Valkyries and Danish national symbolism in the 19th century

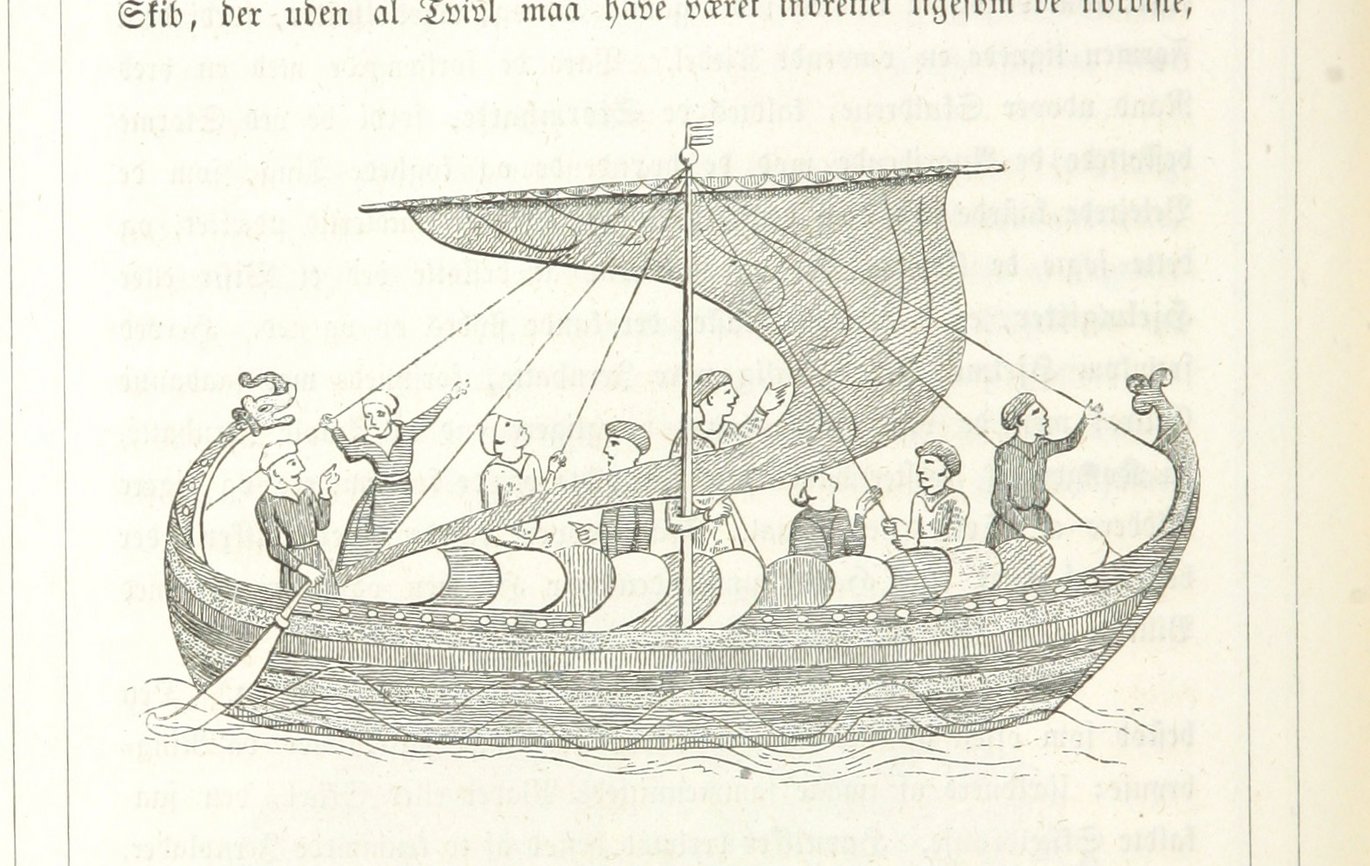

Scandinavian goddesses, gods, and supernatural deities: nowadays it is common to encounter the Norse myths being popularized in the mass media, in electronic games, in cinema and art in general. But in past contexts, they also had a different status, used as elements in the history of nations, in public monuments, in political speeches and in other spheres of society. Adam Fabricius' "Illustreret Danmarkshistorie for folket" (Illustrated History of Denmark for the People) from 1854 was an exhaustive work intended to cover all of Denmark’s history in two volumes. It reflects the concern over the unification of the Kingdom of Denmark and the return of the Duchy of Schleswig to the ‘Fatherland’, which was the main political and national concern of Danish intellectuals and artists at the time; ancestors and myths were used to evoke national romanticism and to underline Denmark’s claim to the Duchy of Schleswig as legitimate. The use of stereotypes, heroes, gods and goddesses as well as mythical events provide a variety of images that readers at the time could identify with – and unashamedly blurred the boundary between ‘myth’ and ‘history’ at a time when evoking nationalism was key.

