Finnish Jewish intermarriage since 1917: intertwining religions and cultures

International research has highlighted intermarriage as a key issue for Jewish communities and other minorities globally, particularly as it is clear that intermarriage is perhaps one of the most apparent means of boundary-crossing between a minority group and general society. Research into intermarriage in Jewish congregations in Helsinki since 1917 reveals an interplay between an adherence to historic and religious rules and traditions, on the one side, and innovation and openness to incorporate new ways of doing things, on the other. It can therefore help to understand the challenges and changes that minorities face in Finland and elsewhere, as well as to illuminate contemporary religious outlooks in Scandinavia.

Finnish Jewish history prior to independence

Finland is often regarded as being on the periphery of Jewish life, yet, in fact, it has its own vibrant Jewish communities, with an interesting history and contemporary life. Currently, there are nearly 1500 registered members in the two Jewish communities in Helsinki and Turku. As Finland was part of the Swedish Kingdom, and later the Russian Empire, the history relating to the Jewish population and immigrants is often bound up with the laws of Sweden and Russia. Jewish settlement started in Finland during the times of the Swedish Kingdom (from approx. 1150 to 1809). However, from about the late 17th century, there was a prerequisite that Jewish immigrants had to convert to Evangelical Lutheranism, which was the official state religion of the country during that time.

Finland became part of the Russian Empire in 1809 and the majority of Jews that arrived in Finland during this period were from Litvak (with Lithuanian Jewish backgrounds). The traditions and the communities they established primarily upheld the customs of these roots. Tsar Nicholas I established the Cantonist school system for military education, bringing significant changes to the country’s history – not least from the Jewish perspective. Young Jewish boys were torn away from their parents and families and were educated in Russian schools and obliged to join the Orthodox Church. The Cantonist system was abolished in the 1850s, but the statute of 1858 allowed the boys who had been relocated to Finland under the system and their families to stay in Finland. The occupations open to Jews who lived in Finland at the time were limited to dealing in clothing and handcraft materials in the marketplace.

Rights and interfaith marriage after independence in 1917

Finnish Jews first gained the right to become Finnish citizens in 1917, when Finland became independent from Russia. The same year, the Civil Marriage Act (CMA) was passed by the Finnish Parliament which gave Jewish people the right to marry non-Jewish citizens for the first time without either spouse having to convert. The introduction of interfaith marriages inevitably led to the question of what faith the children of such marriages would be. Shortly after the Civil Marriage Act took effect, the Freedom of Religion Act (FRA) was implemented. It not only granted the right to practice religion in private and public, but also set out that a child belonged to the religious community of his/her father, unless the parents agreed otherwise.

