An Overview of Faroese literature

Faroese literature has almost two hundred years behind it, and despite a limited number of inhabitants, authors and publications, a multitude of literary trends and techniques are represented.

Summary: National sentiment has been strong in Faroese literature since it first became a written language in the nineteenth century. The assertion of Faroese against the dominant Danish language and culture remains important, although some of the most famous Faroese authors have in fact written in Danish, such as, William Heinesen and Jørgen-Frantz Jacobsen. Faroese literature has also been influenced by the development of different literary periods, just like elsewhere.

Faroese fiction began in the late 18th century with the collection, recording, and publication of Faroese oral poetry, which had its roots far back in history. Faroese spelling was first constructed in 1846, an important milestone providing the tools that enabled the writing of contemporary poetry and prose, activities which subsequently began to take off in 1876 when Faroese students at the University of Copenhagen wrote the first poems about the Faroe Islands.

In other words, the first Faroese poetry to be written down was patriotic and played a part in asserting the Faroese language and culture against the dominant and official Danish language. Nationalist currents still flow through Faroese literature, even if they are gradually diminishing. That said, alternative currents, including those flowing through different literary waves in general, also continue to influence the literature coming out of the Faroe Islands.

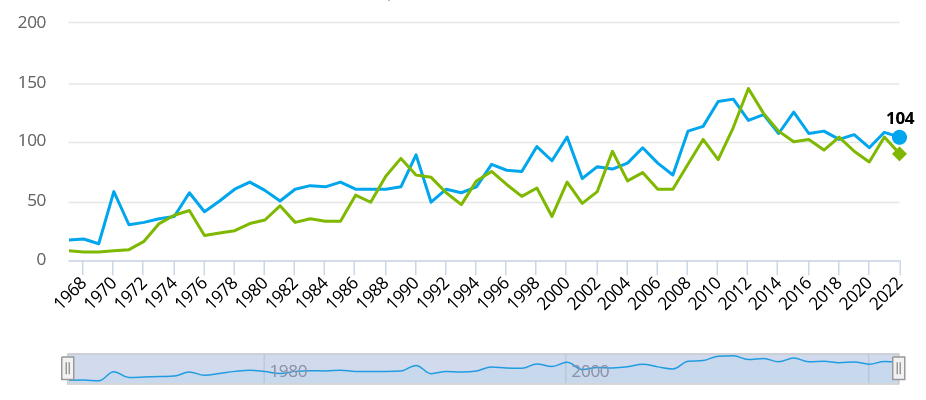

The number of literary works in Faroese over time

In 1822, the first book in Faroese was published, the folk song about Sigurd Fafnersbane. In 2022, 194 books were published: 104 were original (of which 21 were fiction), and 90 were translations (of which nine were fiction).

Symbolism and naturalism at the beginning of the 20th century

Faroese literature in the first third of the 20th century was characterised by symbolism and naturalism. The first novel in Faroese, Bábelstornið (The Tower of Babel) by Rasmus Rasmussen, published in 1909, is naturalistic and depicts the rise and development of the nationalist movement through three generations in two competing families of farmers. J.H.O. Djurhuus's poetry collection Yrkingar (Poems) from 1914 also makes use of a symbolist style which, combined with vitalism, characterises the poets who debuted in the 1920s, most notably William Heinesen (1900-1991) and Christian Matras (1900-1988).

William Heinesen and Jørgen-Frantz Jacobsen (1900-1938), who both wrote in Danish, are by far the best-known Faroese authors. Their novels (seven by Heinesen and one by Jacobsen) have been translated into many languages, including Faroese, and even made into films.

