Feminist writing in the Nordics, 1970s-2000

Feminist writing in 1970s, particularly prose fiction, was inspired by second-wave feminism and by the mid-1980s, feminist writing had become a significant element in Nordic culture. Over the following two decades, issues of gender, frequently explored in terms of language, identity and the body, also gave new prominence to genres such as drama and poetry.

Second-wave feminism

In the Nordic countries, the aftermath of the Second World War was not a context conducive to feminist writing, that is, writing that challenges the prevailing inequalities (economic, political, social) between women and men, creates spaces for alternative relationships, and explores the implications of these. But, from the early 1970s onwards, second-wave feminism inspired a wide range of feminist work, especially prose fiction investigating the conditions of women.

With regard to political institutions, women in the Nordic countries had cleared the thresholds of legitimation (the right to meet and speak in public), incorporation (the right to participate in elections) and representation well before the war, but their participation in the exercise of power did not begin in earnest until the 1970s and 1980s. For a couple of decades after the war, women’s economic activity remained relatively limited, with no marked increase occurring until the 1970s and 1980s.

However, in the early 1960s, gender roles became a major topic of public debate in both Sweden and Finland, thus anticipating second-wave feminism (the first wave had focused on women’s suffrage) which reached the Nordic countries from Britain, France and the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Creating a climate of political activism and foregrounding issues such as political and economic inequality, abortion and pornography, second-wave feminism also inspired a multi-faceted feminist culture that included art, music, theatre and film. Nordic feminist writing of the 1970s and 1980s is part of this highly visible and dynamic culture.

Subverting the male cannon

Elisabet Hermodsson’s (Sweden) book Disa Nilssons visor (1974) (The Songs of Disa Nilsson) subverts the gender roles in a work by a male poet, Birger Sjöberg, published half a century previously and were set to music by the author. Together with Wava Stürmer’s (Finland) texts for Sångbok för kvinnor (1973) (Songbook for Women), they became central to the new women’s movement in several of the Nordic countries. Bjørg Vik’s (Norway) To akter for fem kvinner (1974) (Two Acts for Five Women) is an example of feminist drama: a realist play, its women characters are looking afresh at their roles. By contrast, Suzanne Osten’s and Margareta Garpe’s (both from Sweden) play Jösses flickor (1975) (Good God Girls) draws on Brechtian techniques to trace the history of the Swedish women’s movement from a radical perspective.

Diversity of genres

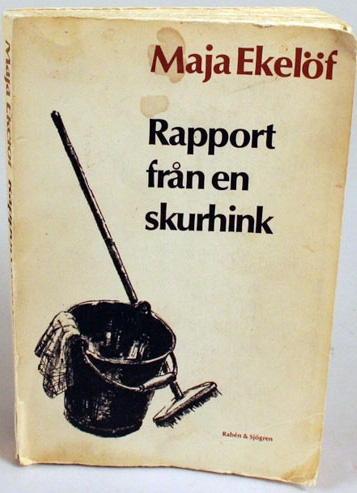

Whilst the prose genres dominated Nordic feminist writing in the 1970s and 1980s, the sheer range of genres is probably the most conspicuous feature. The report book was directly related to the consciousness-raising of second-wave feminism. Collective volumes such as Kvinder på fabrikk, I-II (1971, 1977) (Women in Factories) and Kvinder i hjemmet (1972) (Women at Home), both produced in Denmark, are typical examples. The genre was explored by individual authors too, with Maja Ekelöf’s (Sweden) Rapport från en skurhink (Report from a Slop Bucket) causing a sensation in 1970.