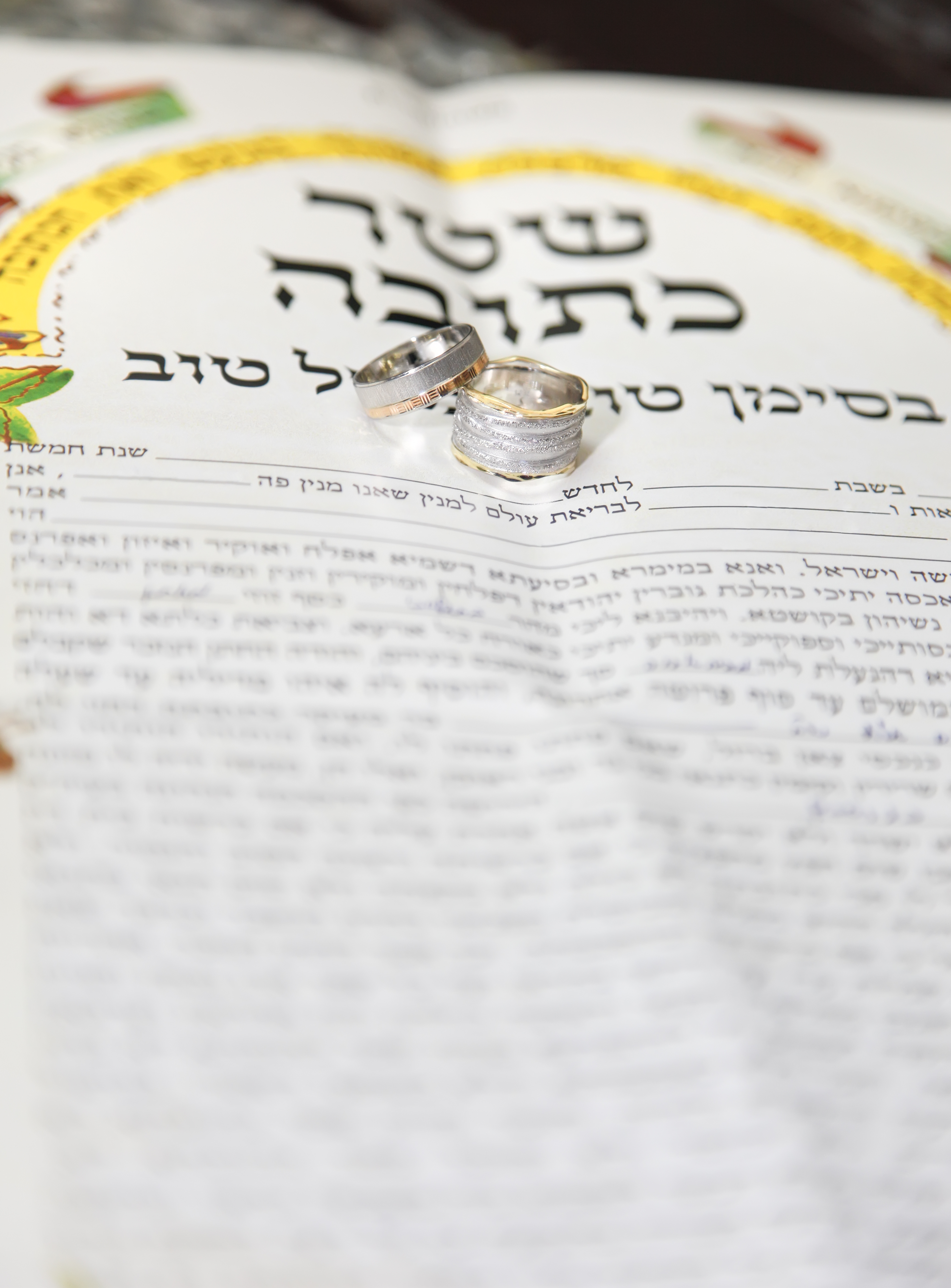

PICTURE: A letter in Yiddish from 1874 that discusses the issue of matchmaking. Source: National Archives of Finland, Finnish Jewish Archives, Archives of the Jewish Community of Helsinki.

Finnish Jewish congregations at the time understandably wanted to follow the regulations of the Orthodox Jewish law (halakhah), according to which a person whose mother is Jewish, or who has converted to Judaism, can be considered a Jew. The new Freedom of Religion Act was not in line with this which created paradoxical situations, and bureaucratic issues in Jewish communities. For example, certain children in Helsinki were to be registered as members of the Jewish community according to Finnish law, yet they were not considered Jewish by the Jewish law, because their mothers were not considered Jewish. To solve this sort of problem, the Jewish community of Helsinki, after consulting with a variety of rabbinical authorities (such as the Nordic Rabbinical Council), started the practice of childhood conversions of halakhically non-Jewish children. The parents of the children were to sign a written agreement in which they decided upon the Jewish upbringing of their child, and agreed to his/her childhood conversion, which took place before the coming of age ceremony (bar mitzvah, bat mitzvah) of the child at the latest. Interestingly, however, the non-Jewish mother of the child was not required to go through the conversion process. Children with one Jewish parent were, therefore, admitted to the congregation but were not considered formally Jewish until they underwent the conversion process. This 'tradition' has remained in practice from when the initial practice started in the 1950s and is still the valid protocol of Helsinki’s congregation. In case of male children – Jewish according to halachah or not – circumcision was a requirement of admission up until March 2018.

The 1922 Freedom of Religion Act was only changed in 1969 when it was actually reversed: from 1970, the child followed the mother’s religion unless the parents agreed otherwise. The law was revised again in 2003 from which date the child’s religion was decided on by both parents together until the child reached 12 years of age, after which the decision was based on the common view of both the parents and child. This remains legally the case today.

The first “organized” rabbinical court in Helsinki and the interdependency of intermarriage and conversions

Conversion to Judaism is complicated and a matter which is often debated. It entails a shift in one’s habits, as the person who is to convert is required to live according to Jewish law. After a long process of learning, the person who wishes to convert discusses his conversion with a bet din (a rabbinical court) that evaluates his/her readiness. If the rabbinical court deems him/her to be ready, the person must undergo circumcision (if it is a man) and be immersed in the ritual bath. Women are only required to be immersed in the ritual bath. In the spring of 1977, the first bet din (rabbinical court) in the Jewish Community of Helsinki, which consisted of three rabbis, was organized. In addition to the rabbi of the congregation at the time, the Hungarian Mordechai Lanxner and two Canadian rabbis were invited in order to provide the opportunity for adult congregants (who were mainly women) and their children to convert to Judaism with a locally-organized rabbinical court. The high number of intermarriages within the congregation may have been one of the primary reasons for this court being organized. Subsequently, similar courts have become common in the Jewish community of Helsinki, making the issue of Finnish-Jewish intermarriages and conversions very much interdependent.

