Transnational interactions of Nordic disability activism, 1980-2000

In 1981, the United Nations International Year of Disabled Persons (IYDP) shed new light on the global situation of people with disabilities with the slogan ‘full participation and equality’. Based on a longer history of Nordic disability rights activism since the 1960s and the assumption that equal rights of disabled people had by and large already been secured across the Nordic states, the IYDP prepared the ground for an increasing engagement of Nordic experts and activists in global disability issues. In the years to follow, Nordic disability organizations combined their own historical experiences and achievements with regional traditions of internationalism and north-south cooperation to establish themselves as international forerunners in the promotion of disability rights, organization-building and public awareness. Compared with other countries these activities were exceptionally diverse and included regional cooperation, negotiations at the United Nations, transnational exchange, and development projects.

Disability cooperation across the Nordic region

Although disability has historically been viewed primarily as a national matter connected to domestic charity and welfare, medical advances and the emergence of new public health practices around 1900 also led to frequent international exchanges. Already in the late 19th century Nordic policymakers, social reformists and public health professionals came together at what was termed “meetings on abnormal matters” (abnormsaksmöten) to discuss the situation of blind, deaf-mute, and physically and intellectually disabled people across the region. In the years that followed, these meetings provided the basis for more differentiated networks of professionals, like the Nordic Orthopaedic Federation (Nordisk Ortopedisk Förening, 1919), the Nordic Society for Special Education (Nordiska Förbundet för Specialpedagogik, 1922) and the Nordic Society for the Welfare of Cripples (Nordisk Vanförevårdsförening, 1934 (no longer in existence)).

With the building of modern welfare states and the integration of the Nordic region after 1945, a more concerted political effort for the advancement of disability issues began. In 1953 a Nordic convention on invalidity pensions was passed, followed in 1957 by a convention on social security (Nordisk konvention om social trygghet). The Nordic Council and the Nordic Council of Ministers have over the years dealt with disability issues through publications, seminars and guidelines for the Nordic governments that focused on the coordination of welfare benefits, rehabilitation measures, special education and vocational training as well as on technical devices and public transportation for disabled people. To better coordinate these efforts, the Nordic Council established the Nordic Committee on Disability (Nordiska nämnden för handikappfrågor, NNH) in 1976. Today, disability forms a sub-area of the Nordic Welfare Centre, an institution of the Nordic Council of Ministers.

| Nordic convention on reciprocal allowance/payment of benefits on grounds of reduced working ability (Nordisk konvention om ömsesidigt utgivande av förmåner i anledning av nedsatt arbetsförmåga) |

| According to this convention, persons with reduced working ability due to illness or disability who had moved to another country or had acquired the disability there, had the right to access the same social insurance and benefits as citizens of that country. It later became part of the convention on social security, which followed the same principle but included access to a broader range of welfare services like old age pensions, though in some cases the country of origin remained responsible for the payments. The social security convention was signed by the social ministers of the Nordic countries in 1955 and ratified by all five national governments in 1957. It was updated in 1981 and 2004. |

After years of lively but rather informal exchanges between national disability organizations representing different types of disabilities (blindness, hearing loss, mobility impairments etc.), the second half of the 20th century also saw the establishment of regional associations, such as:

- the Nordic Cooperative Committee of Blind Organizations (Nordiska Blindorganisationernas Samarbetskommitté, 1943),

- the Nordic Disability Federation (Nordiska Handikappförbundet, 1946),

- the Nordic League for Mental Handicap (Nordiska Förbundet Psykisk Utvecklingshämning, 1967), and

- the Nordic Council of the Disability Organizations (Handikapporganisationernas Nordiska Råd, 1979