The book the Illustrated History of Denmark for the People (Illustreret Danmarkshistorie for Folket) was arguably one of the first works to present an illustrated overview of the history of Denmark, from prehistory to the time it was printed, and was very popular until the beginning of 20th century, with numerous reissues being published. The author Adam Kristoffer Fabricius (1822–1902) was a Danish historian, writer and priest. He served as superintendent of Ranum Seminarium, an educational institution for teacher training and was also a teacher of history and French at Aarhus Cathedral school.

Myth taking the place of history

The work of Adam Fabricius is an attempt to reconstruct the Danish past and deals with Antiquity until the Middle Ages in its first volume. The chapter on Nordic history (chapter 2) is essentially composed of Icelandic sagas and this period is referred to as “Paganism”, because the concept of “the Viking Age” was not yet established or popularized by historians. At that time, the sagas were considered direct products from pre-Christian times. However, they were not preserved in writing until a few hundred years later after the arrival of missionaries and the control of the Church.

Today, it is acknowledged that, although the Icelandic sagas are perhaps not as uncontested as “traditional” sources of history which are written contemporaneously, they still provide important information about the time periods, both in which they were written (after 1200) and that to which they refer to (often three centuries before that time). What is key is that they provided a conception of being part of folklore, oral tradition, and ancient customs of peoples. Importantly, it was possible for a reader at the time to enter a historical frame from which there is still little rigorous information from a documentary point of view, but which fulfills the need to know the past.

So, the concept of ‘nation’ presented in Fabricius’ book takes some essential characteristics from myth: he used a much older tradition, that of presenting values, principles, eschatological notions and traditions based on feminine symbols, evoking combatants, the people, the homeland and other elements that could provide a sense of identity.

Romantic ideas of a nation

Fabricius' approach – and that of many of the artists who contributed illustrations to the book – was influenced by the climate of political and territorial tension between Denmark and the German Confederation at that time. The nineteenth century was a period of intense change, where nationalism occupied an important space as an ideological and social framework. The control of the Duchy of Schleswig was the main political element that guided the concern of Danish intellectuals and artists from the 1840s and throughout much of the nineteenth century. The First Schleswig War took place from 1848-1850, instigated by rising tensions between the Danish and the Schleswig-Holsteinian national movements during the 1840s, triggered by the coming to power of a Danish national-liberal government in March 1848. This was immediately followed by a Schleswig-Holsteinian insurrection and war. The Second Schleswig War took place after the publication of the Illustrated History of Denmark for the People in 1864 and saw Denmark losing control of the Duchies to Prussia and Austria. The wars contributed to creating a clear image of Germany as the enemy in Denmark at the time.

The visual arts played a great role in the construction of national identities and themes, essential for countries that sought self-assertion, delimitation of borders and identities within a world that was increasingly globalized, and Fabricius’ book was no different.

The Illustrated History of Denmark for the People

The figure of the ‘hero’

The figure of the hero is frequently used, almost always to do with a situation involving martiality, conflict, danger or glorious death. For example:

- Skiold was one of Denmark's first legendary kings, described by Saxo Gramaticus and Snorri Sturluson, and he is portrayed killing a bear (page 47).

- Uffe was a legendary hero described by Saxo, and was the subject of one of N.F.S. Grundtvig’s poems after the start of the First Schleswig War. He is portrayed killing two enemies (page 52).

- Hrólfr Kraki was a mythical Danish king, of the Skjolding dynasty, with his seat at Lejre in Jutland. He is portrayed attacking Adil (page 59) and his death is also portrayed (page 65).

PICTURE: The woodcut 'Three Valkyries' by Lorenz Frølich from 1850s from the Illustrated History of Denmark for the People, page 41. Photo: Statens Museum for Kunst (The National Gallery of Denmark).