The 1930s saw the publication of novels which continued the description of the old farming community, but now with a greater emphasis on the departure from peasant life in favour of fishing and fishing families. This includes novels such as William Heinesen's first novels Blæsende Gry and Noatun (Windy dawn, 1934 and 1938, respectively) as well as Heðin Brús' Lognbrá and Fastatøkur (Mirage, and Firm grip on life, 1930 and 1935) and Feðgar á ferð (1940; The Old Man and his Sons). The transition is completed in Martin Joensen's two critically realistic novels Fiskimenn and Tað lýsir á landi (Fishermen, and It's getting brighter on land, 1946 and 1952) about fishermen and fishing, the working class and capitalism, and about life in a market town, faith and love.

The post-war period

In 1938, Faroese became a fully fledged subject in school. Danish had up until then been both the main academic as well as spoken language, and then, in 1948, the Home Rule Act made Faroese an official language equal to Danish. This meant that the writers who debuted in the 1950s had learned to read and write Faroese from their first days at school, and they no longer had to develop Faroese literary language as a “basic tool” alongside the creation of their literary works. Now modernism became the dominant form of poetry as well as prose.

Jens Pauli Heinesen (1932-2011) began a long career in prose writing in 1953 with 26 works consisting of short stories, novels, drama and essays, where issues in the arts are a recurring theme, as in the debut novel Yrkjarin úr Selvík og vinir hansara (The poet from Selvík and his friends, 1958). In the socially critical novel Frænir eitur ormurin (The worm is called Fafner, 1973) the clash between democratic, socialist and outright reactionary forces are depicted, culminating in fascist conditions where freedom of assembly and of writing are banned. A memoir in seven volumes depicts the author's path to authorship, Á ferð inn í eina óendaliga søgu (Travelling into an infinite story, 1980-1992), where the title alludes to Marcel Proust's À la recherche du temps perdu. The boy's development is set in an environment shaped by the great world events of the time; Nazism and the Second World War, and the struggle for power between the Soviet Union and the United States. The consequences of this can be found in the little boy's upbringing and youth.

The post-war period was characterised by the Cold War and accelerating societal development, which also left its mark on poetry. Rói Patursson (b. 1947) is the Faroese poet of the youth rebellion. He made his debut in 1969 and received the Nordic Council Literature Prize for his third poetry collection, published in 1985, Líkasum (Likewise) in 1986. The long poem Sólareygað (The eye of the sun) in particular is interesting for its form and visionary content.

Jóanes Nielsen (b. 1953) debuted in 1978 as a socialist rebel poet who especially used powerful metaphors built around diesel engines and fierce eroticism. Nielsen's first novel was published in 1991 with the narrative title Gummistivlarnir eru tær einastu tempulsúlur sum vit egia í Føroyum (The wellington boots are the only pillars of worship we own in the Faroe Islands). Several of his poems and novels have been translated into Danish, including the novel Glansbílætasamlararnir (2005; Picture collectors - Billedsamlere, in Danish). In the period 2011-2022, Nielsen published a powerful family history that begins in 1846 and ends around 2020, of which the first volume Brahmadellarnir was published in English, The Brahmadells, in 2017. Nielsen has published nine poetry collections, seven novels, three plays as well as numerous articles and essays.

Tóroddur Poulsen (b.1957) debuted as an angry young man in Faroese poetry in 1984 and has since published a multitude of poetry collections, often several a year – a total of 47 works. His form is modernist, the attitude postmodernist, and it is very inventive linguistically. He is distinctly experimental in his prose, music and especially within the visual arts.

Women gradually asserted themselves more in the post-war period. The first book by a woman was a drama from 1903, and the next a story in four volumes published in 1950-1973 by Johanna Maria Skylv Hansen (1877-1974). In 1963, the first complete collection of modernist poems in Faroese was published, Guðrið Helmsdal Poulsen’s Lýtt lot (Warm breeze), with nature-inspired poems about the poet's search for coherence in life and the poems' own creation. The first novel written by a woman was published in 1971, Rannvá by Dagmar Joensen-Næs (1895-1983). It depicts how a young woman is seduced by the country's most distinguished official. In the following decade, feminism broke through in fiction with the novel Lívsin summar (Life’s summer) from 1982, about the girl Nora and her family who strives to expand their house so they have space for the father’s carpentry workshop. Nora’s mother and the friend's mother represent two different feminist paths to self-realization. Bergtóra Hanusardóttir (b. 1946) debuted in 1984 and in 2006 published the novel Burtur (The Faroese) about Faroese students in Copenhagen in the 1960s, which focuses on women's feelings of alienation and exposure to masculine dominance and violence.