PICTURE:"Report from a Slop Bucket" (Rapport från en skurhink) by Maja Ekelöf published in Sweden caused a sensation in 1970. Photo: Jamtil, Europeana CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

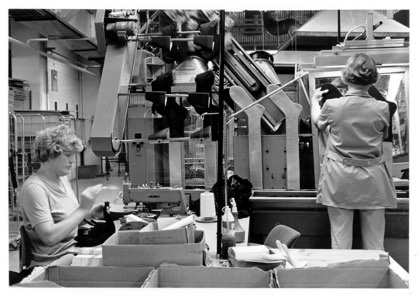

Prose fiction throughout the 1970s and 1980s investigated the conditions of women from a range of perspectives. Liv Køltzow’s (Norway) novel Hvem bestemmer over Bjørg og Unni (1972) (Who Decides about Bjørg and Unni?) is an example of feminist realism, as are Dea Trier Mørch’s (Denmark) Vinterbørn (1976) (Winter’s Child, 1986), about a group of women and their experiences of pregnancy and childbirth, and Oddvør Johansen’s (Faroe Islands) Lívsins summar (1982) (The Summer of Life), an exploration of motherhood and art. Novels such as Märta Tikkanen’s (Finland) Män kan inte våldtas (1975) (Manrape, 1978) and Gerd Brantenberg’s (Norway) Egalias døtre (1977) (The Daughters of Egalia, 1985) expose gendered inequality by means of inversion. Explorations of language and genre helped to shed light on the construction of gendered identity and on femininity in particular. In Kerstin Ekman’s (Sweden) tetralogy about industrialisation and urbanisation, epitomised by the transformation of a railway station into a town (1974-83), the realist exploration of the conditions of women in the first three volumes gives way in En stad av ljus (1983) (City of Light, 2003) to a first-person narrative that problematises gendered identity in the context of cultural and perceptual border areas.

Covering a range of genres, the work of Eeva Kilpi (Finland) focuses on the construction of the male body as well as feminine autobiography, while Kirsten Thorup (Denmark) pinpoints gendered subordination by means of language in a novel such as Baby (1973) (Baby, 1980), and opens up critical perspectives on modern Danish society in the tetralogy about Jonna (1977-87).

Eeva-Liisa Manner (Finland) has drawn on philosophy to formulate a social critique that also includes modern technology, while the novels of Bergljot Hobæk Haff (Norway) illustrate a shift from realism to a growing preoccupation with the traditions of oral narrative and myth.

PICTURE: Prose fiction throughout the 1970s and 1980s investigated the conditions of women from a range of perspectives, both at work and at home. Women are working here in a Finnish sock factory during the 1970s. Photo: Nurmes Town Museum, finna.fi. CC BY 4.0

Suzanne Brøgger (Denmark) has pointedly mixed genres as she has investigated marriage, the nuclear family and monogamy from radically different angles, frequently including an autobiographical dimension. In the novels of Dorrit Willumsen (Denmark), the reification of woman opens up for the grotesque as exemplified by Programmeret til kærlighed (1981) (Programmed for Love), a novel about a living doll constructed by a female engineer who takes men’s craving for the ideal woman literally. In the work of Svava Jákobsdóttir (Iceland), women’s traditional roles are deconstructed by means of a concretisation of words and concepts that results in effects that are both fantastic and grotesque, e.g. in the short stories in Veizla undir grjótvegg (1967) (Party beneath a Stone Wall).

Experimenting with form from the 1980s

By the mid-1980s, feminist writing had become a powerful element in Nordic culture, boldly exploring more wide-ranging issues of gender by means of a range of innovative techniques. Inspired by theoretical advances, the postmodern problematisation of language, identity and the body has become central, while at the same time the feminist writing of the 1960s and 1970s has gradually been succeeded by writing preoccupied with more fundamental and wide-ranging issues of gender. These developments have helped reinforce the prominence of texts as new discursive spaces.

Cecilie Løveid (Norway) had her breakthrough as a playwright in 1982 with the radio drama Måkespisere (Seagull Eaters, 1989). Her stage plays include Balansedame (1984) (Tightrope Lady) and Dobbel nytelse (1990) (Double Delight), both exploring sexuality, communication and power in mother – daughter – father relationships, and using innovative visual effects to enhance – or subvert – the spectator’s involvement. Kristina Lugn (Sweden) had achieved a reputation as a poet writing about alienation in everyday language by the time she emerged as a playwright in the 1980s. Love and power relationships are recurring themes in her dramas for radio, television, and the stage.