Valkyries and the martial female

The Danish Lorenz Frølich (1820-1908) was the main illustrator of the first volume and his national romantic illustrations played an important role in the book. Frølich's artistic production in the 1850s was politically influenced by the tumultuous period between the two Schleswig wars and reflects the need for armed conflict against the German threat. For example, the opening of the chapter on Icelandic sagas contains the illustration of three Valkyries, Gudr, Rota and Skuld.

The three women, all wearing flat helmets, hold weapons of war. The three Valkyries were mentioned in the Icelandic Prose Edda and listed in Danish translations from the first half of the 19th century. The fact that they were three female warriors was already an iconic tradition in Danish art in the 18th century, as in the musical drama The death of Balder, 1779, by Johann Ernst Hartmann and Johannes Ewald. Somewhat ironically perhaps, the German Confederation also used Valkyries in symbolic ways. In the context of the military humiliations suffered during and after the Napoleonic wars, the Valkyries became national allegories for the countries that made up the German Confederation in the first half of the 19th century. They provided an image of unity, justice, freedom, being positive role models for the conduct of German fighters in battle.

In the Danish context, the Valkyries were members of two great artistic projects, executed by Herman Freund. First in the sculpture Mimir & Balder Consulting the Norns (1822, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek), where Gudur, Rotha and Skuld carry axes and shields, all on foot and also with outfits typical of the ancient Germanics (e.g. with animals on the heads and body). In The Ragnarök Frieze (1827), sponsored by King Frederick VI (1768-1839) for the Christiansborg palace, the sculptor created nine Valkyries that ride with fury, carrying wings and within a neoclassical framework.

In electing these characters to symbolize a mythical past in the Illustrated History of Denmark for the People, the Valkyries become personifications of death, battle, and victory at a time of Northern European romanticism.

PICTURE: Mother Denmark, Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann, 1851, oil on canvas. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen. Photo: Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

The martial model of the Valkyries can be said to have influenced the formation of another important nationalist symbol in Northern Europe: the representation of the country as a female and warlike entity. For example, the painting Mother Denmark by Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann (1819-1881) in 1851 features a young peasant woman holding the Danish flag. She has an energetic attitude and appears to be ready for battle or martial action, haughty and wearing a peasant costume. She also holds a sword and carries a necklace and a diadem, all objects inspired by the Bronze Age and commonly understood to denote that ´history´ is a justification for the defense of the Motherland. The painter was in all likelihood influenced by similar representations in German art, but also by Danish literature, such as the poet N. F. S. Grundtvig, who in 1850 and 1851 wrote poems comparing Denmark with a shield-maiden.

Adapting the sagas: Queen Skuld

In the sub-chapter Roar and Helge, Rolf Krake (chapter 2), an illustration of the moment of King Rolf Krake's death can be found. The scene deals with the final defeat of this legendary king by the army of the Queen Skuld and was essentially based on the Icelandic Saga of King Rolf Kraki. The image shows the king in agony, with an arrow stuck in his chest, with several warriors lying around him and some people complaining about him. The central figure is Skuld, who stands tall and holds a torch aloft, illuminating the face of the fallen king and also to guide her men. She wears chainmail and a helmet with side wings and one of her feet is resting on one of the dead warriors.

PICTURE: Rolf's death by Lorenz Frølich from 1851-1852, the Illustrated History of Denmark for the People, p. 65. Photo: Statens Museum for Kunst (The National Gallery of Denmark).

Somewhat differently, in the Saga of King Rolf Kraki, Skuld is actually described as a witch and a practitioner of magic and together with her army, elves and norns are summoned. During the battle, the Queen positions herself inside a black tent, practicing spells. At no time does the saga mention that Skuld has warrior characteristics, weaponry or conduct similar to a Valkyrie or shield-maiden. This is at odds with how she is portrayed in the Illustrated History of Denmark for the People where for the artist, it seems, a woman who commands an army must necessarily have the characteristics of Odin's female helpers, such as, the use of weaponry.

The Valkyrie as a harbinger of death

The Children of Arngrim, the last image in the saga chapter in Fabricius’ book is that of a naked warrior being taken on a horse and accompanied by a Valkyrie. The horse is black and its rider is presented in dim light, while the woman remains fully illuminated, standing out in the image. With his right hand, the man rests a sword on his thigh (symbol of virility). The Valkyrie rests her arm on the knight's shoulder. Evidently, the illustration has erotic tones. Here, we no longer have the representation of the war maiden, but the one that leads the dead hero to Valhalla, in a subservient and more feminine way. Perhaps Frølich was inspired by The Ragnarök Frieze by Herman Freund, where these characters have wings and also resemble an angel; dying for the homeland appears to have its eschatological and sexual rewards.