Faroese fiction is also characterised by postcolonialism, that is, the fiction is marked in different ways by the relationship to the Danish language and to Denmark.

The 21st century

As a rule, Faroese writers cannot make a living from their art, but need to combine it with ordinary paid work and write in their spare time and holidays. However, Jens Pauli Heinesen and Carl Jóhan Jensen (b. 1957) have been full-time writers, and Jensen, partly like William Heinesen before him, has made a name for himself with a strict modernist form in poetry as well as in prose. Jensen's stated goal with his poetry is to create a new language so that readers have the opportunity to expand their awareness of themselves and the world. He does this by writing in a Faroese which is characterized by rarely used words and expressions, making it more difficult to grasp his work compared to many other authors. This applies to his novels as well, all of which are large and comprehensive both in terms of action, ideas and language. He is also one of the Faroese authors who have received the most awards, including for his novel Ó-, søgur um djevulskap (Tales of devilry) from 2005.

The resurgence of the secession movement around the turn of the millennium is the subject of Silvia Henriksdóttir's novel written in Norwegian, Djevelen kan ikke lese (The devil can't read, 2014), where an imagined secession is part of the crime novel plot. The law-and-literature novel Vit, Føroya fólk (We, the Faroese people) from 2019 by Bjørk Maria Kunoy (b. 1991) depicts how work on a Faroese constitution is finalised. The realism of the novel is counterfactual as the constitution, which politicians were actually working on at the time, was never finalised, partly due to disagreements over whether it should lead to secession or simply be a constitution within the existing framework.

Ecocriticism has received a lot of literary attention, from the young adult novel Sum rótskot (Like a sprout) from 2020, by Marjun Syderbø Kjelnæs (b. 1974) about high school students' action on behalf of the climate, to dark ecocritical poems in publications like Kim Simonsen’s (b. 1970) Desembermorgun from 2015 (December morning).

The Faroese parliament has struggled to accept homosexuality but sexual orientation was finally included in the anti-discrimination section of the Penal Code in 2006 and the law has permitted civil marriage between two people of the same sex since 2016. As popular and formal tolerance increases, queer relations are portrayed in poetry and prose, as in Beinir Bergsson's poetry collection Sólgarðurin (The sun garden) from 2021, which is an excellent example of this.

Dementia and illness are themes in novels such as Hinumegin er mars (On the other side of March), about a woman with dementia by Sólrún Michelsen (b. 1948) and Ikki fyrr enn tá ..., (2019, English: Not until …) about a husband's reaction to his wife's illness and death by Oddfríður M. Rasmussen (b. 1969).

Faroese crime fiction appeared in the 1980s and is mainly a male-dominated genre, with Jógvan Isaksen (b. 1950) behind by far the most publications. His exuberantly told detective stories depict crimes stemming from mainly international and (only occasionally) local origins. In recent years, Faroese literature has been enriched with migrants' descriptions of their existence in the Faroe Islands. The poetry collections Whisper of Butterfly Wings (FAROESE TITLE OR LANGUAGE SHE WROTE IN, 2020) by Kalpana Vijayavarathan and Ophav (Origin from 1996) by Ole Wich show how it only takes a few publications for a new trend in Faroese literature to emerge.

Formal modernism continues to characterize Faroese poetry. In terms of content, it has become less critical of language and, on the other hand, more personal. Lív Maria Róadóttir Jäger's (b. 1981) 2020 poetry collection Eg skrivi á vátt pappír (I’m writing on wet paper) deals with the poetic method based on the poet's own upbringing. Completely unique is the multi-disciplinary artist Trygvi Danielsen (b. 1991), who formally and aesthetically explores new, often humorous paths, lyrically as well as in prose, music and performance.