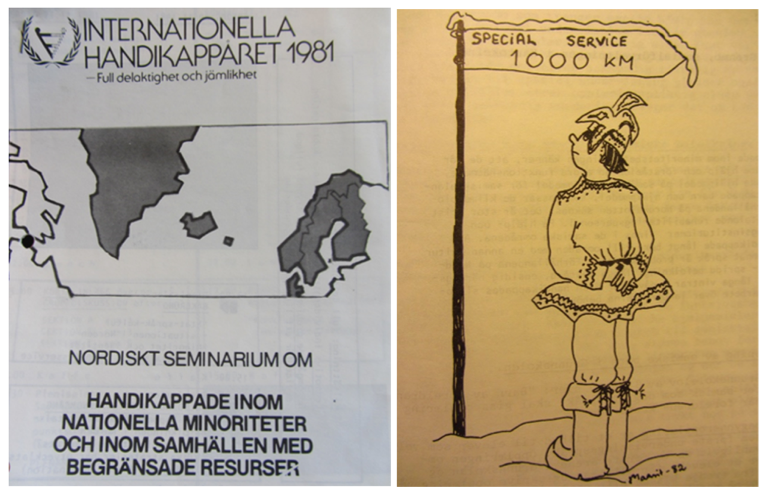

Approaching disability from a societal and environmental perspective, the development of joint political strategies as well as public awareness campaigns became a priority for these associations. An example of this non-governmental cooperation is the Nordic seminar on ‘Disabled Persons among National Minorities and Societies with Limited Resources’ in 1981: Organized by disability activists and organizational representatives, it discussed disabilities among the Norwegian Sámi, Greenlanders, Åland islanders and Swedish-speaking Finns – minority groups that at the time received only marginal attention by policymakers and public authorities.

| Disabled People’s International (DPI), founded in 1981 as the first transnational organization run by persons with disabilities, held a world council meeting and symposium in Stockholm in 1987 that was organized by Bengt Lindqvist. From left to right: Barbro Carlsson (DPI, Sweden), Norman Acton (International Council on Disability, US), Henry Enns (DPI, Canada), Bengt Lindqvist (DPI, Sweden) and Joshua Malinga (DPI, Zimbabwe). Photo: DPI-Calling – European Regional Newsletter, 3, 1987, p. 9. Reused with kind permission of DPI. |

Inter- and transnational disability activism

Normalization and intellectual disabilities

Regional cooperation also resulted in a strong involvement in inter- and transnational discourses of disability. The years after 1945 saw a growing number of professional networks and congresses that put special emphasis on the situation of persons with intellectual disabilities, discussing among other things accommodation and care in institutions as well as medical approaches and eugenic practices. Eugenic laws like national sterilization acts, marriage bans and abortions had devastating consequences for disabled persons until their eventual demise and abolishment in the 1960s and 1970s. The Nordic countries in terms of population numbers reached levels of institutionalization, sterilizations and lobotomies that were among the highest in the world. It is therefore somewhat of a paradox that, within these debates, Nordic experts emerged as representatives of a modern approach to care called ‘normalization’, which meant that people with intellectual disabilities had a right to the same daily routines and living conditions as their non-disabled peers.

PICTURE: Cover and illustration (p. 67) from the Nordic seminar report “Disabled persons among national minorities and societies with limited resources”, Samarbetsrådet för handikappsfrågor i Svensk-Finland, Ålands Landsskapsstyrelse, Helsinki 1981 (1982). Photos: Anna Derksen.

The concept of normalization was first introduced in 1959 by Niels Erik Bank-Mikkelsen from what was then called the Danish Service for the Mentally Retarded (Statens Åndssvageforsorg) and further developed by Bengt Nirje from the Swedish Parent Federation for Mentally Handicapped Children (Riksförbundet för Utvecklingsstörda Barn, FUB). Both Bank-Mikkelsen and Nirje promoted normalization internationally, thereby turning it into a key principle for advancing the rights of persons with intellectual disabilities worldwide. This arguably led to the International League of Societies for the Mentally Handicapped becoming committed to normalization in 1968 and principles espoused in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Mentally Retarded Persons in 1971.

Although institutions remained the dominant form of care for intellectually disabled persons in the Nordic countries until the 1970s and 1980s, subsequent deinstitutionalization and the use of small-scale residential care became an influential international model. Personal budgets for purchasing social care and assistance services based on individual needs, initiated in Sweden in 1994 with the Act concerning Support and Service for Persons with Certain Functional Impairments (Lag om stöd för visa funktionshindrade, LSS), were subsequently adopted by the neighboring Nordic states and a growing number of other countries.