The poet Inger Christensen (Denmark) was a leading modernist/post-modernist writer. While the poems in det (1969) (it) investigate the relationships between the self, cosmos and language against a sophisticated theoretical background, the sonnets in Sommerfugledalen (1991) (Butterfly Valley) serve as a precise framework for an exploration of poetry and life.

The poet Inger Christensen (Denmark) was a leading modernist/post-modernist writer. While the poems in det (1969) (it) investigate the relationships between the self, cosmos and language against a sophisticated theoretical background, the sonnets in Sommerfugledalen (1991) (Butterfly Valley) serve as a precise framework for an exploration of poetry and life.

PICTURE: Inger Christensen (1935-2009) was a Danish poet, novelist, essayist and editor. She is considered the foremost Danish poetic experimentalist of her generation. Here, she is reading from one of her works in 2018. Photo: Johannes Jansson, norden.org

Pia Tafdrup (Denmark) frequently reads her poems in public, her performances reinforcing the texts’ preoccupation with the body. In her work, nature and cosmos emerge as Other in an œuvre characterised, in collections such as Hvid feber (1986) (White Fever) and Krystalskoven (1994) (Crystal Forest), by a consistent foregrounding of the aesthetic. The poetry of Eva Ström (Sweden) with its sharply focused images and metaphors frequently has the female body at its centre, with the search for feminine identity in Steinkind (1979) (Steinkind) involving role play; in Revbensstäderna (2002) (Rib Cities) the conflation of the anatomy of the city with the human body fuses not just humanity but life across the species boundaries. The work of Katarina Frostenson (Sweden) is preoccupied with the creation rather than the narration of experience, the fragmented texts that establish the shiny surface of a welfare society also opening up for that which can tear the established order apart. Here language is matter, with the poems in Joner (1991) (Ions) constructing gender hierarchies in terms of linguistic power.

The French theorist Luce Irigaray’s understanding of language as a masculine construct, allowing no space for the feminine, has provided an impetus for the work of Karin Moe (Norway). Her novels Blove 1.bok (1990) (Blove. Book I) and Blove 2.bok (1993) (Blove. Book II) link the fluidity of language with the eroticism of the female body to satirise patriarchy. The prose fiction of Inger Edelfeldt (Sweden) develops a kaleidoscope of registers to investigate gender relations and the destructive impact of feminine socialisation, e.g. in the short stories in Den förunderliga kameleonten (1995) (The Remarkable Chameleon) and the novel Finns det liv på Mars? (2006) (Is there Life on Mars?). Preoccupied with themes such as art, sexuality and death, the œuvre of Vigdís Grímsdóttir (IS) has drawn both on magic realism, as in the novel Kaldaljós (1987) (Cold Light), and on forms that transgress genres and registers, as in the novel Z Ástarsaga (1996) (Z -- A Love Story, 1997). The novels of Monika Fagerholm (Finland) highlight their significance as artefacts, with Den amerikanska flickan (2004) (The American Girl) and Glitterscenen (2009) (The Glitter Scene) exploring the subjectivity of young girls and generations of women respectively in highly original prose. Fagerholm’s Lola uppoch ner (2012) (Lola Upside-Down) uses the genre of crime fiction for investigations into language and literary genre in a small-town setting.

This article has been published posthumously.

Further reading:

- Helena Forsås-Scott, ‘Egalitarianism and Feminist Consciousness: Feminist Writing in Scandinavia’ (1991), in H. Forsås-Scott, ed., Textual Liberation: European Feminist Writing in the Twentieth Century (London: Routledge; 2nd ed., 2014).

- Helena Forsås-Scott, Swedish Women’s Writing 1850-1995 (London: Athlone Press, 1997).

- Janet Garton, Norwegian Women’s Writing 1850-1990 (London: Athlone Press, 1993).

- Elisabeth Møller Jensen (ed.) Nordisk kvindelitteraturhistorie, vols. 4-5, available online at www.nordicwomensliterature.net (1997, 2000).