In the beginning, Jewish members who chose to marry non-Jews, and newly converted congregants who were married to Jews, were both often discriminated against, and both have spoken about the hostility they experienced as members of the congregation. (For more information, see my article from Scandinavian Jewish Studies, or René Nyberg’s 2015 book ‘Viimeinen juna Moskovaan’ [The last train to Moscow], or Rony Smolar’s 2003 book ‘Setä Stiller Valpon ja Gestapon välissä’ [Uncle Stiller between Valpo and the Gestapo] (the latter two are only in Finnish)). As the rabbis changed over the decades, the conversion processes practiced often varied, as did the approach to conversions done outside Finland.

The synagogue in Turku. The synagogue was built on a piece of land donated by the city of Turku in 1900. Photo: Maarit Mannila, 2013. Museiverket. CC BY 4.0.

Today, the Finnish Jewish communities are truly diverse, with members from a variety of national and religious backgrounds. The earlier established Litvak traditions have sometimes been changed and contested over the years, as well as the identity and the practices of the members themselves. As a consequence, the following are key points of interest which can frame the study of local religious practices:

- The mixture of Jews from not only Askhenazi but Sephardi or Mizrahi ancestry;

- The tendency to view Judaism as a non-binary identity with complexities;

- The consideration of the social, cultural and religious boundaries the members of the congregations establish.

What can studying Jewish intermarriages in Finland tell us?

Jewish practices generally do not support the idea of intermarriage; marriage and intermarriage do not only provide companionship, but are the foundation of reproduction which inevitably underpins the demographic fabric of the Jewish community. This way of thinking is partially connected to the preservation of the Jewish continuity, as well as the Jewish identity of the individuals involved. While in the past, the separation of Jews and non-Jews was often legally enforced, today, in a globalized world, there is not necessarily such separation or segregation. Jewish practices and perceptions of Jewishness are complex, ambiguous, and creative, and highly dependent on the context and the surroundings.

Why do people intermarry in the Jewish community, and what happens after their marriage? Naturally, the small size of the Jewish marriage market may be one answer to the question, but more research is necessary. However, it is clear that intermarriage is perhaps one of the most apparent means of boundary-crossing between a minority group and the general society. The phenomenon of intermarriage is connected to the private practices of the individuals concerned, but may also have an effect on their religious communities. Intermarriages often generate situations in which individuals attempt to respect practices of the past, but are also urged to re-evaluate them. This is often influenced by practices of other religious or cultural traditions that may come from the surrounding majority society. Research to date has shown that members of the Helsinki and Turku congregations who have married a non-Jewish person strive to maintain a good relationship with their families and their spouses, but also attempt to maintain a balance between traditions that they find meaningful or necessary themselves. Their main aim for doing so is rooted in a variety of considerations: they find it essential to preserve their and their children’s Jewish identity and in this way to differentiate themselves from the surrounding society. They are flexible with rules of Jewish law that are connected to domestic spaces (such as their own family lives) but often comply with the regulations of their congregations.

Nevertheless, these marital choices do affect congregational policies, and even their religious traditions, often resulting in gradual changes or at least a level of flexibility in the prevailing status quo. Perhaps the most apparent signs of these gradual changes are: the conditional acceptance of (halakhically speaking) non-Jewish children to the congregation and the Jewish school; the establishment of regular childhood conversion practices; and allowing non-Jewish mothers of children who have patrilineal ancestry not to convert to Judaism.

The prism of intermarriages for researching vernacular Judaism in Finland, therefore, does not only allow for studying individuals and their (Jewish) family lives, but also provides the possibility of studying Finnish Jewry from a broader perspective; a perspective, that may facilitate the understanding of the challenges and changes that minorities face in Finnish society generally, as well as elsewhere.

Further reading:

- D. Pataricza, 'Challahpulla: where two wor(l)ds meet.' Nordisk judaistik/Scandinavian Jewish Studies, 30, 1 (2019) pp. 75-90.

- M.V. Czimbalmos & D. Pataricza, 'Boundaries of Jewish Identities in Contemporary Finland.' Nordisk judaistik/Scandinavian Jewish Studies, 30, 1 (2019) pp. 1-7.

- M.V. Czimbalmos, 'Laws, doctrines and practice: a study of intermarriages and the ways they challenged the Jewish Community of Helsinki from 1930 to 1970.' Nordisk judaistik/Scandinavian Jewish Studies, 30, 1 (2019) pp. 35-54. <br/>

- M.V. Czimbalmos, '“Everyone does Jewish in their own way." Vernacular Practices of Intermarried Finnish Jewish Women.' Approaching Religion. (2020 forthcoming)

- R. Illman, Researching vernacular Judaism: reflections on theory and method. Nordisk judaistik/Scandinavian Jewish Studies, 30, 1 (2019) pp. 91-108.

- S. Muir & R. Tuori, ‘"The Golden Chain of Pious Rabbis": the origin and development of Finnish Jewish Orthodoxy.' Nordisk judaistik/Scandinavian Jewish Studies, 30, 1 (2019) pp. 8-34.

Links:

- The author is a member of the research team of Boundaries of Jewish Identities in Contemporary Finland or “Minhag Finland” project.