Building a transnational disability community

The International Year of Disabled Persons (IYDP) in 1981 brought additional momentum to transnational exchange. Organized by the United Nations, its main purpose was to discuss ways to improve the situation of people with disabilities in developing countries. In preparation for the IYDP, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched a new classification of disability and promoted community-based rehabilitation (CBR) as an innovative method in development interventions that included not only disabled individuals, but also their families and local networks. The concept was formulated by Einar Helander, a Swedish physician working for the WHO, and the Nordic countries readily supported CBR as a tool to mobilize local support for disabled persons in developing countries.

A key turning point for the representation of persons with disabilities in international nongovernmental organizations, many of which were still dominated by able-bodied professionals, was the congress of Rehabilitation International in Winnipeg in 1980. In order to challenge what they saw as an outdated perpetuation of a medicalized view on disability, a group of participants with disabilities, among them Bengt Lindqvist from Sweden and Holger Kallehauge from Denmark, decided to leave the congress and instead formed Disabled Peoples’ International (DPI), the first transnational disability organization run by persons with disabilities themselves. As elected secretary, Lindqvist became entrusted with drafting the organization’s statutes and establishing a regional office in Sweden.

United Nations and international organizations

People with disabilities were even taking part in the more diplomatic circles of the United Nations and other international organizations, advocating for international legal frameworks for the protection and equal rights of persons with disabilities, as well as addressing other issues. In preparation for the IYDP it was particularly the Swede Bengt Lindqvist and Holger Kallehauge from Denmark, both disabled and active in various disability organizations in their respective home countries, who conveyed views and ideas on disability rights to the United Nations. They participated, for example, in meetings of the UN planning committee for the IYDP and insisted on greater involvement of disability activists in the final documents for the IYDP and international policy-making - with some success. In 1993, Lindqvist was tasked with drafting the UN Standard Rules for the Equalization of Opportunities of Disabled Persons and became first UN Special Rapporteur on Disability from 1994 to 2002.

PICTURE: Karl Henrik Seemann (centre) from Norway, one of a group of disabled athletes visiting the UN Headquarters in New York during the International Year of Disabled Persons in 1981. UN Photo/John Isaac.

Common to these initiatives was to further disability as a global human rights issue while bringing in social-relational dimensions of disability. In addition to personal and organizational links between Nordic disability organizations and later global activities, it is possible to trace a similar use of terminology, like the concept of a ‘society for all’ that was for instance used by Swedish disability organizations in the 1970s that was later used, for example, in a number of UN conferences and a long-term strategy from 1998 entitled ’Towards a society for all in the twenty-first century’. Together with participants from other countries, Nordic disability rights activists were also influential in the drafting of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) from 2006. It is widely accepted that milestones such as these have added further momentum to transforming the social, political and economic situation for persons with disabilities – in domestic politics, but also as reference point for a continued inter- and transnational engagement.

Further Reading

- B. E. Eriksson and R. Törnqvist, Rolf (eds.) Likhet och särart. Handikapphistoria i Norden [Equality and Difference. Disability history in the Nordic countries] (Nynäshamn: Handikapphistoriska föreningen, 1995).

- Borgunn Ytterhus, Snæfríður Þóra Egilson, Berit Berg and Rannveig Traustadóttir, eds., Childhood and Disability in the Nordic Countries. Being, Becoming, Belonging (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

- Diane Driedger, The Last Civil Rights Movement: Disabled Peoples' International (London and New York: Hurst and Co. / St. Martin's Press, 1989).

- G. M. Cederstam (ed.) Vägen till människovärde. Några drag ur nordisk handikapphistoria åren 1945-1985 [The road to human dignity. Some features from Nordic disability history in 1945-1985] (Vällingby: Nordiska nämnden för handikappfrågor, 1990).

- Oddný Mjöll Arnardóttir and Gerard Quinn, eds., The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. European and Scandinavian Perspectives, (Leiden: Brill / Nijhoff, 2009).

- S. T. Egilson, B. Berg and R. Traustadottir (eds.) Childhood and Disability in the Nordic Countries. Being, Becoming, Belonging (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).