The reunification of Denmark in 1920

The reunification of Southern Jutland with Denmark was made possible in 1920 with the German defeat in the First World War. It took place in June 1920 after a process that in fact started with Germany's admission of defeat in October 1918 and its ensuing request for an armistice. The reunification followed a plebiscite in the concerned areas. In Denmark, questions over reunification ignited heated political debate, as there was a widespread wish that southern parts of Schleswig should be incorporated into Danish territory as well.

*Listen to this article as a podcast in English or Danish by clicking here.

Background to the reunification

In 1864, Denmark lost the Second Schleswig War and ended up ceding the duchies of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg to Prussia (the German Empire from 1871). Southern Jutland, the original name for the Duchy of Schleswig, had been lost to Germany, and the new Danish-German border was drawn just south of Kolding. The vast majority of people in the northern part of Southern Jutland still felt Danish. Consequently, the idea of a political reunification with at least parts of Southern Jutland enjoyed significant popular support in Denmark in the second half of the 19th century. However, it was not until the German defeat in the First World War that it became politically feasible. The question over southern Jutland’s future was not subject to political discussion during the war, and when it suddenly emerged towards the war’s final stages, many were unprepared for the situation.

The potential reunification could have been based on two different principles at that time:

- A democratic principle, relating to the idea of a people's right to self-determination.

- An historical principle, where reunification could be seen as restoring a previous state of law.

According to the principle of self-determination, the country followed the people. According to the historical principle, the people would have to follow the country. Neither of these two principles was followed to the letter, but they constituted the crucial political dividing line to which the reunification issue gave rise.

The 1918 negotiations

The first official Danish position on the issue came with the adoption of a resolution at a closed meeting between the two chambers of parliament at that time Folketinget and Landstinget on 23 October 1918. The war had not yet ended, but the impeding German defeat was obvious to everyone. The resolution stated that Rigsdagen (the Danish Parliament) wanted the issue resolved in accordance with the concept of popular self-determination, i.e. through a democratic solution.

