and supported the war. Most of the Scandinavian-inspired reformists kept a low profile and returned as opinion leaders from 1945. With the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, Hiratsuka became a strong voice in the peace movement, arguing for pacifism and Japanese neutrality while continuing to campaign for women’s rights. Uchimura’s disciples Yanaihara and Nanbara served as presidents of the University of Tokyo and shaped the post-war order through their policy influence.

Imperial power politics had led to the very disaster Uchimura foresaw, but also the opportunity for renewal. Japan in 1945 was in the same situation as Denmark in 1864: defeated, demoralised, economically ruined, and territorially reduced to a nation state. As Uchimura believed the Danes had done, the Japanese picked themselves up by the bootstraps, renounced war, and embarked on export-led economic development. Some of what Hiratsuka campaigned for became a reality in that female suffrage was introduced and patriarchal family laws were abolished. Uchimura’s Story of Denmark embodied the values of the new Japan, emerged from obscurity to become hugely popular and a staple of the school curriculum. It is often cited by Nordic studies scholars as a catalyst for their interest in the region and it continues to inspire thinking about security, development, ecology, and energy policy after the Fukushima nuclear disaster. Scholars and commentators continue to look through a Nordic mirror to imagine a better Japan.

Further reading:

-

Christian Morimoto Hermansen, ‘Winther and Kagawa: A Commentated Translation of Denmaaku no inshou [Danish Impressions] by Kagawa Toyohiko’ Journal of Studies on Christianity and Culture (関西学院大学キリスト教と文化研究第, 2014) Vol. 15, pp. 63-90.

- Hiroko Tomida, Hiratsuka Raichō and Early Japanese Feminism (Leiden: Brill, 2003).

- Hiroko Willcock The Japanese Political Thought of Uchimura Kanzō (1861–1930): Synthesizing Bushidō, Christianity, Nationalism, and Liberalism. (Lewiston, N.Y: Edwin Mellen, 2008).

- Hiroshi Shibuya & Shin Chiba (eds.) Living for Jesus and Japan: The Social and Theological Thought of Uchimura Kanzo. Grand Rapids & Cambridge: W.B. Eerdmans, 2013).

- Masugata Kinya 桝形公也 2015 「内村鑑三 ー 日本のキェルケゴール」 [‘Uchimura Kanzō: The Kierkegaard of Japan’] Kirukegōru Kenkyū 13, May 2015, pp. 68-86

- Mirá Sonntag, ‘Uchimura Kanzô Studies and Translations in Western Languages: A Bibliography’ Japonica Humboldtiana, 4 (2000), pp. 131-178.

- Raichō Hiratsuka, In the Beginning, Woman was the Sun: The Autobiography of a Japanese Feminist. Translated, with an Introduction and Notes, by Teruko Craig (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

- Robert N. Bellah, Imagining Japan: The Japanese Tradition and its Modern Interpretation (Oakland: University of California Press, 2003).

- Uchimura Kanzō Uchimura Kanzō Zenshū. [Complete Works of Uchimura Kanzō] Vol. 15. (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1984 [1932]).

- Yanabu Kunichika, 日本的プロテスタンティズムの政治思想 [The Political Thought of Japanese Protestantism] (Tokyo: Shinkyō Shuppansha, 2016).

Links:

- Japan Association for North European Studies

- Translation of 'A Story of Denmark' by the author

- Works by Japanese women, Japan Times