1970s feminist culture in the Nordics

The feminist movement that flourished in the Nordic countries during the 1970s had strong roots in anti-capitalist, socialist ideology. It was powered by a host of social events, community building, artistic creation and political activism.

A lively feminist culture developed in the Nordic countries in the 1970s. Inspired by second-wave feminism, women in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Iceland and, to a lesser extent, Finland organised into groups and formed organisations. Women became more visible as they promoted and created a culture of their own, and a feminist public sphere evolved. Among radical feminists, art was regarded as a significant part of the political struggle.

Many feminists shared a belief in socialism and anti-hierarchical organisational forms. For example, the Danish Rødstrømpebevægelsen, named after the American Redstockings, developed a culture involving meetings in small groups, the forming of networks, and the occasional participation in communal activities. Consciousness raising by means of the sharing of experiences was regarded as fundamental.

Under the slogan ‘the personal is political’ phenomena perceived as taboo, personal or insignificant in mainstream culture were made part of the project of liberation. In Dane Suzanne Giese’s Redstocking novel På andre tanker (1978) (Thinking Differently), women who have just been to a meeting discuss masturbation and orgasm as naturally as they do education and work. In Søstrene (1979) (The Sisters), Ulla Dahlerup (also from Denmark) thematised sisterhood and the importance of sharing experiences in women’s groups. The Redstockings’ summer camps for women on the Danish island of Femø attracted participants from all the Nordic countries, eager to take part in and develop feminist culture.

In most Danish cities throughout the 1970s, kvindehuse (women's houses) were set up. This poster advertises the move to Prinsessegade 7 of one such house. In the bottom lefthand corner, it states, "birth preparation, workshop, book cafe, film evenings, clothes-swapping, house meetings, lesbian meetings, Lesbian Movement and Redstocking Office. Photo: Europeana , Kulturstyrelsen , CC BY.

The issue of lesbianism caused conflicts in the feminist movement. At the time the subject was taboo in the public sphere. An epoch-making event occurred when Gerd Brantenberg, the first openly lesbian Norwegian writer, published a book on homosexuality under her full name (1973).

The socialist Grupp 8 (Group 8), founded in 1968, became central to second-wave feminism in Sweden. In 1970 Nyfeministene (New Feminists) was founded in Norway, followed by the Kvinnefronten (Women’s Front) in 1972, Claragruppen (The Clara Group) in 1974, the Lesbisk Bevegelse (Lesbian Movement) in 1975, and Brød og Roser (Bread and Roses) in 1976. A vital part of socialist second-wave feminist culture is the protest against repressive power structures and institutions of the capitalist welfare state. In Iceland, where the Redstockings became strong and influential, a nation-wide women’s strike took place on 24 October 1975, a separate list of women candidates was introduced at the election to the Althing in 1983, and in the same year a feminist political party was established. In Finland, on the other hand, an extensive debate on gender roles had been going on throughout the 1960s, and one of the effects was to reduce the impact of second-wave feminism. But the radical group Yhdistys 9 (Association 9), founded in 1966 to work for gender equality, used some of the same artistic media favoured by Nordic feminist organisations, notably theatre.

One important art form was the feminist song, often written and sung at meetings, camps and festivals. The record Kvinder i Danmark (Women in Denmark) by members of the Redstockings was released as a collective work in 1975. Many of the songs combine new texts with the tunes of well-known pop songs, a concept also used by the Swedish group Röda bönor (Red Beans/Red Chicks). With radio programmes such as Spinnrock (Spinning Wheel) feminist music was integrated into national mass media. In Norway the groups Amtmandens døttre (The District Governor’s Daughters, named after Camilla Collett’s pioneering novel), and Kjerringrokk (Hag Rock) released records of feminist songs and folk music.

Feminist drama also flourished. Norwegian Bjørg Vik’s To akter for fem kvinner (1974) (Two Acts for Five Women) exposes the artificiality of women’s roles. Anti-hierarchical groups produced political and didactic plays, often integrating non-fiction such as reportage and songs. Liv Køltzow and Anja Breien from Norway were part of the group behind Jenteloven (1972) (The Law of Girls), in which women who have been staying at home go out to work. Suzanne Osten’s and Margareta Garpe’s Jösses flickor! Befrielsen är nära (1974) (Good God Girls! Liberation is Near), a milestone in feminist theatre in Sweden, is another example of feminist political theatre.

Film and television were also central to the airing of feminist issues. Anja Breien’s film Hustruer (1975) (Wives) contrasts the liberation of sisterhood with the frustrations of the role of the wife. Carin Mannheimer (1934-2014, SE) voiced social criticism in television series such as Dela lika (1972) (Share Equally) and Lära för livet (1977) (Learning for Life), broadcast at prime time.

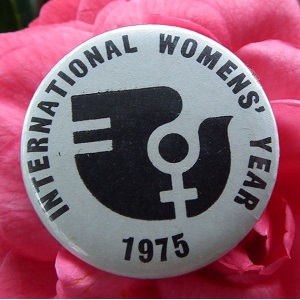

In 1975, the United Nations’ International Women’s Year, there were art exhibitions promoting women’s art in Copenhagen, Stockholm, Oslo, Reykjavík and Helsinki. Part of the feminist project was to highlight a forgotten heritage consisting of works by women artists from earlier periods. The projects of reclaiming a women’s tradition and constructing an historical identity for women were expressed in various art forms, and also in the establishment of women’s museums and the academic discipline of women’s studies.

Since the mid-1980s, feminism as political activism has become less prominent. Analyses of constructions of gender and a better understanding of cultural dynamics and complexities have resulted in a multiplicity of feminist cultures, ranging from subcultures publishing zines (e.g. the Swedish anarco-feminist Radarka) to those integrated into public institutions. In all the Nordic countries there are meeting places for a diversity of women’s cultures (e.g. the women’s museum in Kongsvinger, Norway), centres for women’s and gender studies, and also a Nordic Institute for Women’s Studies and Gender Research.

An electronic women’s sphere has evolved with websites (e.g. the Swedish queer site Caos), e-journals (e.g. the Swedish Darling), blogs etc. The dynamics of postmodernism, multiculturalism and technology have changed both feminism and culture, certainly since the 1990s.

References

- D. Dahlerup, Rødstrømperne: den danske Rødstrømpebevægelses udvikling, nytænkning og gennemslag, 2. vols. (Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1998).

- E. Witt-Brattström, Å alla kära systrar: historien om mitt sjuttiotal (Stockholm: Norstedt, 2014).