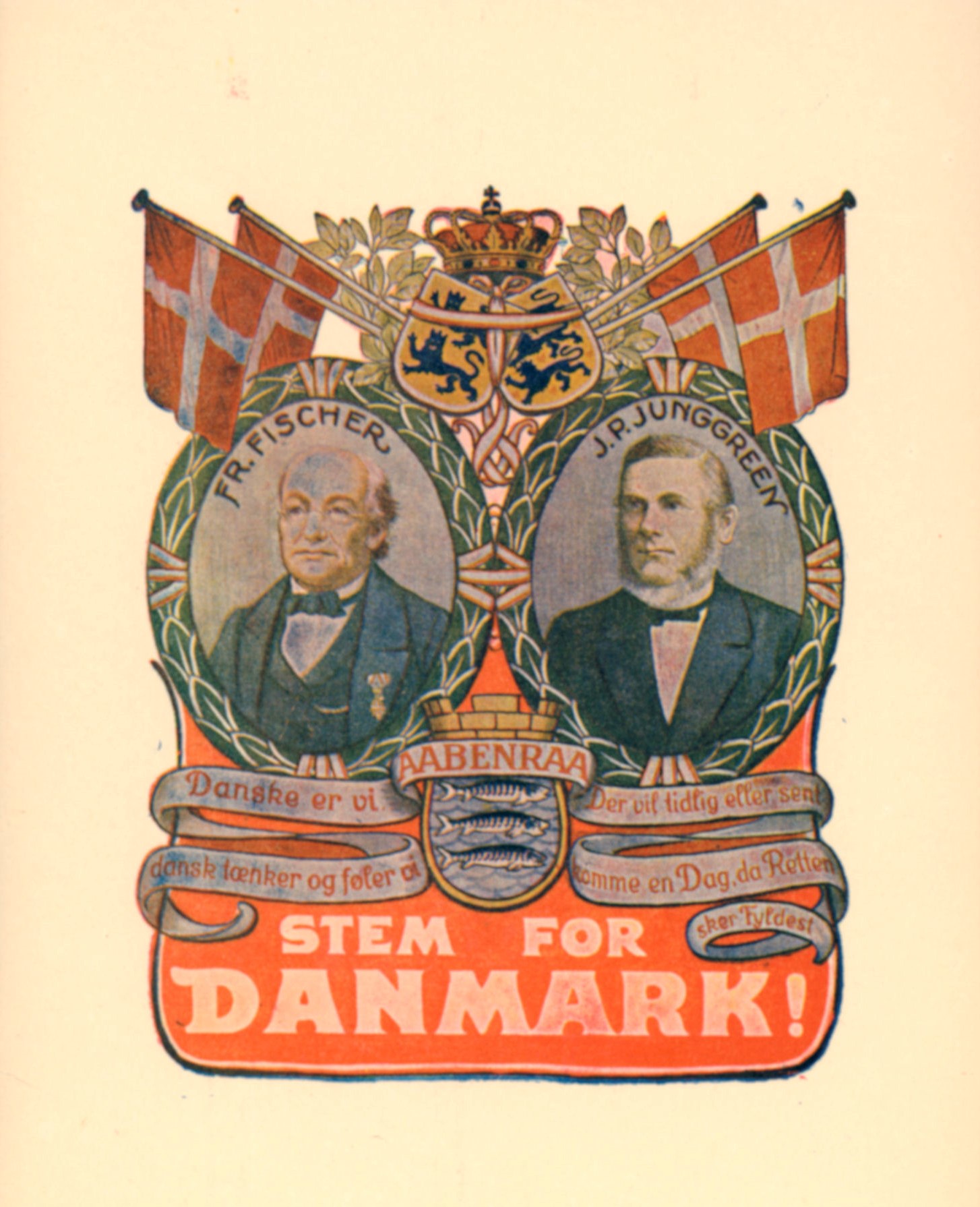

In 1918, H. P. Hanssen was the political leader of the Danes living in Southern Jutland. He raised the question in the German Reichstag on 23 October, imploring the German government to resolve the issue at the ensuing peace settlement. On 14 November, after the armistice, the acting German Foreign Minister gave a written undertaking setting out that Germany was prepared to resolve the issue at the forthcoming peace conference. With the German Foreign Minister’s announced commitment, Danes in Southern Jutland, German territory at the time, were able to freely discuss the issue. On 17 November, delegates from the Electoral Association in Northern Schleswig (Den Nordslesvigske Vælgerforenings Tilsynsråd), the supreme political body for Danish-minded people in Southern Jutland, adopted the so-called Aabenraa Resolution, which set out their requests for the reunification scheme.

PICTURE: Henrich Dohm's 'Genforeningen den 10. juli 1920'. King Christian X crossing the former border between Denmark and Germany, symbolically marking Southern Jutland's reunification with Denmark.

The resolution pursued a reunion based on a unified plebiscite in North Schleswig, defined as the area between the border from 1864 and the so-called ‘Clausen Line’ (almost identical to the final border). The area was regarded as one constituency, meaning that the final decision should be based on the overall result regardless of the results in each smaller voting district. The resolution also stated that additional plebiscites could be held in individual districts south of the border, if it was requested.

H. P. Hanssen forwarded both the Aabenraa Resolution and the German Foreign Minister’s undertaking of 14 November to the Danish Government, while asking it to present the question of Southern Jutland at the forthcoming Peace Conference. Danish Foreign Minister Erik Scavenius preferred the issue to be resolved by a direct Danish-German agreement, but capitulated, and the question was thereafter presented to the Allies, who agreed to deal with it at the upcoming Peace Conference in Paris.

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 1864 | Denmark loses the Second-Schleswig War and cedes Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenborg to Prussia. |

| October 1918 | With the German defeat in the Second World War imminent, a closed meeting takes place in the Danish parliament to determine the country's position on the Reunification question. |

| November 1918 | The supreme political body for Danes in Northern Schleswig adopts the Aabenraa Resolution, setting out their request for the reunification scheme. |

| January 1919 - June 1919 | The Versailles Peace Conference takes place in Paris. The Versailles Treaty is signed on June 28. |

| February 1920 | The plebiscite in Zone 1 (Northern Schleswig) produces an overwhelming Danish majority (75%). |

| March 1920 | The plebiscite in the Zone 2 (including Flensburg) results in a strong German majority (80%). |

The peace conference at Versailles

The Versailles Peace Conference lasted from January to June 1919. It was organised in such a way that both official and unofficial delegations were welcome. A private Danish group called the Dannevirke Movement (Dannevirkebevægelsen), who wanted the future border to extend further south, decided to exploit this opportunity. The Dannevirke Movement did not just want to extend the border further than the Danish Government; they wanted to do so regardless of what people in the affected areas wanted. There was little space for the principle of self-determination in this vision.

The Dannevirke Movement was supported actively by French diplomacy, which aimed to weaken a new Germany as much as possible. The Dannevirke Movement was therefore given the opportunity to submit a memorandum to the Conference, which was dealt with on a par with Denmark’s official request.