Further reading:

- Malan Marnersdóttir, Guðmundur Hálfdanarson, Ann-Sofie N. Gremaud, and Kirsten Thisted, Sovereignty, Constitutions and Natural Resources. In Kirsten Thisted and Ann-Sofie Gremaud (eds.), Denmark and the New North Atlantic (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 1st ed. vol 2., 2020), pp. 199-260.

- Malan Marnersdóttir, Henk van der Liet (ed.), and Astrid Surmatz (ed.), 'William Heinesens Det gode håb i lyset af post-kolonial teori' [W. Heinesen's novel The Good Hope in the light of post-colonial theory], TijdSchrift voor Skandinavistiek 25, 2 (2004), pp. 181-187.

Links:

List of works mentioned in this article

| Date published | Author | English title* (*indicates our translation/no official translation) | Faroese title |

| 1822 | The folk song about Sigurd Fafnersbane* | ||

| 1909 | Rasmus Rasmussen | The tower of Babel* | Bábelstornið |

| 1914 | J.H.O. Djurhuus | Poems* | Yrkingar |

| 1930 | Heðin Brús | Mirage* | Lognbrá |

| 1934 | William Heinesen | Windy dawn* | Was originally published in Danish: Blæsende Gry |

| 1935 | Heðin Brús | Firm grip* | Fastatøkur |

| 1938 | William Heinesen | Noatun* | Noatun |

| 1940 | Heðin Brús | The old Man and his Sons | Feðgar á ferð |

| 1946 | Martin Joensen | Fishermen* | Fiskimenn |

| 1952 | Martin Joensen | It's getting brighter on land* | Tað lýsir á landi |

| 1958 | Jens Pauli Heinesen | The poet from Selvík and his friends* | Yrkjarin úr Selvík og vinir hansara |

| 1963 | Guðrið Helmsdal Poulsen | Warm breeze* | Lýtt lot |

| 1970 | Dagmar Joensen-Næs | Rannvá* | Rannvá |

| 1971 | Jens Pauli Heinesen | The worm is called Fafner* | Frænir eitur ormurin |

| 1980 | Oddvør Johansen | Life’s summer* | Lívsin summar |

| 1985 | Rói Patursson | Likewise* | Líkasum |

| 1991 | Jóanes Nielsen | The wellington boots are the only pillars of worship we have in the Faroe Islands* | Gummistivlarnir er tær einastu tempulsúlur vit hava í Føroyum |

| 1996 | Ole Wich | Origin* | Was originally published in Danish: Ophav |

| 2005 | Jóanes Nielsen | Picture perfect* | Glansbílætasamlararnir |

| 2005 | Carl Jóhan Jensen | Tales of devilry* | Ó-, søgur um djevulskap |

| 2006 | Bergtóra Hanusardóttir | The Faroese* | Burtur |

| 2011 | Silvia Hendriksdóttir | Tell me you lie* | Was originally published in Danish: Sig at du lyver |

| 2011 | Jóanes Nielsen | The Brahmadells | Brahmadellarnir |

| 2012 | Jens Pauli Heinesen | Travelling into an infinite story* | Á ferð inn í eina óendaliga søgu |

| 2013 | Sólrún Michelsen | On the other side of March* | Hinumegin mars |

| 2015 | Kim Simonsen | December morning* | Desembermorgun |

| 2019 | Oddfríður M. Rasmussen | Not until …* | Ikki fyrr enn … |

| 2020 | Marjun Syderbø Kjelnæs | As a sprout* | Sum rótskot |

| 2020 | Kalpana Vijayavarathan | Whisper of Butterfly Wings | Published in English. |

| 2020 | Lív Maria Róadóttir Jäger | I’m writing on wet paper* | Eg skrivi á vátt pappír |

| 2021 | Beinir Bergsson | The sun garden* | Sólgarðurin |