PICTURE: Illustration for "Arngrim's Sons", Lorenz Frølich, 1851-1852, drawing, Danish illustrated history for the people, p. 92. Photo: Statens Museum for Kunst (The National Gallery of Denmark).

Myth as History

We have lived at a wonderful time

At least from Fabricus' point of view, the Danes needed a rallying cry against outside forces in the nineteenth century and the use of myth was helpful. It supplemented historical elements, creating a link between paganism and Christianity, and the selection of particular images reflects the intellectual and political context of the time of publication. The Nordic myths and sagas had certainly been used before as an expression of the Danish national spirit, but they arguably took on a special relevance at the time the Illustrated History of Denmark for the People was published in 1954.

| "Vi har levet i en skjøn Tid (d.v.s. Treårskrigen), fuld af opofrende Fædrelandskærlighed. Slesvig blev desværre ej vundet heelt og holdent, skjøndt haarde Kampe er kæmpede. Kampe staae tilbage, men de skulle – det haabe vi – finde os, ligesom Forfædrene, stedse beredte, naar vi ere besjælede af Fædrelandskærlighed og sammen knyttede ved Enigheds stærke Baand." (Quotation from the end of Volume II of the Illustrated History of Denmark for the People). |

| ("We have lived at a wonderful time, full of sacrificial patriotism. Unfortunately, Schleswig was not won completely, although hard battles have been fought. Further battles stand ahead of us, but they will - we hope - find us, like our forefathers, standing prepared, inspired by love of the Motherland and bound together by the strong bond of unity.") (nordics.info translation) |

This is also underlined at the end of the book (Volume II) when Fabricius states that cowards should not figure in historical narratives, but the sacrificial patriotism of heroic figures should be remembered, those who fell in combat particularly. In this sense, the Valkyries and other evocations of myths were allegories that acted as promoters of a glorious nationalistic death. Fabricius also warned of the continuation of the conflict and, in that sense, these symbols were not only able to evoke a strong connection with the nation's past, but served as a political message in creating a rallying cry for the future.

Further reading:

- Adam Fabricius,Illustreret Danmarkshistorie for Folket. [Illustrated Danish History for the People] (Kjøbenhavn: Rittendorff & Aagaard, 1854, vol. I).

- Nora Hansson, 'Klassiskt och nordiskt: Fornnordiska motiv i bildkonsten 1775-1855' [Classical and Nordic: Old Norse motifs in the visual arts 1775-1855], Masteruppsats, Konstvetenskapliga institutionen, Uppsala Universitet (2019), pp. 1-94.

- Inge Adriansen, 'Mor Danmark, Valkyrie, skjoldmø og fædrelandssymbol' [Mother Denmark, Valkyrie, shield maiden and patriotic symbols], Folk Og Kultur, årbog for Dansk Etnologi Og Folkemindevidenskab [People And Culture, yearbook for Danish ethnology and Folk Memory], 16, 1 (1987), pp. 105-163

- Inge Adriansen & Birgit Jenvold, 'Danske myter - fra dronning Thyre til krigen i 1864' [Danish myths - from Queen Thyre to the Second Schleswig War in 1864], Fortid og Nutid 1 [Past and Present], (1998), pp. 5-49.

- Inge Adriansen, 'Danish and German national symbols', Grundtvig-Studier, 44, 1 (1993), p. 66.

- Knut Ljøgodt, 'Northern Gods in Marble: the Romantic Rediscovery of Norse Mythology', Romantik, 1, 1, (2012).

- Margaret Clunies Ross (org.), The Pre-Christian Religions of the North Research and Reception, Vol. I: From the Middle Ages to c. 1830. (Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2018).

- Tim Van Gerven, Is Nordic Mythology Nordic or National, or Both? Competing National Appropriations of Nordic Mythology in Early Nineteenth-Century Scandinavia. In: Simon Halink (ed.), Northern Myths, Modern Identities: The Nationalization of Northern mythologies since 1800. (Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2019, p. 49-72).

Links:

- Glyptoteket

- Unveiling the destiny of a nation: the representations of norns in Danish art (1780-1850) (Article in Perspectives, a digital journal for research articles based on and relevant to research into Danish art, available in English and Danish)

- Uses of history in the Viking ages (In Danish on danmarkshistorien.dk) [Historiebrug af vikingetiden]