The French officials charged with the practical work at the peace conference designed the peace proposal in such a way that it not only suggested a comprehensive plebiscite in Northern Schleswig (Zone 1) and a separate, district-based vote in Middle Schleswig (second zone), but also a third district-based vote in a third zone that covered the area between the second zone’s southern border and a line from Schleswig to Tønning. The latter went far beyond what had been officially proposed by Danish officials. The Danish government suggested protesting against the proposal as it had no interest in absorbing areas with a German majority into Denmark; it was expected that many Germans would vote to belong to Denmark due to Germany’s impoverished situation at the time.

Up until this point, there had been a widespread political consensus in Denmark over how to approach the Peace Conference. However, the Social Liberal government’s desire to protest against the peace proposal caused this to collapse, as the Conservative Party refused to support the protest.

Nevertheless, the government and the Liberal Party managed to agree on a modestly worded declaration stating that a vote in the third zone would not be in Danish interests. Together with pressure from British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, who was eager to give minor concessions to Germany, this ensured that the provision for a third zone was not included in the final peace treaty meaning that this area would have no choice but to remain a part of Germany.

Map showing distribution of the German vote in the plebiscites of 1920. The pink shading indicates a greater percentage of the vote was for Germany and the blue shading for Denmark. Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

After Versailles

The Versailles Treaty was signed on 28 June 1919, but did not enter into force until January 1920. In the meantime, the question of Southern Jutland had turned into a crucial point of conflict in Denmark. The controversy revolved around Flensburg, Schleswig’s largest city, located in the northern part of the second zone. It was expected that the imminent vote would reveal a German majority in Flensburg, but the possibility of a large Danish minority in the city was mentioned so often that for some it almost became a certainty.

When the Versailles Peace Treaty finally entered into force, the plebiscite in the first zone, Northern Schleswig, was planned for 10 February. The plebiscite in the second zone, Middle Schleswig including Flensburg, was planned for 14 March. As had been expected, the vote in Northern Schleswig produced a strong Danish majority of approximately 75%, with only a few minor districts voting in favour of Germany. The vote in the second zone revealed an even stronger majority, but in favour of Germany with approximately 80% of the votes. Although the vote in the second zone was divided into smaller districts, none of them produced a Danish majority.

In the town of Flensburg, around 25% of the vote share was Danish. That was a significant improvement on the last election prior to the First World War, but lower than what most had expected. In Denmark, there was still a strong urge to do something for Flensburg, but the radical (Liberal) government wanted to follow the voting result and rejected any further action. This conflict was of major importance to what is called 'the Easter Crisis' that developed in the spring of 1920, when King Christian X, who also strongly supported Denmark taking over territory in the second zone, ended up deposing the democratically-elected Danish government under Zahle who disagreed.

Those who were dissatisfied with the extent of the reunification threw their efforts into achieving internationalisation of the second zone, that is, they wanted a solution similar to either the Saar region or Danzig where the area was overseen by the League of Nations. Yet, there was no foundation for the idea of internationalisation in this way in the peace treaty and the idea was swiftly rejected by the British. After being recommended by the International Commission that had been administering the two zones since 1920, the border was settled at the boundary between the first and second zones. From 15 June 1920, Southern Jutland was under Danish sovereignty, and on 10 and 11 July 1920, the reunification was officially marked by King Christian X’s famous entry on horseback in Southern Jutland. There was also a large popular gathering at Dybbøl Banke, the site of the Danish defeat to Prussia in the Second Schleswig War of 1864.

The popular celebrations at Dybbøl Skanse in Southern Jutland on 11 July, 1920. About 50000 people participated in the event, which was also overseen by King Christian X. During the celebrations, King Christian was given an old Danish flag by Hans Thomsen, a 85-year old veteran from the Danish-Prussian War of 1864. This silent film of the popular celebrations on 11th July 1920 is from danmarkpaafilm.dk, Filmcentralen.dk/Det Danske Filminstitut.

Further reading:

-

Hans Schultz Hansen, Genforeningen, 100 danmarkshistorier [The Reunification] (Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2019).

-

Simon Kratholm Ankjærgaard (with Ole Sønnichsen), Genforeningen 1920. Da Danmark blev samlet [The Reunification 1920. When Denmark was reunified] (Copenhagen: Storyhouse, 2019).

-

Troels Fink, Da Sønderjylland blev delt 1918-1920 [When Southern Denmark was divided] (Aabenraa: Institut for Grænseregionsforskning, 1979).

Links:

-

Read about the Easter crisis on danmarkshistorien.dk (in Danish).

-

Thanks go to danmarkshistorien.dk for allowing us to translate this article. Read this article in Danish on danmarkshistorien.dk.